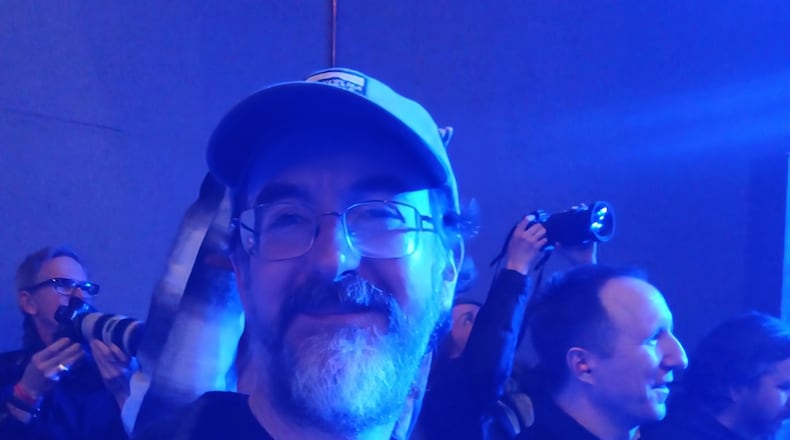

In 2014, a newly reformed Brainiac played a secret show at Blind Bob’s. Wettle was there. He looked around and thought to himself that the show should be documented.

He eventually clocked someone with a camera and said, Oh good, it’ll be available somewhere. Then he rewatched the concert on YouTube, with all of its whirling and twisting and nauseating movements.

“I was mad, kind of, which I realized is the wrong response,” Wettle said. “Why am I mad at somebody for not capturing it in the way I want it to be captured? I started thinking I should be the one that captures these moments.”

In 2018, Wettle met Jeff Jobson at a record store show in Louisville, Ky. Jobson has been capturing the sounds of the Louisville music scene since the late 1970s; he’s often at shows, hoisting a tripod and audio gear above the crowd, capturing the sounds of local music. Unlike the audio rigs of some lifer tapers — with dual boom poles, mixers — Jobson showed him you didn’t need to be official to chronicle something.

That’s when Wettle decided he could do an amateur version of what Jobson does. Wettle bought a slightly cheaper field recorder and took it to shows. He started with the entry-level TASCAM DR-05X, then eventually upgraded when he thought he lost the original. Wettle has recorded nearly 800 performances.

The 2019 documentary, “Brainiac: Transmissions After Zero,” solidified Wettle’s desire to record every show he attended.

“Who knows if this show, which seemingly is completely unimportant to everybody, will become important to somebody in 10 or 30 years,” Wettle said. “The band might become super famous, and somebody might want to do a documentary. Or there might be a mom that wants to have it. Even just that would be cool.”

Another part of his need to record is memory: he says he doesn’t have a good one. If someone posts about a show from 1994, he often wonders if he was there. He wishes he could sometimes go back in time.

“I’m jealous of the kids today. You can just take a picture of something at every show and have a memory of what they did forever,” Wettle said. “That’s what I’m trying to do. The core thing I get is some kind of memory.”

He often listens back to some artists, like Paige Beller (who Wettle calls a “once in a generational talent”), Nick Kizirnis and Cincinnati duo Lung. His bandwidth for music isn’t exclusive; he enjoys everything from hardcore to Americana. He can be found at record stores, venues and, sometimes, DIY basement house shows.

On top of the audio, he also grabs 30-second video clips from each performance and posts them to his Instagram account, @937stagefront. The tagline: “videos in front of mostly Dayton stages.”

At the recent show at Yellow Cab, as he recorded sets from Irby Ray, Empire Pool and Davin Tackett, Wettle showed me a Google Drive folder. The folder contained audio files from a Paint Splats show at South Park Tavern in 2021.

Though I no longer keep that band alive, and though that show was so far out of my memory, the folder made me think: who was I playing with? Was it a bad show? A terrible one? It reminded me of something that I didn’t think was important at the time, but was ostensibly important enough for Chris Wettle to record.

“Live music is an immersive experience that you’re in with a tribe of people, enjoying communally,” Wettle said. “And recording that changes it, but it captures the memory of being in a communal group of like-minded people. That memory is worth something if you were there, or even if you weren’t.”

He smuggles his low-profile rig into shows — maybe twice the bulk of a smartphone — and records bands from his hand, shirt pocket or on top of a bookshelf.

After shows, he cleans up the audio files in Audacity then sends the bands a message with a link to listen. He doesn’t post them, sell them, or upload them to Archive.org, as some tapers tend to do, but keeps them on a personal drive, because Wettle isn’t trying to preserve history. He’s just trying not to lose his own.

Brandon Berry covers the music and arts scene in Dayton and Southwest Ohio. Reach him at branberry100@gmail.com.

About the Author