In addition to failing to provide adequate charity care for those in need, many nonprofit hospitals are leaving patients in the dark as to the real cost of their care. Yes, federal rules require all hospitals to post their prices online in a searchable and accessible format. But in Ohio, hospitals often flout these rules. A recent survey of 2,000 American hospitals revealed that only 57 of 223 Ohio hospitals reviewed – or merely 26 percent – complied with federal price transparency rules. This leaves patients without the information they need to make informed health care decisions, and it gives hospital opportunities to overcharge unwitting patients.

Which is exactly what they are doing. According to a report published by RAND Corporation, Ohio hospitals are charging patients with private insurance 268% more on average than they charge Medicare patients for the same services. Recent reporting by Axios was equally troubling. They found that that The Cleveland Clinic and Summa Health System (Akron Campus), both nonprofits, charge patients on average 4.2 times and 7.6 times as much as what it cost to provide them care.

Together, these unscrupulous hospital practices are contributing to a growing medical debt crisis. According to KFF Health, nearly 100 million Americans are carrying medical debt, many of them hailing from Ohio. Unfortunately, in Ohio, there are few consumer protections for patients carrying medical debt. The law favors health care providers, like big hospitals, over working-class patients struggling with medical bills that they can’t afford to pay.

Under Ohio law, medical providers can sell off a patient’s medical debts. They can seize a patient’s bank account to collect a medical debt. They can even send a patient’s debt to a collection agency without first offering a reasonable payment plan. So, consumers should be aware that without more robust protections in state law, getting sick could eventually cause them to lose their savings.

Many hospitals in Ohio are not above using every using every available point of leverage to squeeze their patients for unpaid medical bills. Recently, Kaiser Health News teamed up with NPR to examine the billing practices of a “diverse sample of 528 hospitals across the country.” Of the 28 hospitals that KHN reviewed in Ohio, sixteen allow patients’ medical debt to be reported to credit agencies, a practice that can have long-lasting damaging effects on their credit and on their financial well-being overall. Beyond that, 20 hospitals will even sue their patients – or take other legal actions – to collect a medical debt. And yes, nonprofit hospitals are among those who use these coercive debt collection tactics.

Nonprofit hospitals should act as genuine nonprofits and fulfill their charitable missions. When they don’t, policymakers in Ohio should these hospitals accountable. No hospital should get a free ride on the taxpayer while simultaneously exploiting the patients who rely on them for care.

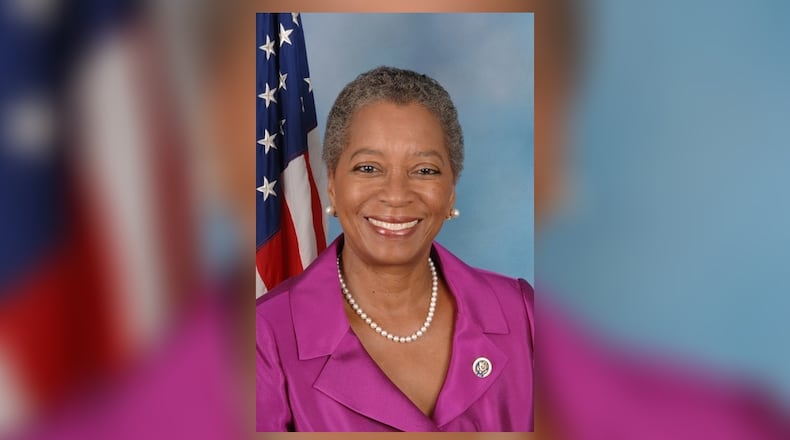

Former Del. Donna M. Christensen, D-V.I., is a member of the Consumers for Quality Care board.

About the Author