Don Hayashi thought of his wife’s cousin, now 85, who returned to her home in Hiroshima that morning to retrieve a forgotten handkerchief, fearful that she would get in trouble with her teachers. Most of her classmates died that day.

Five miles away, a key artifact from this historic event has stood sentinel at the United States National Air Force Museum since 1961: Bockscar, the specially-modified B-29 Superfortress that dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki 80 years ago, on Aug. 9, 1945, three days after the first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

“In terms of world history, Bockscar is probably the most important artifact in our collection,” said Doug Lantry, curator and historian for the museum’s research division. “Helping preserve and interpret Bockscar is a great responsibility and privilege. The artifact signifies the end of the world’s most destructive war and the beginning of the atomic age. For us it is also a landmark in the development of American air power and the creation of the United States Air Force.”

The Peace Museum and the Air Force Museum may seem a few miles and a world apart, but in many ways they share a common mission: learning from the past.

“Most of what survives from the past that’s meaningful are things that embody an experience; they serve as landmarks for reflection and learning and thought,” Lantry said. “We can think more clearly about the present and the future when we know where we come from, and objects like Bockscar tend to root us to what happened and why, and how we got the way we are now.”

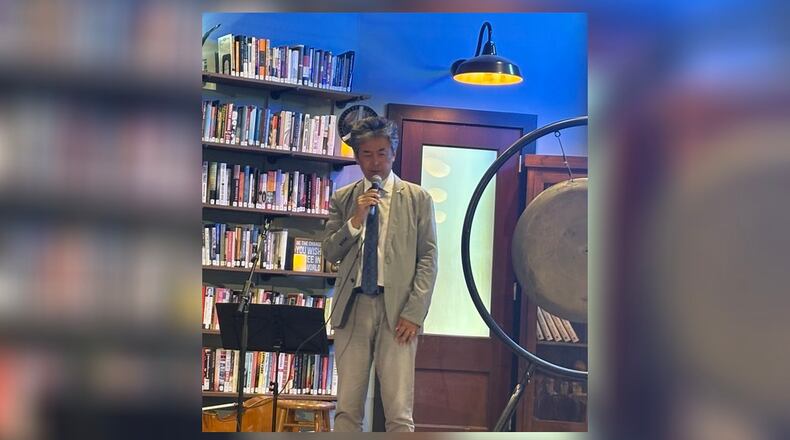

The Peace Museum’s executive director, Alice Young-Basora, struck a similar note in her opening remarks Tuesday night. “Tonight we honor the past, not to dwell on sorrow, but to learn from it,” she said.

Instead of bitterness or even sorrow, the prevailing spirit for the “80 Years of Peace Commemorative Evening” was one of reconciliation and hopefulness. Prior to the ceremony, children and volunteers engaged in the Japanese tradition of folding origami paper cranes – “a sign historically of hope for a better future,” explained Hayashi, a third-generation American whose grandparents emigrated to the United States in the early 1900s.

Eva Weber, the mayor of Augsburg, Germany, attended the ceremony with a contingent from the Dayton Sister City.

“This bell ringing is not only a moment of remembrance, but a symbol of hope,” Weber said. “It shows how the relationship between former enemies has grown into friendship, and it shows that hope can emerge from pain.”

The gong-ringing ceremony was live-streamed in communion with a similar event in the Dayton Sister City of Oiso, Japan, timed to coincide with the dropping of the first atomic bomb at 8:15 a.m. Aug. 6, 1945. “We ring the bells to remember those who perished, and those who suffered, but also to promote peace and stability in the world,” said Hayashi, president of the Dayton chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). “It is important for Japan and the United States to show solidarity and support for each other.”

Kishimori, who is Consul General for Japan for the Dayton region, made the trip from regional headquarters in Detroit in part because of his mother’s history as a survivor. Growing up in Hiroshima, he initially held mixed feelings toward the United States. After a 45-day, cross-country bus trip during his youth, his feelings became more positive, eventually leading him to choose the U.S. for his 40-year diplomatic service.

“The more I saw of America, the more I liked it,” he recalled. So the spirit of reconciliation at the Peace Museum event struck home with Kishimori; he particularly loved the participatory nature of the gong-ringing ceremony and the sing-along to “Let There Be Peace on Earth,” accompanied by retired Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra cellist Jane Katsuyama.

No commemorations were planned at the Air Force Museum, where Bockscar is introduced simply as “The Aircraft that Ended WWII.” Japan surrendered unconditionally Aug. 14, 1945, five days after the bombing of Nagasaki. The exhibition text panels make virtually no mention of the human toll of the bombings, other than from a strategic standpoint: “The devastation caused by (the first) atomic bomb brought no response to the call for unconditional surrender.”

The Bockscar exhibit has largely avoided the controversy that has at times engulfed the Enola Gay exhibit about the plane that dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The originally planned exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum faced fierce blowback from some critics who believed that the text minimized Japanese aggression while maintaining too intense a focus on the victims’ suffering.

During his 25 years at the Air Force Museum, in contrast, Lantry has never encountered any controversy surrounding Bockscar. In part that is due to its mission, he said: “One of the things we exist for is to be a memorial or a touchstone for our Air Force and our veterans, so they can come in with their children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren.”

Even 80 years later, that history is very much front and center for the general public as well. The interest in seeing Bockscar, Lantry said, remains as keen as for other highly significant artifacts, such as the Memphis Belle B-17 Flying Fortress aircraft and John F. Kennedy’s Air Force One aircraft.

“People walk through the door and say, ‘I want to see the airplane that dropped the atomic bomb,’” Lantry said. “And people share family stories about where they were at the end of the war and where they were at the beginning of the nuclear age, and what was their family history at the time. And everybody has their own story or their parents’ or grandparents’ story that circles back to the airplane.”

Lantry’s job, as he sees it, is to bring artifacts into historical perspective: “We need to ask what the thing itself is trying to tell us. They can’t speak for themselves, but if you ask the right questions, and you are a good observer, you can find things from the artifacts that you can’t get in any other way. And that’s why we preserve things like Bockscar in the first place. Why do we need the thing, when we have the story already? We need the thing because the thing is the best and most real and most tangible link to the past that we have. It is the survivor of the past.”

Over the years the Air Force Museum has hosted several guest speakers associated with the atomic bombings, including Enola Gay navigator Theodore Von Kirk and Enola Gay pilot Paul Tibbets, a longtime Columbus resident until his death in 2007. In 2014, retired Col. Joseph Sweeney – son of Bockscar pilot Maj. Gen. Charles Sweeney – delivered a lecture at the museum.

The Bockscar exhibit script was curated strictly from the point of view of the Air Force, Lantry explained: “Our interpretation of Nagasaki focuses on the mission and the airmen, what happened and why and who did it, and how they did it. There are many, many places where you can find all sort of arguments and opposing points of view. There’s a whole a whole wide world of interpretation about the events of 1945.”

One of the most important voices that has emerged for atomic bomb survivors is author Susan Southard, whose book “Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War,” won the Dayton Literary Peace Prize for Nonfiction in 2016. The narrative follows the lives of five survivors of the atomic blast that killed an estimated 74,000 people and wounded another 75,000. At the age of 30, she was moved to tears by a speech from a survivor. But it wasn’t until years later, in 2003, that as a first-time author she embarked on what turned into a 12-year journey to tell the stories of Nagasaki survivors.

“What happened beneath the mushroom cloud remains relatively unknown in our country; it’s not looked at very much,” Southard reflected. “I wanted readers to know these survivors as stories and as people, not just photos on a bulletin board.”

It wasn’t until Southard came to Dayton for the first time, to accept the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, that she encountered Bockscar in person. “I had written about the mission, but to see the plane in person was astounding,” she recalled. “It brought tears to my eyes.”

Nagasaki survivor Kiyomi Joyce, for her part, didn’t feel the need to visit the Bockscar exhibit after moving to Dayton in 1997. “It’s just another plane; it’s a museum piece,” she told the Dayton Daily News in 1998. She had married an American soldier, Paul Joyce, in 1952, when he was stationed in Japan during the post-war occupation. She raised her two daughters in the United States, becoming an American citizen at the age of 80.

An air raid convinced Joyce, then 14, to stay home from school on the day that Nagasaki, in her words, became “ash city” – a decision that may have saved her life. She was cutting pockets for a blouse for her home economics class when she heard the plane overhead. She waited for the familiar sound of bombs dropping, but heard nothing. Instead she witnessed an eerie orange glow in the sky and an unexpected warmth against her skin.

“I was scared and ran into a closet,” Joyce recalled. “There was a sound like an earthquake and the house started shaking.”

Later, when she walked down the street, she witnessed passersby screaming and crying for help. Joyce walked that night with her aunt and four cousins to a friend’s house in the country.

Joyce lived in the Dayton area until her death in 2022, serving as an active member of the JACL and frequently sharing her story with the community. She didn’t do so with any sense of anger or vengeance, but out of concern for the future. “The earth has to be worried,” she said.

Southard said she encountered the same stoicism, courage and commitment to peace in countless of the hibakusha – as survivors are known – she interviewed during the course of her research.

“It was a great privilege to know them and to experience the grace of their humanity,” Southard said. “They used their stories to speak out about peace, a peace without nuclear weapons.”

Only the hibakusha can truly comprehend what happened underneath the mushroom cloud, she added: “The survivors have opened a discussion we should be having about nuclear weapons, not just then, but now. There are 12,400 nuclear weapons that could actively deployed for use on command, or that could be deployed by nuclear error or error by nuclear terrorism. The survivors’ stories matter because we want to make sure that the people of Nagasaki are the last atomic bomb victims.”

As Nagasaki survivor Yoshida Katsuyi once told her, “The basis of peace is understanding the pain of others.”

About the Author