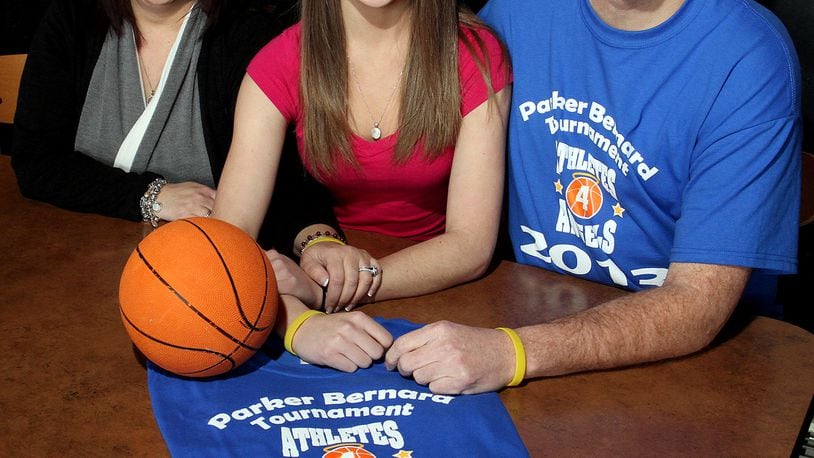

Tonight, she, her husband Scott, their 18-year-old daughter Peyton and many of Parker’s school friends, family members and fellow hoops players in the area basketball fraternity he was so much a part of will get some glimmer.

It will come when Chester Golson – minus one leg, but with a brand new kidney and some renewed zip in his step – walks onto the court at Bellbrook Middle School and tosses up the ball for the ceremonial opening tip of the second annual Parker Bernard Basketball Tournament, a three-day, three-gym event involving 54 third- to seventh-grade teams from across southwest and central Ohio.

The 54-year-old Golson is alive thanks to Parker’s donated kidney.

“The gift Parker’s family gave changed the quality of our life – really, it saved Chester’s life,” said Golson’s wife, Sharri. “We are so thankful to the Bernards. We love them for that.”

And at about the same time as the tournament tips off in Bellbrook, Patti Vantilburg will be leaving her job as an office manager in East Liverpool and heading home. The 49-year old mother of two feels the same about Parker and his family as do the Golsons.

She received part of the young boy’s liver. “I feel like a brand new person,” she said. “I think about the Bernards every day. I think about Parker every day. My kids do, too. So does my husband. I owe my entire life to that family.”

Around the Midwest several other people also are benefiting from Parker’s gift of life. According to Life Connection of Ohio — the nonprofit agency that administers organ donation around here — a 4-year-old girl got the other part of Parker’s liver, a 48-year-old woman with three children got his heart, a 41-year-old man got his pancreas, a 64-year-old woman with grandkids got his other kidney and a little boy just a few months old got his corneas.

The father of that child recently sent the Bernards a note that said:

“I want to tell you my baby boy (now 1 year old) is so happy with his new eyes. He can watch TV, play toys (sic) and play with his elder sister. All of these is not possible without the precious gift from your child. Again a million thanks for that. May Jesus be with you always.

“A grateful recipient’s dad.”

A shining life

This is the first season in a long time that Scott Bernard has not been a regular at Dayton Flyers home games.

He has season tickets in the Coach’s Corner – Section 103, a few rows behind the UD bench – and that’s where he and Parker sat every game … until 13 months ago. Now the experience just isn’t the same for him.

A sixth-grader at Bellbrook Middle School, Parker was a huge Flyers fan. His bedroom — from the blue curtains to the framed programs of games he attended with his dad and the banner signed by Roosevelt “Velvet” Chapman — was a shrine to UD hoops.

But Parker didn’t just watch, he played the game well and was a member of the Salvation Army team in downtown Dayton when he died. He was just as gifted in the classroom, and yet when people remember him, the first thing they usually bring up is his impish charm and his admirable sense of right and wrong.

“After he died we got a letter from the parent of a young boy who was being bullied in school,” Sheila said. “He told us Parker stood up for his son, went to the principal to tell what was happening and then invited the child to sit with his group during lunch. The family wanted us to know how much that meant to them and to their son.”

Tears were rolling down Sheila’s cheeks as she recounted the message, then said softly: “He was an amazing child.”

Jim Froelich, who used to work with Scott in the ITS department of dining services at UD and whose daughter was Parker’s classmate and friend, agreed with Sheila: “He was the kind of boy you hope your daughter brings home one day.”

Parker’s life was shining on so many fronts last February when he was involved in a collision during an AAU game at Trent Arena and suffered a concussion. During a follow-up visit with doctors a few days later he was given a CT scan and a quarter-sized tumor was discovered just beneath his brain.

Doctors at Children’s Medical Center removed 95 percent of the tumor during an eight-hour surgery, but soon after Parker suffered a stroke and died.

“They asked us if we would be interested in talking to an organ donation representative,” Sheila said. “Scott and I had never talked about that because you just don’t plan on burying your child, but we just looked at each other and almost instantly said yes. Although we didn’t say it, we knew if somebody could have saved our boy with a donation we would have wanted it.

“And when you have such a massive sense of loss, you figure if this could help just one person, that would be the little glimmer, the one bright spot in all this hurt.”

Decision a blessing

The phone rang at the Vantilburg home at 4:30 a.m. on Feb. 12, less than 48 hours after Parker had died. Patty’s husband, Robert, went downstairs and became involved in a phone conversation.

“When he got back, he told me, ‘It’s the Cleveland Clinic and they have a liver for you,’ ” Patty said. “I said what are you talking about? I had just been on the transplant list 10 months and they had told me it might be two to three years.

“I called back and the coordinator told me about the liver – that it was a child’s and it had been split and doctors thought it was a good match – but I was unprepared and said, ‘How much time do I have to make a decision?’ She said, ‘You have 15 minutes, otherwise we have to move down the list.’ ”

Patty was born with PBC (primary biliary cirrhosis), an anti-immune disease that shows up later in life. She was in the early stages and though she tired easily, had swollen feet and was jaundiced, she said she didn’t feel that sick and was still working.

“You get the feeling, ‘I’m going to beat this on my own,’ but you’re not,” she said.

She woke her two children who were both home from college that weekend and though she was in tears and “kind of hysterical,” she said they talked sense into her quickly: “They said, ‘Mom, you have to do this. You might not get the chance again.’ ”

After a 10-hour surgery, she had Parker’s liver and since the transplant, she said: “I haven’t been sick a day. Not even a common cold.”

As Patty was going through her ordeal, Chester got a similar call from Miami Valley Hospital.

Diabetes had cost him his leg over a dozen years earlier and for the past year — a time when he was extremely tired and always cold — he had been on an exhausting dialysis routine at home.

He and his wife are raising their two grandsons – ages 14 and 12 – and they both are working. He’s in maintenance at Good Samaritan Hospital. He’s also deacon at St. Luke’s Baptist Church.

“He’s just a good, good man,” Sharri said. “He would do anything in the world for anybody. He’s always looking out for other people.”

That’s what made it so tough when he found out the kidney was coming from a child.

“When Chester found out it was a young person, he was really troubled by that,” Sharri said. “He said I’d rather not have a kidney if a child had to die for me to get it.”

Patty had similar thoughts: “Knowing it was a child made it very hard for me. Deep down you feel guilty about the whole situation.”

With Chester, Sharri tried to add perspective: “For the family to have the courage to make that decision at the time when they just lost their child … it’s a sacrifice you have to treat as a blessing.”

After the transplants, the recipients were told they could write anonymous letters to the donor family. If the messages were appropriate, Life Connection would forward them to Scott and Sheila and should they want to make contact back, they could. And only then could identities be revealed.

With Chester and Patty, that’s just how it happened.

“The loss, the grief, it never leaves,” Sheila said. “But now you can remember the happy moments, too. And seeing how Parker lives on in others now, that gives some kind of purpose to it, too.”

‘Dying as they wait’

The Bernard family has tried to do everything it can to create some positives from the overwhelming loss.

Five weeks after Parker died last year, they staged the first basketball tournament. It drew 24 teams and the proceeds went to the S. Parker Bernard Scholarship Fund, which benefits Bellbrook students who got good grades and participated in sports.

Last year scholarships went to three girls who now attend the University of Dayton, Ohio State and Capital University.

At this weekend’s tournament, people can watch games for a modest price, make donations to the scholarship fund, buy Parker’s Althetes-4-Angels bracelets, sign up to be organ donors and can volunteer to help put on the basketball competition, said Froelich, who helps run the tournament now.

Tournament information can be found at the website: www.athletes-4-angels.org. For organ donation info go to: lifeconnectionofohio.org.

Parker’s former Bellbrook teammates are now seventh-graders and their coach – Ron Keller – left an open spot on the bench and covered it with Parker’s No. 4 jersey as a way of remembrance at every game this season. Scott often attended the team’s practices after he finished work and he coached a third-grade team this year.

As for Peyton, who said she had no interest in going to UD a year ago (“It was like, ‘Oh great, I go to class and there’s my dad. I go out on Saturday night and there’s my dad”), she changed her mind after a campus visit. She fell in love with the place and has been accepted as a premed student next year. One day she wants to be involved in the organ donation process.

Last year she wrote a school report about how organ donation changes so many lives and Patty Vantilburg, for one, said she knows both sides of that story.

A few weeks ago at the Cleveland Clinic, she befriended Chelsea Lingenfelter, a 21-year-old girl from neighboring Wellsville, who had been diagnosed with adult liver cancer as a child. She had been waiting for another transplant for over a year and just a few days after Patty’s visit, Chelsea died during a transplant procedure.

“We need to get organ donation out there so everyone realizes what their gift can do,” she said. “Meantime so many people are dying as they wait. That’s why I am so thankful for Parker’s gift.”

Chester is, too: “I feel like I used to.”

Sharri said before her husband lost his leg, neighborhood kids used to come to the door of their Dayton home and ask: “Can Mr. Golson come out and play basketball with us?”

The thought made her laugh: “He always did. He loved to go out there with the kids.”

Tonight he’ll be able to do that again. Like he said: “It’s just like somebody turned the light on, man.”

And that’s just the glimmer Sheila, Scott and Peyton need to see.

About the Author