“We value children most,” she said.

That’s the right goal, but she faces a lot of headwinds. Among them:

- The board rescinded its anti-racism resolution and replaced it with a confusing document that could be used to protest at the local school board level any teaching about race.

- Local school boards continue to be a target of small groups who believe it isn’t appropriate to teach about racism and how it continues to impact people of color today.

- The Ohio House has two pending bills, HB 322 and 327, that would prohibit the teaching of “divisive concepts,” another nebulous term opponents could use to protest just about anything. HB 327 would allow lawsuits against teachers and strip funds from school districts.

- Another House Bill, 298, would get rid of political appointees to the Ohio Board of Education. Right now, the board has 19 members, 11 of whom are elected and eight who are appointed by the governor.

The last point is an important one. Both McGuire and Laura Kohler, the former school board president, acknowledged politics have become a problem.

“I don’t ever recall politics being an issue during any discussion,” Kohler has said in interviews. “Members were focused on students, teachers and supporting school districts.”

But she said she saw a change “that intensified over 2021 as more conservative members were seated on the board. The rescission of the resolution to condemn racism and advance equity and opportunity for students who are Black, brown and indigenous people was a direct result of these board members responding to well-organized far-right constituents.” Kohler, a Republican, said she was forced to resign because she supported the anti-racism resolution.

McGuire voted against the resolution, which came on the heels of George Floyd’s murder, because she said she thought it was reactionary. She then voted for the repeal and believes the document that replaced it “gets back to the basic purpose of education, and that is academic excellence, academic achievement” that makes children successful in life.

But she did agree that politics have become a problem.

“Children care what you know when they know you care,” she said. “And so when we get so involved in politics that we forget about the students, I’m concerned about that.”

As she should be. There are polar opposites in this debate: people who want to talk race out of schools and others who don’t want us to hide from our past.

McGuire is hoping for reasoned, rational discussions — a hallmark of her long public service career — to help bridge that divide.

“If you come to the table with what I call ‘set in stone’ beliefs or values, which affects your behavior and the things you say, then there’s no opportunity to engage in respectful dialogue that brings dignity to all that are in the discussion, no matter which side you’re on,” she said.

Can she pull it off? Not many people have been able to bridge that divide.

Besides, McGuire argues that nothing in any of the pending House bills restricts educators from teaching about race.

“When I read that particular legislation (327), it’s about how the discussion (on race) is being facilitated, and what are the expected outcomes? And then even in developing your curriculum, you can do it in such a way that it meets the Ohio standards.”

That’s certainly one interpretation, but there are plenty of others that see these efforts as a way to stop discussing race in the classroom.

Education isn’t perfect; what is? But if there are concerns about what we’re teaching, and how, we need to get educators and a cross-section of parents (from all ideologies) to hash out what we should and shouldn’t do for the benefit of students.

That’s how you solve any issues. Leave politics out of it.

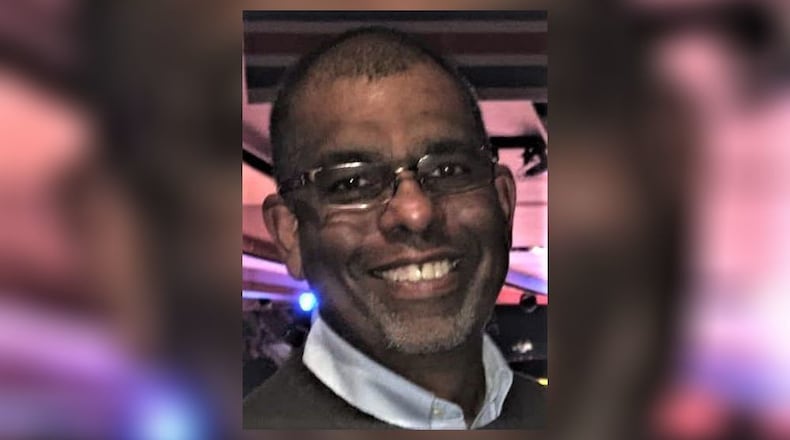

Ray Marcano is a long-time journalist whose column appears on these pages every Sunday. He can be reached at raymarcanoddn@gmail.com

About the Author