I have been in this role as Community Impact Editor since September of 2021. I’ve hosted many different panel discussions, both virtual and in-person, and none of them, in my estimation, have come close to the power of the candid discussion held with these three phenomenally gifted photographers.

I don’t want to appear self-congratulatory. Indeed, the key difference with this discussion is my absence. Getting out of the way and allowing Imani, Shon and Sean discuss what was important to them eclipsed any line of questioning I could have come up with as a moderator. We had scheduled time for a 20-minute discussion — it lasted nearly an hour.

The conversation touches on their creative influences, their approach to their art, and the challenges they face as photographers, business-people, and residents of Dayton. It was honest, open and did not shy away from difficult topics.

The experience with this discussion solidified something I have suspected since I assumed this role: Ideas & Voices reaches its fullest potential when it hands its platform over to those in our community willing to speak openly and honestly about their experience.

Today’s Ideas & Voices features that discussion, along with work from each photographer. I cannot stress enough, however, the importance of watching the recording of the full conversation available below and exploring more on daytondailynews.com/black-history, where you can find other Black History Month coverage and contributors to February’s 28 Days of Black Excellence project.

MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS

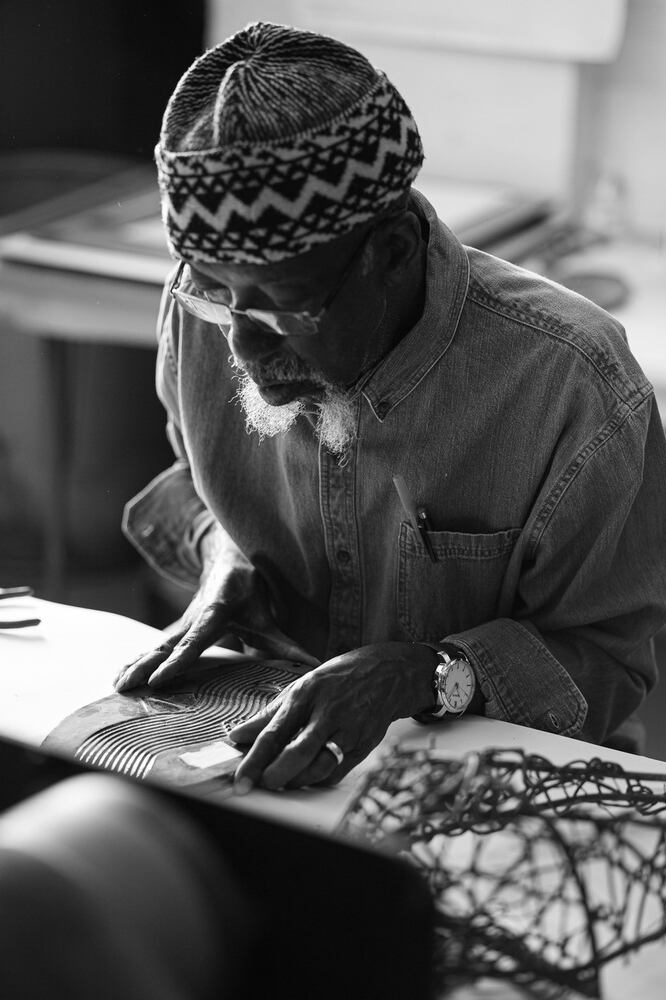

Shon Curtis: Born and raised in Dayton, Shon Curtis is a freelance photographer for various agencies and organizations, including OMS Photo (Cincinnati). Learn more about his work at shoncurtis.com. (Instagram: @iamshoncurtis)

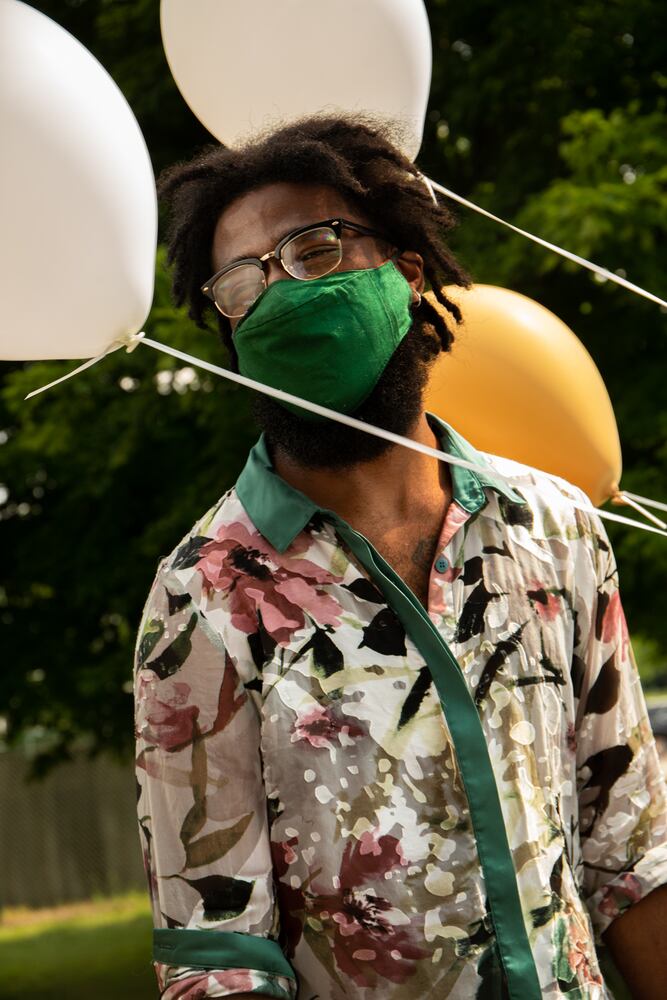

Sean Korey: Sean Korey is a creative with a diverse range of pursuits in the arts, including photography, poetry, visual curation and conceptual art. You can learn more about his work at seankorey.com. (Instagram: @Sean.kxrey)

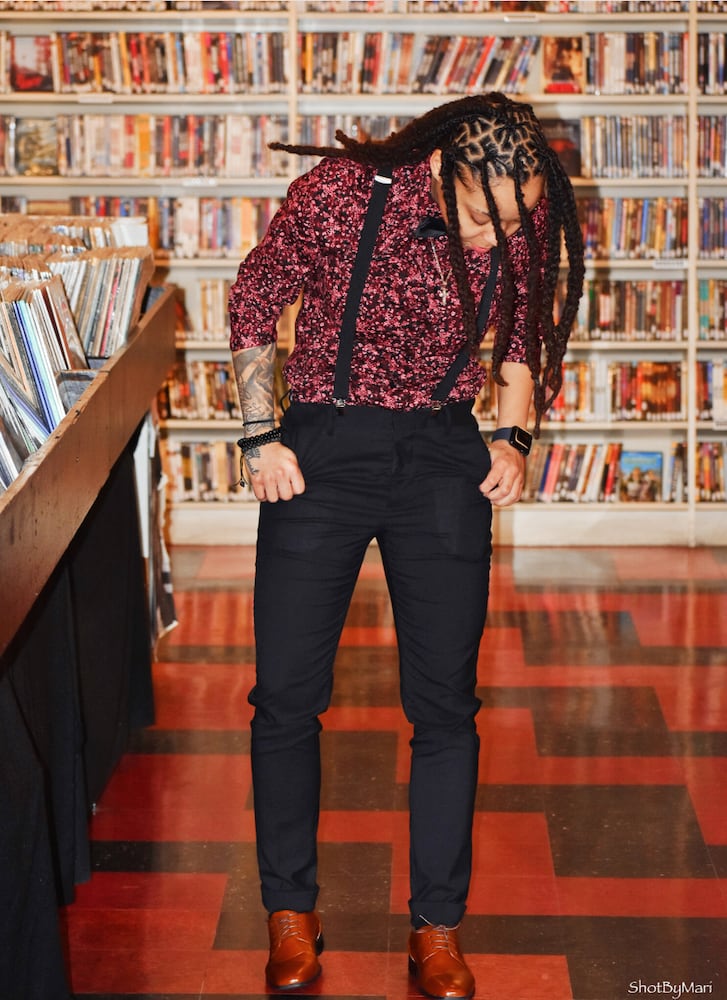

Imani Mari: Originally from Las Vegas, NV, Imani currently lives in Dayton. She has been a photographer for four years and owns her own photography business. She is always looking to learn, expand, build connections, and grow within the field of photography. You can learn more about her work at imanimariphotography.com. (Instagram: @ShotBymari)

WATCH THE FULL DISCUSSION

READ THE TRANSCRIPT

Note: The transcript below has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Curtis: I am Shon Curtis, or, as my born name is Shon Curtis Houston, Curtis was important to me because it was my grandfather’s last name and I thought that was important to my legacy. I’m a photographer, been a photographer for about seven years, going on eight years now. Before that I was a teacher. I think that my other art mediums, like spoken word and music, all play into what gave me breath as a photographer and gave me legs as a photographer, because it helped me tell stories.

Mari: And that’s really interesting that you were a teacher. I didn’t know that.

Curtis: Yeah, that was my background for like seven years before that. I taught adults with mental disabilities.

Mari: I work closely in that field as well.

Korey: That’s something we all have in common. For a year of college, I was studying rehabilitation services.

Curtis: I didn’t know we had that in common.

Mari: I’m actually a case manager supervisor now. We do our work behind the camera and in the community.

Curtis: That’s kind of a wild realization. All right, what else we got? I want to hear more. Who are you, Sean?

Korey: I’m Sean Korey. I’ve been doing photography seriously for about four or five years. As a hobby for much, much longer than that. My uncle, he was a professional photographer for a local newspaper in Huntsville, Alabama. And he traveled the world with photography. And that’s kind of how I got interested in photography. He passed as a suicide and that kind of kind of made me pick up the camera again and take it more seriously. And that’s why I say I’ve been doing photography seriously for about four to five years. I am like you, Shon, I am a multidisciplinary creative. I do poetry. I draw, I act, actually went to school for theater studies. And yeah, I have a book that I wrote. So I’m also a self published author. It’s a poetry book called QUID EST VERITAS, or What is truth? And that kind of journeyed my “Yeshua years” is what I call them. So when I turned 30 I started contemplating religion, life for myself outside of structured religion, and the poems are kind of like that journey through that process.

Mari: So important to unlearn and relearn.

Curtis: Yes. If that’s not the Black educational experience, I don’t know what is.

Mari: A lot of unhealthy traditions that we need to break. And bring more light to mental health and things like that, things we don’t get to talk about.

Curtis: Absolutely.

Mari: My name is Imani. I’ve been a photographer for about four to five years now, seriously, as Sean said. I’ve always been visual. I always, you know, took pictures of my food, took pictures of my friends, just always have been the one with the camera in my hand, even if it was on my phone. Originally, I’m from Las Vegas, Nevada, and I came here to pursue school. I ended up getting my master’s at Wright State University, my bachelor’s from Central State University. I decided not to leave the area and to pursue art and take it further.

Curtis: There’s a very distinct line of synergy between us. Which is another reason why I’m like ‘why has this has not happened before?’ I’m even more grateful that is now. I would love to hear your ‘Why.’ Like, why are you a photographer? Why have you chosen this career as an image-maker?

Korey: My ‘Why’ is really humanity. That’s the biggest focus of my photography. I’m actually working on a project now, it’ll be my first actual project. Instead of doing things for everybody else, doing it for me. Humanity has been the driving force. There’s this quote that I love. Maya Angelou is the one that I heard say it, but it came from the first Black Greek playwright, Terence, and it’s Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto,” or “I am a man, I consider nothing that is human alien to me.” And it was one of those things that when I first heard it, it made me think so deeply about the human condition, and circumstances, because we all fall into different circumstances. And once I contemplated that I wanted to discover or see that in other people, and I think being behind the lens, for me, was the most comfortable way for myself, and for my subject, to really view humanity. Because I think, if I can make somebody feel comfortable in front of my lens, then I can actually see who they are. And the greatest part of photography for me is capturing the lens, but actually going through my edits and looking at those moments. I love catching candids. I hate posed photos. I love catching candids, and I love studying those candids and seeing the real person and seeing the humanity.

Mari: I can definitely piggyback off of that, as far getting that moment that is not posed, that’s authentic. People being themselves, those are the most important photos. And the reason why I am in photography is because photos are the last thing we have left. That’s all we have from history. That’s all we have our grandmothers, our grandparents, those little photos that are all raggedy now. I just want to be a part of that history, to be able to create more quality photos for families and for people.

Curtis: Absolutely. My reason why is not too dissimilar than yours, honestly. So my reason why is the truth, right? It is this way I use to document my reality and to document the people in front of me and their reality and to tell and to articulate their stories. I feel like every photo that I take has to be the truth, otherwise, I’m doing a disservice. And I think that a lot of this gift that we have is meant to be in service of something. That’s the role of the artist, to constantly evolve, but to also constantly give, and to tell and to articulate something, whatever it is, whatever you’re deciding to tell. Whether it is people, products, whatever it is, we are dedicated to being honest and telling the truth and holding up this mirror for the world. For me, it’s James Baldwin and Toni Morrison and John Coltrane. Those are my three that hold me together. There’s a quote by Baldwin where he talks about the role and responsibilities of being an artist and how you need to be that witness for this very dark place. Because so many people are just trying to find the light that they don’t even understand the depths of the dark, right, they just get lost in it. It’s our duty not to be lost. It’s our duty to tell what is really there, just to help the next person navigate. For me, that’s all photography is for me right now in this medium and this form, it is that dedication to having to tell the truth and having something to say and having to lend a torch or a flame so that others can see it. Toni Morrison wrote James Baldwin’s eulogy for The New York Times. And she quotes somebody, I think she quoted Hawthorne, where they talked about this kindling, and this little flame that’s necessary for us to keep going and lead this path for people to see. And for me again, that’s all we do is we share that flame. That’s each photo. Which is a deeper construction of what light is to photography, right? The light is just as important as the camera, or the photographer, if not more so.

Korey: The camera doesn’t work without light.

Curtis: Facts. Right. So we have a similar reason why, which I think is why our work exists in the same place a lot of times, because our names are in the same place a lot of times.

Mari: We’ve all probably gotten the comment of “you have an eye for this.” I mean, there’s some stuff that we have to learn, you have to learn lighting and things like that, but for the most part, it’s a gift. It’s something that kind of came naturally to us. And that’s something that we have to appreciate and kind of dominate. We can really dominate in this field, just because we have a natural gift and a natural talent for it.

Korey: I agree. I think beyond that, it’s people notice when your work is authentic, and when your work is coming from a sincere place. It’s crazy that people may not even understand lighting, but know that a certain photograph has more meaning than another one, somebody just snapping the camera and not having ever learned lighting. Even without learning about lighting, I was applying lighting techniques.

Mari: What have been some challenges you guys have faced in this profession?

Curtis: A lot of my work, presently, is very commercial, it’s very brand-oriented. And oftentimes we don’t get the same appreciation, the same bidding, which is the money for the job. We get left out of the conversation a lot. It’s in every industry, it’s not just photography. And it’s interesting, because a lot of my a lot of my colleagues and my contemporaries are non-Black photographers, right? I’m a part of a commercial studio in Cincinnati, called OMS, who is almost exclusively white photographers. I’m the Black freelancer on the roster. And it’s not to say they’re not hiring Black photographers or not contracting Black photographers, or have any issue in that social element at all. It’s to say that we don’t even know that we can approach a commercial studio and say, “Here’s my portfolio, here’s the work I do. Do you deem it good enough to be in front of your clients?” And because I did that, they were like, “Absolutely.” And the thing is, they’ve been looking for my type of voice. Not even just the Black voice, but they’ve been looking for a voice that’s not theirs. Because oftentimes, in this very specific industry, in commercial photography, you get a lot of same approach and the same lighting techniques and the same style in terms of how to light Black skin or for any person of color. Which is a different approach, right? Different than, say, a Black photographer coming in and saying, “Okay, this is how I would light myself, this is how I would light my mother, my father, my cousins.” And then they see that and they’re like, “Whoa, this is completely different.” I’m like, “Yeah, well, this is my experience.” I’ve experienced not being lit properly, not being color corrected properly, given this orange sheen on my skin, or being the brightest thing in the room. I have darker skin. So you’re going to light me some kind of crazy way while everyone else has this beautiful, nuanced lighting. You have to figure out how to walk that nuance into your art and into your medium, which takes more time to learn the discipline. But that helps us stand apart from everybody else. Just the most basic differences that I seem to face when coming into a room as a Black photographer come from the same differences I face just being a Black man. That, “Oh, his work can’t quite be that good.” But then when it is that good, it stands out, because they’re like, “Oh, my God, I didn’t know that you create something like that.” Yeah, well, you give us opportunity, we can do a lot of things.

Mari: Representation is important. It has to be important. And like you said, a lot of people are fearful to do that footwork and to walk into places. To give your portfolio and say, “Hey, I do this.” Just because we already have this stigma, that they’re going to say no, or they’re going to look down on my work because I am Black. We have to break that within ourselves and get out here and do that footwork and walk into these restaurants, like, “Hey, can I hang my piece in here? Are you guys interested in purchasing pieces?” The little things that we are very much capable of, but we lack the drive to go and get it.

Curtis: The first four years of doing this full time were a nightmare. It was learning. I didn’t go to school for it. I tried to go to school for it. It was great until I was way ahead of the classes and they were like “we’re taking your money.” So coming into my fourth year, I realized that I have to be audacious. I have to have the audacity to do things that other people won’t do and be fearless now. Not to be arrogant, but just to make sure my voice is heard in the room. Because for me to say that I’m good enough wasn’t enough, right? My work had to speak. It had to say it for me. And I just had to be audacious enough to step into that room with the work. To say, “Yeah, this is my piece. This is what I did.” That’s the switch that flipped for me. Being patient. Owning our narrative.

Mari: What about you, Sean? What do you struggle with?

Korey: There’s a few challenges that I can identify. One would be time. Two would be self-appreciation or self -recognition. I say time, because I don’t do photography full-time, I have a full-time job at Wright-Patt as a facility engineer. So a lot of the times creating space for me to actually do photography, for me, is difficult. I do photography, I’m a visual director for Scripted In Black, and that’s almost full-time in itself, outside of what I actually do professionally for my clients. So finding the time to create the way I want to create is one of the biggest challenges for me. I’m also a father of four, with a wife. So creating that, I don’t want to say balance, because balance, you’d never find balance, because something is always throwing that off. And I say self-recognition because I do this as a hobby. Well, not anymore. Because I have treated this as a hobby. And now I’m walking into actually doing this professionally, taking on clients. Being a visual director, I had to realize that I am a creative. Up until three years ago, I didn’t view myself as a creative because I didn’t feel I dedicated enough time to my craft to be considered a creative. In these past few years, I’ve actually embraced my artistry, and in more than just photography.

Mari: And it’s important that we have that confidence in ourselves, because that’s when we’re low-balling people. And “I’ll just do it for $100, I’ll just do it for the $150.” Like, no, we really have to understand that we are creatives and we do have equipment. Our creative side can be limitless. And as far as the money we put into it, the time we put into it, just our art period is worth something and we have to start owning that and not being too humble, or to like, “You know, I just do this.” No, we are goddamn good at what we do look at where we’re at.

Korey: It’s almost false humility, because when you look at the definition of what being humble actually is, it’s walking in your full purpose. So in a lot of ways, when we say we’re being humble it’s false humility, and we’re not fulfilling our full purpose.

Mari: Humbleness is kind of just character. Are you doing right by people? Are you doing right by your business? Are you providing the qualities and the things that you said you’re going to provide? I think that the society has kind of misconstrued the word humble. And like you said, it’s just a false reality, really.

Curtis: I agree. I think about that often because I think about how I conduct myself as a business person, because there’s a distinction between being a photographer, being an artist and being a business person, right? There’s a line that you walk in each facet that really allows you to conduct yourself holistically. Me as the artist, I’m constantly on this mission of growth and I have to evolve and I have to experiment, and there’s never going to be a mastery on it. There’s going to be an attempt at a better understanding every time. Me as a photographer, this one medium that I’ve decided to stick with for long enough to call myself that and to make money as that is me understanding okay, there are these various realms of photography. And though my work is very studio and very commercial, very editorial, that’s an that’s a niche that I have to stay in or that I’m that I’m considered for. But then as a business person, now you have to look at finances, you have to check books, you have to know about hiring, 1099′s. You have to know how to navigate contracts. If you’re working, doing a freelance project for some company, they have lawyers that are attached to their contracts that give them these guidelines, and its verbiage is so that they’re covered. You’re not covered, you have to be educated enough, or know how to obtain what’s necessary or obtain the right information, so that your business is covered so that you’re not just showing up with your camera, no contract in hand, and then when it’s time to deliver images and then receive payment, you out, because you didn’t handle this business part. Or when taxes come and now you’re looking at all the things you bought for the year and you didn’t write anything off, you didn’t keep your receipts and your bookkeeper wasn’t proper. Now you’re out that way, too. There’s a management that has to come so that you can navigate all of this properly. And you can be humble and do these things. But you also have to know exactly where that falls into this bucket of other things that you’re trying to hold together. You know, one of the best things I learned was the my ability to say no, and my capacity for what no means. Because everybody wants to collab, everybody wants to do something with you. And you have something to offer, you have this thing that you can give that other people can’t do. But you have to learn to say no, sometimes because you can’t take every check, you can’t take every contract, you can’t take every job, even if it’s one that really hits your heart. Save it for later, if later come and have enough forgiveness and grace to say, you know, it’s okay that I said no this time. If they don’t come back, they don’t come back, it’s fine. Go and move on, there’ll be more, right. You have to learn that because so much of this is you learning these lessons, right? Every L you take is going to be a lesson that gets you to this next place. You got to let that brush, you got to let it go. Because there’s more work to do.

Mari: That’s important. And it’s weird that you brought up the taxes and the business aspect because honestly, that’s something that I struggle with. In my fourth year and taking my business more seriously as a business. Yeah, the LLC is cool, but then, what do I do next? How do I really maximize my business name? How do I make sure I’m doing everything properly? And I think that’s where education come in, workshops, doing that footwork to get out to see like, ‘Hey, can you help me with this?’ Or like, ‘Hey, is this something that you’ve you’ve experienced before? Would you be able to help me with this?’ Or just doing more research. So, for me, business is a struggle. And then being a full-time supervisor, doing this, just traveling, other things of that nature, life gets busy. And then at the end of the day, it’s just like, where did all the time go? And you wake up and do it all again, and ask the same question: where did the time go? So I think we have to learn to better manage our time. And like you said, it’s not going to be a perfect balance every time but we do have to manage things and maybe cut out certain days for certain things or certain times for certain things and really stick to that.

Curtis: No, I agree. Now, imagine doing all this, managing and balancing all this other stuff, and then throw in you’re Black on top of it all, right? Like that extra layer of context that gives that extra little layer of difficulty that comes from this Black experience. I want to show up with these hats on in this way. And then I have to also deal with this outside world who may not take me seriously just because they can’t identify with me. I might not be the businessman they’re looking for because I’m a young Black male who went to college but didn’t get the credentials necessary. Matter of fact, I mean, I will talk about all this, we’re talking about all of it. The building I’m in right now is The Hub, which is powered through the University of Dayton. Which is great, I love UD for what they do. But I was up for an adjunct position. Being a photographer, a studio practicing photographer, I don’t have a degree as a studio photographer, I went to school for English, and I ended up going to art school, but I didn’t finish the art program for photography. I was up for the position because of my experience of seven years being a working, professional photographer. And working for all these countless publications doing studio work primarily. I’m up for this job and I don’t get it, because it goes all the way up to the dean who basically said that because I don’t have a degree, all I have is experience, that wouldn’t qualify me enough or wouldn’t be equitable enough to, I’m assuming, the other professors, for me to come in without a degree and be a teacher. However, I still teach their students. I’m their artist-in-residence right now. So I’m still in their facility. I’m still teaching their kids. And they’re learning about studio photography from a person who does not have a degree in studio photography. But I do studio photography seven days out the week. So I know there’s a significant portion of it that comes from being Black in this space, which is not very Black, and not having this degree, but having all the experiences a degree qualifies as. Because a lot of professors aren’t working photographers. They are professors of education, which makes sense. But it’s a different ballgame when you’re actually out here doing.

Mari: It’s a different world for us. We can go to YouTube University, we could do anything that we want to do, we can do anything we want to do. And it’s important that we utilize these resources on the internet. It can be very useful getting to know these new social media outlets and stuff like that to kind of get our branding out there. And getting our name and who we are out.

Korey: The biggest asset we have is us. Shon knows that anytime I see him, I’m asking him about 1,000 questions, just because I love his work. And I’m always trying to learn. No matter how many people tell me how good I am, I’m never going to be at the point where I’m satisfied with my work as as far as not wanting to progress. And I think our biggest asset is each other. I even tried to learn from people that may not have as many years of experience as me. I use a Nikon, and this other photographer uses a Canon. I have no idea about the different ins and outs of Canon, but I can tell you about the Nikon and why I love the Nikon and the color that comes out of a Nikon.

Mari: I loooove the Nikon, right?

Curtis: I’m gonna let y’all have that, as a Canon shooter. When I started, I remember asking three local studios. And I am not about to put them out there like that. I asked three local studios to allow me to assist, allow me to sweep the floor, as I just wanted to work in a studio. I knew early on I wanted to do studio photography. I knew so many people did natural light, outdoors, which I thought was dope to learn. But I knew I needed to distinguish myself in a way, so I wanted to do studio. So I asked these people “Let me sweep your shop for free.” I just want to be in the space and learn, ask questions, have access to you, to talk to you. And they were all non-Black institutions. Not a Black person on the roster at all. And each one of them said no or they ignored me. I ended up writing them on LinkedIn, email and Instagram. All three of them said no or ignored me. So I came back, did my first big campaign for the City. One of them hit me up and said they loved what they saw, right? This is years after I had hit them up and got those no’s. Then I did another campaign. This time, it was kind of like a rival campaign for one of those institutions. And mind you, I’m not an institution, I’m by myself. Freelance. So for me to do one at that scale, for them to see it and to see has been published and put out into the world, and it’s now used in marketing for one of our local spots here. They hit me up and say, “Can we go to dinner? We’d love to talk to you.” I ignored it. I’m like, “No, I remember this energy you had, I’m gonna give you a little bit of that energy back.” But then I thought about it. And one time I was out for drinks and I ran into them, they tried to sit down with me, we had this long conversation, I got to address why they ignored me my first time out here. So all that said, I will always remember being treated that way. So whoever comes up to me and talk to me about photography, we’re going to talk extensively, everything I know, I want you to know. Whether it’s about business or being a photographer, or using a studio, I want to share whatever I can share with you, no matter how long you’ve been doing it, no matter if you’ve got more years than me. If we want to talk about pricing, I’m gonna talk about pricing. There is no topic off topic for me, when it comes to helping my community learning this.

Mari: You really mean that. Because the first time I think I met you what, a week and a half ago or two weeks ago, whenever you took those photos, and I brought up lighting and me wanting to know more, you were very arms-open, you are very inviting. And I felt like I really could call on you if I had a question. And it wouldn’t be any, you know, weird animosity, because Dayton does get weird when it comes to things like that and helping others and seeing other people win. That was a very memorable interaction I had with you.

Curtis: Thank you for that, seriously. We have to support each other. I can’t see you fail. I don’t want to fail, I don’t want you to fail. So we gonna hold each other and get up here.

Mari: You know, it’s just people you can’t ask any questions just because they’re gonna come with “Oh, here’s my $400 30-minute class.”

Curtis: People keep asking me if I’m going to do a class of some kind, and I think I will eventually. But it doesn’t mean I’m denying access to the information I have now. I’m going to make that something super specific if you wanted to learn this very particular thing. Because that’s the only way I can wrap my mind around making some kind of course on it. Because otherwise, I want you to just know what I know. It can be as valuable as it’s going to be to you, I just want you to know what I know, so that your job is a little bit easier. That you finding your answer is a lot simpler than how I had to find my answer. And also, I’m not afraid of asking questions. I’ll see a campaign and I know how to do the right research to get to the person who did it. So I’m in their DM or in their email or hitting the assistant up like, “Yo, can I get five minutes with this person? Can I get 10 minutes? Can I get five questions in your email that you might answer if you have the time?” I don’t care how big, does not matter to me. We want to find a way because that’s what we do. We are that resilient, that we will always find a way, even though we had to make it ourselves. So you always have access to me.

Korey: I think it’s funny that Imani had that experience a week ago. I had that exact same experience, what was it like two years ago when you did the panel for Scripted in Black? And honestly, the moment where I was able to ask Shon a question and he gave me more than what I even asked for, that made me want to go look into his photography. The interaction that I had with Shon made me want to go look into his work. And once I saw his work, like you say, you’re like in this niche of editorials and stuff like that. I see the truth in all of your work. That piece that you did with the postman, seeing the amount of time that you put behind getting the right lighting, but telling the story of finding a place that he frequents that nobody knows and things like that. That’s beautiful to me. The way that you act outside of being behind the lens shows behind the lens.

Curtis: I receive that. I really receive that. Thank you. Thank you, seriously. Man. Nobody’s said it like that. I appreciate that.

Mari: Outside of what we’re doing today, and I’m not just saying this, I think that we should at least talk maybe once every couple months or something. This was really nice. And I appreciate hearing different perspectives and just knowing that we’re literally within miles of each other, we can get together and have shoots or have one subject and do shooting competitions, just little things to keep it fun and light, you know. Yeah, I enjoyed this.

Curtis: 100%. I love hosting people in the studio. I love talking about lighting and approach. I think that’s the only thing that we really can talk about individually and teach about individually is our approach, because photography is always changing. So that’s the real thing that defines is our approach. I also just love being around artists. Even if I’m just putting on a record and having some wine and kicking it, I’m with that. I’m with that 100%.

Korey: I feel some some type of installment, kickback, workshop.

Curtis: I have a question for us, though. I know that we are working in and out of Dayton and a lot of times we get asked how can Dayton help support us and support what we do? Or support the artist community that we care about? I would love your take on that. Just in general, how can Dayton help support you, your community, what you care about?

Mari: That’s a tough one just because you put in what you get out. So I feel like even us three, how we kind of have our community-based jobs, I’m not sure what more Dayton could do. I think it’s what more can we do for Dayton to continue to be what has been there for us?

Korey: In the same vein, I don’t think I’ve done enough research for myself to know how Dayton can serve me because I haven’t fully researched how I can serve myself better as a photographer in Dayton. I think there’s something within the community because I’m detached from other photographers, really, unless I randomly meet them at an event or I see somebody shooting something. So I think creating community within ourselves will help me at least understand how the community can serve us.

Curtis: Facts. I have a an interesting critique of Dayton that I may have to think deeper on because I want it to be a full critique and not something limited. There’s this significant performance in Dayton where the things that matter don’t really matter at the end of the day. And I think as artists we have a really interesting perspective on that conversation. We have an interesting perspective on what it is to hold a mirror up that shows an image that has to be critiqued. And I think that for Dayton, we’re not necessarily fearful, we’re apprehensive of showing that mirror when it doesn’t affect us personally. But as one of those people that has to tell the truth about our community and about the community of Dayton as a whole, I tend to like to hold that mirror up and just let whoever’s in front of it live in it and understand it. In terms of art in Dayton, I think we need more real conversations like this. I think there’s still a lot of gatekeeping that happens when it comes to who makes it into the art world and who doesn’t, whose voice goes beyond the walls of the Gem City and whose don’t, whose voice matters whose work is in front. These things are always happening, even as a person whose work is in front. Sometimes I’m like, “Such and such should have got that gig. It makes no sense. They’re more than qualified.” I think that, but is there a space to say that often if you’re not sitting on some kind of board, or have some kind of voice that is upstanding enough to matter to the people that write the check or the people that go and get their little glass reward printed and stamped and given in a ceremony? I think that there are too many moments like that that are inauthentic, which is why a lot of the artists don’t often participate in it — because they don’t feel welcomed. I would love to see someone come in and fix that. But I love this place. I do, I love this place. Born and raised here. It’s in my heart, it’s in my blood. And I know that me living here is why I’m an artist. So wherever I go, I know that was because I was here.

Korey: Your perspective is is a lot different from me and Imani because both of us are not Dayton natives. So that makes a lot of sense that we express the way that we express as far as not knowing and you could pinpoint exactly what the city needs because you were born and raised here. So that says a lot about you and and how you view your city and the love that you have for your city to want it to grow. I’m just glad that I could potentially be a part of it.

About the Author