“It really helped us better understand the makeup of the worst of the worst — the most deadly tornadoes that affect us,” said Tom Johnstone, Meteorologist-In-Charge at the National Weather Service in Wilmington.

Japanese-American scientist Tatsuya “Ted” Fujita’s study of these tornadoes led to the development of the F-Scale (later refined to the EF-scale we use today), a system of classifying tornado intensity based on structural and vegetation damage.

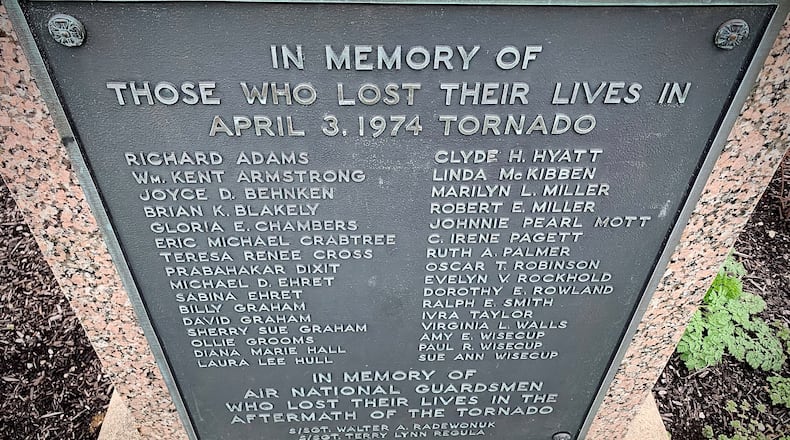

Fujita came to Xenia to study the damage after the tornado. The Xenia tornado was one of two that Fujita ever considered adding an F6 to his scale for.

“A lot of what we’ve learned about tornadoes in the last 50 years was really spearheaded by his work,” Johnstone said.

Tuesday’s weather in the Midwest illustrated the significant advances in storm forecasting, balanced with the fact that it is still not perfect. Meteorologists were able to determine well in advance that there was a higher-than-normal chance for tornadoes across a swath of multiple states, but not exactly where they would hit. Advance warning was given across the entire region, and tornadoes did cause significant damage in Indiana and Kentucky. No fatalities were reported.

Ohio valley as Tornado Alley?

While nationally, the number of tornadoes has remained relatively constant, Ohio has experienced an increase in tornadoes in recent years. Researchers at Ohio State University pointed out that in 2023, Ohio experienced more twisters than inches of snow in February.

“Tornado Alley” is often associated with states like Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska, but scientists have observed that it is shifting eastward to include Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee, per a 2018 study published in Nature Partner Journals.

Tornado activity has also become more concentrated in frequent outbreaks, or days with multiple tornadoes, according to Climate Central.

“When you go through the spring and summer months, you can say statistically, there may be two or three tornadoes every day through that season,” said Meteorologist McCall Vrydaghs. “But what we’re finding is that we’re having longer stretches without tornadoes, and then on a day when tornadoes occur, there tends to be more of them, they’re more intense, and they’re in areas that previously didn’t see that type of outbreak, including the Miami Valley and southwest Ohio.”

Why these weather patterns are changing is an ongoing area of study. Severe storms are complex, local, and short-lived events made difficult to study because of limited observational records or inconsistent reporting standards.

“I don’t think we have a convincing answer to why,” Johnstone said. “There’s some speculation that the changing climate is actually resulting in less wind shear … a key ingredient for tornadoes.”

Forecasting technology changes

Meteorologists do know more about how to detect tornadoes than ever before. In 1974, there was one radar site at the Cincinnati airport, which served all of Southwest Ohio, down to Lexington, Kentucky and southeast Indiana. Meteorologists then would only see the shape of the storm, and then use their training and expertise to understand whether it would develop into a traumatic storm.

Today, Doppler radar allows meteorologists to see the actual wind patterns, and see the ”descending rush of air that’s about to spin into a tornado before it even happens,” Johnstone said.

“Doppler radar has been a game changer,” he said. “We continue to increase the resolution on the radars, we can see better and better things. We continue to increase how quickly the radar scans are able to see updates more quickly.”

Additionally, dual polarization (or Dual-Pol) radar, transmits and receives both horizontal and vertical pulses, which supply forecasters with the horizontal and vertical dimensions of storms, allowing them to more accurately build a picture of what the storm looks like.

“With (Dual-Pol), we can see the difference between raindrops and ... trees being tossed into the air,” Vrydaghs said. “That can give us real-time clarification that tornadoes are on the ground, without having the visual of an actual tornado happening.”

Current doppler systems, however, are reaching the end of their lifespan, and the National Weather Service is in the process of considering the next generation of weather technology, Johnstone said. This could include several smaller radars to get more detailed pictures of a community, or a technology called a “phased array radar,” which is a collection of antennas that can more accurately scan for storms, and doesn’t have to mechanically rotate like a traditional radar dish.

The gold standard for determining if a tornado is on the ground is still a person’s eyeballs.

“Visual confirmation is number one, and number two is going to be radar,” Vrydaghs said.

Training, reaction for all of us

The National Weather Service offers free Skywarn Spotter Training to the public, both in-person and virtually, for people of all ages, and gives individuals the chance to learn more about weather and how to submit official storm reports.

“Tornadoes are a very rare occurrence,” Johnstone said. " We’ve come a long way but we’re still losing people with tornadoes, and we’ve got to continue to keep our focus on eliminating every death we can.”

The biggest thing a person can do is be aware of the weather, he said. People should have multiple ways to receive tornado warnings, including access to weather radio, sirens, or text alerts on their phones.

“One of the things that’s really advanced since 1974 is the ability to warn people. There was no weather radio in 1974,” Johnstone said. “Just paying attention and having multiple ways to get that warning, but then you have to act.”

Credit: Bill Lackey

Credit: Bill Lackey

Survivors of the 1974 tornado agree.

Jackie Brown, a 78-year-old Xenia resident, was working in Wilberforce University’s Carnegie Library in 1974 when a call came from a co-worker about the approaching tornado.

Brown said those in the library had no other warning and she credits Lynn Ayers’ call for helping save lives, as the tornado damaged the library.

“If you are told that you are in the path of a tornado and they tell you to take cover, I want (people) to understand they should follow instructions and do exactly what you’re told to do,” Brown said.

In particular, mobile home residents are at risk during a tornado. When a tornado watch is issued, that’s the time for people living in mobile homes or similar vulnerable structures to seek shelter.

Going underground during a tornado is the best option. If the house or business doesn’t have a basement, pick an interior room with no windows on the lowest level of the house.

“Even with 20 minutes of warning time … that’s not a lot of time to get yourself in someplace that is safer than your mobile home,” Johnstone said. “So those are the things people can really do: if you live in a vulnerable structure, or if you’re outside, you’ve got to have a plan to get somewhere safer during those tornado watch times.”

Credit: WALT KLEINE/JOURNAL HERALD

Credit: WALT KLEINE/JOURNAL HERALD