Medicaid pays for half of all medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid addictions in Ohio — more than $52.6 million in the first half of 2018 for just the treatment drugs.

But the current patchwork system of oversight puts public dollars at risk of going to programs that aren’t following the practices shown to be the most effective, or worse, treatment drugs like Suboxone are being sold illegally on local streets and in jails.

RELATED: Addiction doctor: Drug dealers are profiting off Medicaid

“The fly-by-night, Medicaid-funded MAT treatment programs that have popped up have terrible track records. They are milking the system and not improving the lives of half the people who need their help because the state isn’t tracking their efficacy,” said Jan Lepore-Jentleson, executive director of East End Community Services. “Treatment programs need to be monitored for effectiveness.”

Dayton Daily News Investigates followed the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on opioid addiction treatment in Ohio to determine if that money is going to solutions shown to lead to long-term recovery more often. We did this investigation to serve as watchdogs over your tax dollars and help our readers navigate the complex system of treatment providers.

This story is part of our Path Forward initiative in which we dig into our community's most pressing issues.

Our investigation shows:

- Medication-assisted treatment using FDA-approved drugs to wean patients off opioids is administered by a wide range of doctors and facilities that fall under various agencies' oversight and licensing or certification requirements.

- Clinics or doctors who see fewer than 30 patients at a time don't have to be state-certified and comply with the stringent standards of those who treat more people and are certified. That also means they aren't being inspected regularly like the larger providers and the state relies on complaints to police them.

- Cash or self-pay clinics have opened as demand for addiction treatment has increased. They often charge as much as $250 out-of-pocket for an initial visit, services that would be free to the patient if they qualify for Medicaid, and often don't provide much counseling or other supportive therapies shown to reduce relapse rates.

- Several major medical organizations say medication treatment should be done with other methods like counseling, cognitive behavioral therapy and/or peer supports. But there is no requirement that a MAT-licensed doctor do that themselves. They are supposed to refer patients to other providers or support groups and document whether the patient attends. No one routinely checks if doctors are complying with those requirements.

- The Ohio Department of Medicaid couldn't provide data on how much it spends on treatment or MAT drugs at certified versus non-certified providers.

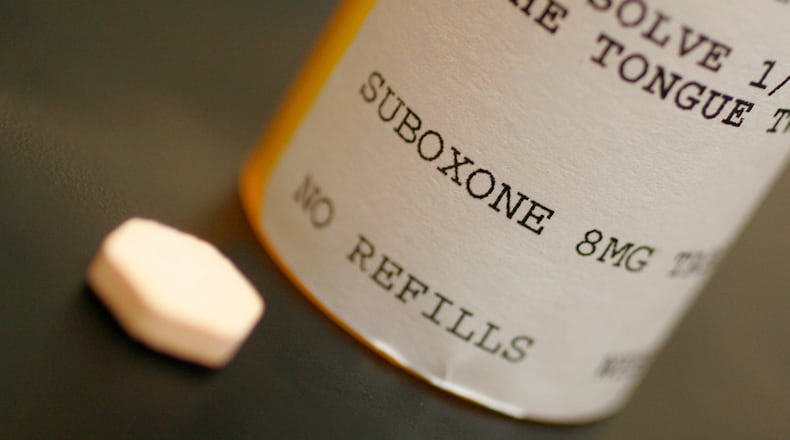

- Suboxone, the brand name for one of the treatment drugs, is being sold or traded for other drugs on the streets and in jails at Medicaid's expense. Suboxone is highly available on Dayton streets and it's been increasing, according to the most recent Ohio Substance Abuse Monitoring Network report. The drug is coming from legal prescriptions sold illegally on streets.

- Information about how to find quality care and who is certified for various services can be difficult to find, especially on publicly accessible websites. For example, the only publicly available list of doctors who can prescribe Suboxone is outdated and includes a half dozen physicians who have lost their medical licenses and at least two who are dead.

Under direction from the state legislature, the State Medical Board of Ohio is working to update its rules for all MAT providers.

The new rules will tighten limits on how much Suboxone can be prescribed in the first 90 days, specify the types of counseling services a patient should get, and require patients to get more frequent urine tests to prove that they’re using the drug and not selling it. Those not meeting the standards would be subject to action against their license.

The board continues to review the proposed rules but they’re expected to be adopted in some form in early 2019.

“We want patients across the state to be able to be in quality environments where they can experience successful recovery,” said Dr. Rick Massatti, Ohio’s designated opioid treatment authority at the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services.

RELATED: Montgomery County Coroner says local overdose deaths are climbing again

The updated rules will better define best practices, he said, recognizing that illegal diversion of MAT drugs happens.

“We’ve got to be careful it’s not just throwing money at the thing and not providing the kind of, I’d call it, almost wrap-around services that you see in successful programs,” said U.S. Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio.

Massatti and others said they are in favor of expanding options beyond the large certified treatment centers because not every patient needs or wants the “Cadillac” treatment.

"We are trying to find a point of equilibrium," said Dr. Stuart Leeds, an assistant professor of family medicine at the Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine and a practicing physician. If regulations are too strict, he said, "access would suffer badly, and people would just not get treatment at all."

Federal money expanded access

In 2016, as opioid-related deaths began to soar to record levels in Ohio, the state’s treatment capacity lagged. The Health Policy Institute of Ohio ranked the state’s ratio of medication-assisted treatment providers to overdose deaths as the third lowest in the nation that year.

So Ohio used some of the $26 million it received from the federal Cures Act in fiscal year 2017 to train more doctors in addiction treatment.

RELATED: Local providers to be trained to treat opioid addiction

Suboxone is the most common of several brand names for tablets or films that combine buprenorphine with naloxone. It blocks withdrawal symptoms. It can cause a high but is weaker than heroin or methadone and has a ceiling where taking more won’t have any effect.

Suboxone has become the most popular MAT drug among doctors because it doesn’t have the abuse potential of methadone, which can only be administered at federally regulated facilities.

Federal waivers for doctors to prescribe buprenorphine products were authorized under the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 and are referred to as DATA 2000 waivers. The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act expanded buprenorphine prescribing privileges to nurse practitioners and physicians assistants in 2016.

Ohio had only about 250 doctors who’d gone through the training to get the waivers as of 2015.

“We really had limited access to MAT,” Massatti said.

Now Ohio has more than 1,050 physicians who have received waivers.

General practitioners with waivers to prescribe buprenorphine are a critical part of ensuring access to treatment for all who need it, experts said, because nine Ohio counties don’t have any facilities dedicated to substance abuse treatment, and others have one or two.

Caseload data shows the majority of doctors use the waivers to treat existing patients in their own practices, Massatti said, rather than opening up specialized Suboxone clinics.

A challenge for general practitioners could be connecting their patients to required counseling services, Leeds said, because it’s a lot of work to communicate with outside services and keep tabs on whether the patient attends.

“You have to know what’s in your community that’s available and you have to make a road for a patient to get there,” he said. “Any of these medications should be used in that context of a treatment plan. If it’s not, almost all of it’s going to fail.”

But there are doctors who aren’t being vigilant about this requirement, Leeds said, and that could hurt their patients’ chances of recovery.

“What does worry me somewhat is people cutting corners, people acting in good faith, wanting to provide these services but not dotting their I’s and crossing their T’s about all the protocols they should be following and the resources they should be making available to the patients,” he said. “Substandard care is going to lead to treatment failures and those are going to lead to Suboxone diversion. Suboxone is going to end up in the general population. It’s already there.”

Montgomery County’s Alcohol Drug Addiction and Mental Health Board recommends that people seeking treatment go to state-certified facilities that offer cognitive behavioral therapy in addition to medication and the board only contracts with those facilities.

“Access to medication will relieve the person of the physical and some of the psychological stress of addiction, but it doesn’t change the person’s long-term thinking and feelings that drive their behaviors,” said Jodi Long, director of treatment and supportive services for the Montgomery County board. “You always want a combination.”

The proposed rule changes for MAT doctors include definitions of what constitutes appropriate behavioral therapy, but some comments submitted to the state board noted that too strict of a definition could mean some patients are left without services.

“The proposed rule inhibits physicians from becoming buprenorphine prescribers, and decreases access for patients who may be unable to commit the time and/or money required for counseling,” said Gregory Boehm, president of the Ohio Society of Addiction Medicine.

He and others argue some trials show no improved outcomes from adding counseling to medication for addiction treatment. However the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have all issued numerous reports stating that behavioral therapy combined with medication significantly increases long-term recovery rates.

Not all clinics take insurance

A quick web search for “Dayton Suboxone clinic” will net thousands of results for doctors who have opened their own shops to address the opioid epidemic. These clinics must have DATA 2000 waivers and staff with active medical licenses, but no other certification as long as each prescriber treats no more than 30 patients.

If a prescriber treats more than 30 patients, they must get an additional license from the Ohio Board of Pharmacy. That license comes with much more scrutiny, including mandatory background checks for employees and regular inspections.

About a dozen clinics are operating in the Dayton area without such a license by staying under the patient limit. The Board of Pharmacy is responsible for investigating complaints of someone going over this limit.

The state mental health board has an additional certification for centers that offer services such as counseling and in-patient treatment, which has similar levels of scrutiny to the pharmacy board license. The smaller clinics aren’t required to get that certification either.

RELATED: What Ohio did with the feds’ $26M for addiction treatment

Some of these non-licensed, non-certified clinics accept Medicaid and private insurance and some don’t.

“There are Suboxone providers that are kind of going outside of Medicaid all together,” Leeds said.

These clinics — which charge patients hundreds of dollars out-of-pocket — are under even less scrutiny because the department of Medicaid isn’t looking at what services are being billed to catch any abnormalities.

The Path Forward: Addiction in Dayton

- » Vets twice as likely to fatally OD -- what the Dayton VA is doing about it

- » ‘Life Changing Food’: This eatery hires only people recovering from addiction

- » Local chef in recovery serves up message of hope

- » New challenge for recovering addicts: Finding a job

- » Can Dayton go from 'overdose capital' to a model for recovery?

- » 'A whole new life:’ Local people share their path out of the depths of addiction, and into long-term recovery

- » Mother of 7 rebuilding family after addiction

- » A day with Dayton's overdose response team

In some cases clinics are charging cash for a visit to get a Suboxone prescription, but then the patient fills the prescription using Medicaid.

“I know for a fact that’s happening because my patients have reported it to me more than once,” Leeds said. “To me that strikes me as sort of failing in our primary mission here, which is to take care of people.”

Other doctors and treatment providers in the area have reported the same story from patients and said they are concerned about the quality of care people are getting when they simply Google Suboxone clinics and find one with walk-in appointments and cash payments.

“It’s often medication without the treatment,” said Wendy Doolittle, CEO of McKinley Hall, a state-certified treatment center in Springfield.

“The prescribing of medication is what got us into this mess,” said Jade Chandler, president of Woodhaven Residential Recovery Center in Dayton, a state-certified facility that uses some MAT for withdrawal management but focuses much more on behavioral therapy.

READ MORE: Experts say cash clinics divert treatment drugs to Springfield streets

A 2017 study of opioid treatment providers in Ohio by Dr. Ted Parran of St. Vincent Charity Medical Center in Cleveland found that cash clinics may be prescribing more than 16 mg of Suboxone per day, which is the typical dose prescribed by clinics that take insurance.

“That then really becomes a moral and ethical issue for prescribers if requiring large amounts of cash for visits is associated with prescribing higher doses of an opiate that has a street value and can be diverted in order to generate money perhaps for office visits,” Parran said earlier this year.

Patients need to be better educated that they don’t have to go that route and that they can get help signing up for Medicaid or other health insurance to cover the cost of treatment, Leeds said.

“That’s kind of a scam operation and they need to do a little shopping to find out that this care is available and that it’s affordable,” he said.

The Dayton Daily News attempted to contact cash clinics in Montgomery County, including going to the listed addresses, but they didn’t return multiple calls for comment or were no longer operating at those locations. Many others listed online had disconnected phone numbers.

Some patients might prefer a self-pay option, Massatti said, because they don’t want to comply with the stricter counseling requirements that might accompany insurance coverage.

RELATED: County’s opioid prevention efforts get $1.5M to combat overdoses

It’s unclear how much diversion of Suboxone is happening from those paying cash and those using Medicaid or other insurance providers.

Treatment providers and users surveyed for the most recent Ohio Substance Abuse Monitoring report on drug abuse trends in Dayton said Suboxone is being sold in the parking lot of many clinics in the area for about $20 per 8 mg strip. One treatment provider stated in the report, “There are a lot of shady clinics, and people know where they are, and they know how to get it.”

Investigations and lost licenses

Suboxone clinics have been investigated, along with doctors being suspended or losing their licenses for not following MAT rules.

In July of 2016, the Ohio Attorney General’s Office and the Drug Enforcement Agency raided the Springfield office of Reasonable Choices Inc., which was a state-certified MAT clinic at the time.

Dr. Richard Potts permanently surrendered his medical license in April 2017 in lieu of further investigation into allegations of failing to maintain minimal standards of care.

Attorney General Mike DeWine’s office said the case is still open, but the clinic’s director Brenda Griffith said the business has since gained an international accreditation, state certification and approval to bill Medicaid. They now operate at a different location in Clark County and have three doctors and a physician assistant who each have waivers to do MAT.

RELATED: Recovering addicts take their fight to the boxing ring

She defended clinics that accept cash payments, which Reasonable Choices does while also accepting Medicaid and other insurance, as offering an option for clients who are working and can’t make multiple visits per week for counseling.

“We don’t want to overdo it,” she said. “We find the best fit for the patient.”

The Dayton Daily News investigation also found more than a dozen doctors statewide who are listed as having active buprenorphine prescribing waivers, but have either lost their medical license or been disciplined for violations related to prescribing practices.

Neither state nor federal authorities were able to provide information on when doctors were granted their waivers so it’s unclear if they were issued before or after the disciplinary action.

RELATED: $8M grant to connect employers with workers in recovery

Responsible clinics should be checking regularly and randomly whether their clients are actually taking the Suboxone prescribed to them, experts said, whether they are self-pay or accept insurance.

Reasonable Choices in Clark County maintains a relationship with the Moorefield Twp. police so that they are alerted if a client gets in trouble for selling Suboxone, Griffith said. They do mouth swabs, urine and blood tests and random pill counts to prevent misuse of the MAT drugs they prescribe.

“We do take a lot of precautionary measures,” Griffith said.

Complaint-driven system

If the updated state MAT guidelines are approved and go into effect early next year, there still won’t be any routine monitoring in place to make sure non-licensed and non-certified clinics are operating up to those new standards.

The Ohio Board of Pharmacy inspects only the larger facilities it licenses and conducts checks of the state’s prescribing database to see if anyone is going over their patient limit — 30, 100 or 275 depending on their level of waiver.

Any other investigations into substandard care at the smaller, unlicensed clinics would need to be initiated by a complaint from another prescriber, a patient or a family member, according to Ali Simon, public and policy affairs liaison for the pharmacy board.

RELATED: Ohio gets more firepower in fentanyl fight

Ohio has taken steps to promote greater access to MAT and put into place strong safety measures to ensure responsible treatment, the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services said in a statement.

That includes strengthening the Ohio Automated Rx Reporting System (OARRS) that tracks prescriptions, including buprenorphine.

“Any abnormal prescribing patterns are discernible through OARRS,” the statement says. “The Ohio State Board of Pharmacy investigates suspicious activity and refers cases to the State Medical Board for disciplinary action.”

To ensure that Medicaid spending on medication assisted treatment is appropriate, Ohio Medicaid has a robust program integrity unit, the statement also says, which works closely with the Ohio Attorney General’s Office’s, Ohio Auditor of State, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and managed care plans.

“This coordinated approach has been nationally recognized as a best program integrity practice,” the statement says.

The state mental health agency also is using a portion of its federal grant funding to provide one additional investigator to the State Board of Pharmacy.

RELATED: County awarded $670K in federal funds for opioid treatment

Montgomery County’s Alcohol Drug Addiction and Mental Health Board recommends that people seeking treatment go to state-certified facilities that offer cognitive behavioral therapy in addition to medication and the board only contracts with those facilities.

“Access to medication will relieve the person of the physical and some of the psychological stress of addiction, but it doesn’t change the person’s long-term thinking and feelings that drive their behaviors,” said Jodi Long, director of treatment and supportive services for the Montgomery County board. “You always want a combination.”

MORE COVERAGE OF OPIOID CRISIS:

Ohio Lt. Gov. Mary Taylor opens up about her sons’ opioid addictions

How Mexican drug cartels move heroin to Ohio streets

Local people share their recovery stories

HOW TO GET HELP: An opioid addiction resource guide

Levels of certification for medically-assisted treatment

Individual prescribers:

Doctors, physician assistants and nurse practitioners can attend an eight-hour training to get a DATA 2000 waiver to prescribe buprenorphine from the DEA. They must follow Ohio Medical Board rules for MAT but can treat up to 30 patients at a time without any further certification.

OBOT clinics:

An Office-based opioid treatment license is required for anyone wishing to treat more than 30 MAT patients at a time. The Ohio Board of Pharmacy regulates these licenses which come with increased standards for inspections and reporting.

OMHAS certification:

The Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services certifies facilities that want to offer other addiction treatment services in addition to MAT. This includes counseling and residential treatment.

Other accrediting agencies:

Several agencies offer accreditation in the addiction treatment field that facilities can choose to apply for including the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF), Council on Accreditation for Children and Family Services (COA), The Joint Commission

Doctors disciplined

More than a dozen Ohio prescribers who have current buprenorphine waivers have either lost their medical license or been disciplined for violations related to prescribing practices. Here are some examples.

•Dr. Franklin Demint is on probation with the Ohio Medical Board, but working at a Middletown Suboxone clinic. Due to marijuana dependency, he entered into a consent agreement that permanently bans him from prescribing narcotics but makes an exception for buprenorphine, according to a consent agreement. The state makes exceptions for doctors who have themselves struggled with substance abuse as long as they comply with their probation and can demonstrate a pattern of sustained recovery. Demint couldn’t be reached for comment.

•Dr. Rose O. Uradu, who operates treatment clinics in Kentucky and Ohio, finished serving an Ohio license probation earlier this year after the medical board found she issued buprenorphine prescriptions to twice as many patients as her waiver allowed. She was flooded with patients when another clinic closed down, her attorney Fox Demoisey said. Uradu has also been sued by the Justice Department for billing Medicaid and Medicare for patient evaluations and urine tests that allegedly were never performed at her Kentucky clinic. “It’s about correct compensation,” Demoisey said. “It’s not about competency.”

• Dr. Nilesh Jobalia of Hamilton will go on trial in 2019 for allegedly prescribing both opioid pain killers and methadone without actually seeing patients, and in unlawful combinations, according to court and medical license records. “Because the matter is before the court, it would be inappropriate for me to comment on the precise clinical reasons for the combinations of drugs charged in the indictment,” his attorney David Axelrod said. “We do, however, intend to prove that Dr. Jobalia was an extremely careful physician who always acted in the best interests of his patients, and is not guilty of the offenses charged in the indictment.”

ABOUT THE PATH FORWARD

Like all of you, we care deeply about our community, and want it to be the best it can be. There is much to celebrate in the Dayton region, but we also face serious challenges. If we don’t find solutions to them, our community will never be its best.

We have formed a team to dig into the most pressing issues facing the Miami Valley. The Path Forward project, with your help and that of a 16-member community advisory board, seeks solutions to issues readers told us they were most concerned about.

Follow the project on our Facebook pages and at DaytonDailyNews/PathForward, and share your ideas.

By the numbers

$52.6 million: Medicaid spending on medication-assisted treatment drugs in first half of 2018.

1,050: Ohio medical professionals with waivers to prescribe buprenorphine.

30: patient limit per prescriber before a state license is required.

$20: street value of an 8 mg Suboxone strip.

About the Author