Gilliland will join three other inductees into the 2017 National Aviation Hall of Fame, including Mercury 7 astronaut Scott Carpenter, turbojet engine inventor Frank Whittle, and four-time space explorer and NASA administrator Charles Bolden.

Dayton could lose Aviation Hall of Fame ceremony

They will join more than 230 others named over more than half a century to the Hall of Fame inside the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

“In the broad sense, what we’ve got is a group of individuals that represent the dawn of the jet age all the way through deep space exploration,” said Ron Kaplan, National Aviation Hall of Fame enshrinement director.

More than 140 aviation-related voters on a NAHF Board of Nominations choose inductees.

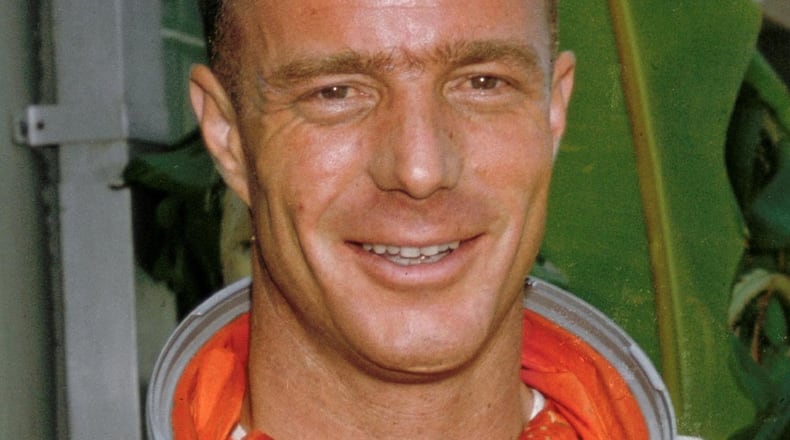

Gilliland was recruited by Lockheed “Skunk Works” aircraft designer Clarence “Kelly” Johnson to fly pioneering test flights of the record-breaking SR-71 Blackbird, a needle-nosed shaped supersonic fighter that could fly higher than 80,000 feet at speeds above three times the speed of sound.

Gilliland, 90, of Palm Desert, Calif., was the first to fly in the twin-seat jet, staying in the secretive flight program 12 years. The Memphis, Tenn., native, logged more test flight hours above Mach 3 than any test pilot.

The spy jet carried a pilot and a reconnaissance systems operator “but for the first flight Kelly Johnson thought, and I agreed, it was too dangerous to have anybody else back there,” he said. In December 1964, the SR-71 first took flight, with Gilliland at the controls alone.

On one flight, instruments showed the aircraft nearly broke out of his control near Mach 3, he said. On another, a red light warned of a canopy malfunction.

“It was dangerous,” the Korean War veteran said. “I was so lucky to be alive now and then, too.”

He witnessed the curvature of the Earth and the blackness of high altitude, but on some flights he was too busy looking at gauges inside the cockpit to notice. “Sure enough,” he once told someone who asked, “the higher it goes, the darker it gets.”

Pilots were told not to fly over Canada or Mexico in case they had to bail out, he said. “When you’re doing something like this you do have a lot of emergencies,” he said.

The spy plane had a legendary reputation flying over hostile territory to gain intelligence data on adversaries.

“They never shot down any SR-71s and they served six presidents,” he said.

A retired Marine Corps two-star general, Bolden spent 34 years in the military and aerospace world, including 14 years in the NASA astronaut corps. Bolden flew four times on the space shuttle and was a fighter pilot in the Vietnam War. The Columbia, S.C., native was a shuttle pilot and commander. He was part of crews that deployed the deep-space peering Hubble Space Telescope, and the first joint U.S.-Russian shuttle mission, according to NASA. He was inducted into the NASA Astronaut Hall of Fame a decade ago.

Carpenter, a Boulder, Colo., native who died at age 88 in 2013, was the second American to orbit Earth. His space capsule, Aurora 7, circled the globe three times May 24, 1962, on a nearly five-hour pioneering space flight. The former naval aviator and Korean War veteran later became an “aquanaut.” He spent a month underwater off the shore of LaJolla, Calif., in a Navy experiment in the Pacific Ocean and later trained astronauts in the weightless-like environment of water to prepare for space.

Whittle, an aviation pioneer born in England, built the first turbojet engine in 1937. His work led to the development of the jet aircraft industry in the United States. “(It’s) amazing how many Americans do not realize that our current jet aircraft industry is largely due to development of engines by Frank Whittle back in England in the 1930s,” Kaplan said.

A Royal Air Force test pilot who initially received skepticism and doubt about his findings, Whittle would patent the turbojet engine he said was needed to propel planes to heights and speed needed to achieve longer distances than propeller-powered planes could reach. He moved to the United States and became a research professor at the U.S. Naval Academy. In 1996, he died at age 89 in Maryland.

About the Author