* Chaminade graduate Ron Hemelgarn owned the car Buddy Lazier drove to victory in 1996.

* The Stoddard-Dayton paced the first Indianapolis 500 in 1911.

* New Lebanon's Harlan Fengler served as the chief steward for parts of three decades.

* Troy's Jack Hewitt, who at age 46, became the oldest rookie to qualify for the Indy 500 in 1998.

* Dayton's Salt Walther survived one of the most spectacular accidents in Indianapolis 500 history in 1973 and returned to drive the next year despite still suffering from his burns.

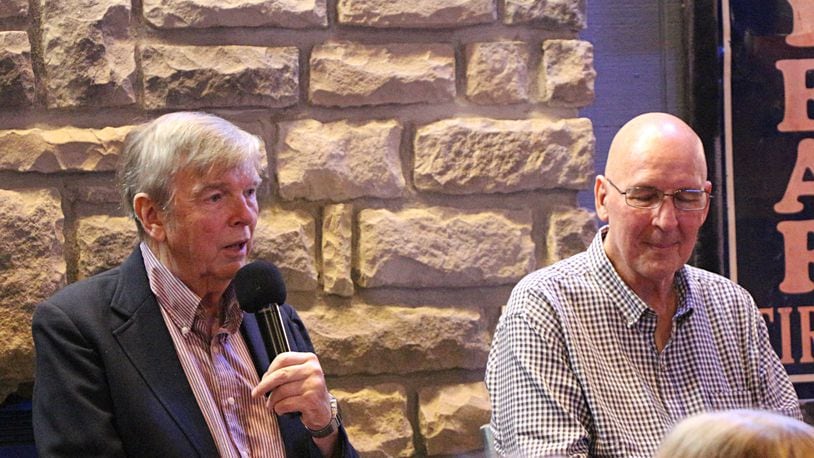

Indianapolis Motor Speedway historian Donald Davidson stopped by the Dayton Auto Race Fan club's monthly meeting earlier this week to share his memories of the Indianapolis 500 and participate in a question-and-answer session on the Greatest Spectacle in Racing. Davidson discussed a variety of topics including:

Walther, who survived a fiery 11-car pileup at the start of the 1973 Indianapolis 500. Walther, who battled an addiction to pain killers after his accident, died in 2012:

“I'll tell you what, Salt had a lot of detractors. I thought he was a good guy. People didn't like him for a variety of reasons, but to me he was one of the most charismatic human beings I think I've ever met. Just a really good person. … He met a sad end but one of the most charismatic men I've ever met.”

Fengler, the tough-as-nails chief steward at the Indianapolis 500 from 1958-74:

“He was not the most popular person at the track. He probably was his own worst enemy in that respect. But Harlan Fengler should get a lot of credit. He actually was a driver and he did drive in one 500. That wasn't his greatest day. But he actually won four track championships and he was a riding mechanic. When Harry Hartz finished second in 1922, Harlan Fengler was his riding mechanic.

“He built a couple of cars. He was an engineer. … He was involved with the movie industry a little bit. … When he moved to California he actually was friends with Loretta Young. … He ended up here, worked for Ford and was the chief steward for so many years. He was very strong willed and very opinionated. It came over in such a way he was not warm toward the press and also the public. Unfortunately, once it became the thing to get on Harlan Fengler he couldn't win. It's too bad because he was a very intelligent man and had this amazing experience. You kind of took it for granted. But if you wanted to know about Leon Duray or Frank Lockhart or Jimmy Murphy, Harlan Fengler knew them. He was somebody that could give you more than just the stats. If you wanted to know the character he could give you a picture of what they were like.”

His views on the best driver never to win the Indy 500:

“For many years the no-brainers were Rex Mays and Ted Horn. Since then I think you would consider Jack McGrath, Lloyd Ruby, Michael Andretti and I think Roberto Guerrero and Scott Goodyear. I know in 2011 there was an attempt to name the 33 greatest drivers in the 500. We had a panel of about 150 people, all experts at some level. … I was thrilled with the responses that came back because they named the drivers from the early days. … I would say Lloyd Ruby was so highly rated by the other drivers. In fact, Johnny Foyt said in the years he was at the track that Lloyd Ruby handled the Indianapolis Motor Speedway better than anybody.”

Dayton's radio affiliation with the Indianapolis 500:

“This really surprised me. When the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Radio Network was formed in 1952 there were 26 stations and one of them was WING in Dayton. And until not too long ago it still carried on the radio network. I thought that was remarkable that it was the same radio station and the same call letters. I was dismayed to learn not too long ago that WING no longer carries it and the radio network is not available through a Dayton station. I guess as Jerry Seinfield would say, 'What the hell is going on?' Dayton doesn't have a radio station that carries the broadcast.”

The challenges of covering the Indianapolis 500 in the early years, namely the lack of interstates and the use of manual typewriters:

“The coverage in Dayton was fantastic. And in those days they didn't have press conferences. If you wanted to get interviews with drivers you didn't sit in a press room. If you wanted interviews you had to get them. It just amazed me the coverage in the Dayton Daily News in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s was fantastic. … They would have to drive over to Indianapolis on (U.S. Route) 40, and they would probably have on a suit with a hat and a tie, find the people to get interviews and drive back to Dayton and write the stories on a manual typewriter. Isn't that amazing they would go to the trouble to cover an event that not only wasn't in their town, but wasn't in their state. By golly, hats off to all of the newspaper reports from the Dayton Daily News for all of those years.”

The story of famous World World II pilot Jimmy Doolittle, who led 16 B-25 bombers on a raid over Japan on April 18, 1942:

It was 1931 and driver Dave Evans his riding mechanic noticed the water temperature was climbing. They gave hand signals to the pits, but there was no response. The hand signals grew more animated the next two and three laps.

Still no response.

“They looked at each other and said, 'Okay we'll just run it until it blows up,'” Donaldson said.

Evans finished the race, albeit 38 minutes after race winner Louis Schneider, and found the person in the pits responsible for the hand signals. When asked what happened, the pit member said “Well, I couldn't find the piece of paper that had the (hand signal) key on it.” Doolittle then loosened the belt on his coat and the paper fell out.

About the Author