“If even one active-duty service member or gov’t employee deployed overseas is forced to spend $1,170 to "prove" their child is worthy of citizenship, that is one too many,” tweeted Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-IL).

The changes seemed destined to cause the most red tape and heartburn for members of the military who wanted to adopt a child while serving overseas, members of the military who have a child overseas, members of the military who are married to non-US citizens, or service members who recently became U.S. citizens - as their kids born on overseas duty would not automatically be treated as U.S. citizens.

“That is an abominable and anti-patriotic position for the Trump Administration to take,” said the group Vote Vets, a veterans group which has been a critic of President Trump.

On call with reporters, @uscis says their analysis on the new policy would have affected 20 to 25 people a year over the past five years...

— Patricia Kime (@patriciakime) August 29, 2019

On a Thursday conference call with reporters, senior immigration officials struggled at times to describe exactly how the changes would impact the kids of U.S. government workers - whether born or adopted overseas - as officials shied away from some concrete examples offered by reporters about American families overseas.

The officials said the changes made were only technical in nature, and were pursued because the State Department at times was refusing to give passports to some children born to U.S. citizen families working for the government overseas.

In other words, the Pentagon thought these children were U.S. citizens - but the State Department did not.

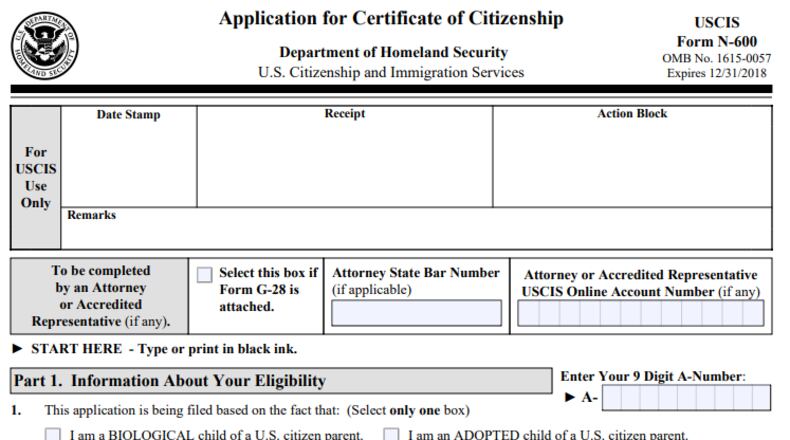

"The hurdle that exists now is that State (Department) is not issuing passports for this population," one official said. "And we're issuing certificates of citizenship."

Those cases mainly seem to center on children adopted by U.S. citizens when serving overseas, and on immigrants serving in the military who are legal permanent residents, and not yet a full U.S. citizen.

"We've tried to emphasize that this really is a very small population," one official told reporters, saying a review for the past five years showed an average of 20 to 25 cases.

"We are not changing anything about birthright citizenship," one official said.

But the confusion about what was changing or not changing was being felt on Capitol Hill.

Encouraged to see @USCIS clarify that the revised policy for children of military and government personnel abroad only applies in select and unique circumstances. I will continue to follow developments to ensure service members’ families are treated with the respect they deserve.

— Rep. Pete Olson (@RepPeteOlson) August 29, 2019

President Trump’s anti-immigrant policies are appalling; denying citizenship to children of service members born abroad is cruel. If America closes her doors to a service member’s child, who exactly is welcome in America?https://t.co/nyIU75mprR

— Jim Cooper (@repjimcooper) August 29, 2019

I wrote to @DHSgov and @USCIS demanding they rescind this offensive policy update. If even one active-duty servicemember or gov’t employee deployed overseas is forced to spend $1,170 to "prove" their child is worthy of citizenship, that is one too many.

— Tammy Duckworth (@SenDuckworth) August 29, 2019

Read my letter below ⬇️ pic.twitter.com/Yyd2hPvG7h

"Children born while their parents serve overseas, often risking their lives for this country, deserve better," said Rep. Pete Olson (R-TX).

Immigration advocates and lawyers were also still trying to figure out what was happening, as the bottom line seems to be some U.S. citizens working for the U.S. government overseas will encounter more red tape to make their kids - born or adopted overseas - American citizens.

"This memo really caught us by surprise and immigration lawyers I know were scrambling to figure this out," said Scott Hicks, an immigration attorney from Ohio.

"Unfortunately this is a really complex area of law with many related subsections that control depending on the facts," Hicks said, reflecting the confusion about how the policy was updated.

About the Author