It seems as if Dayton’s being engulfed by violence. Maybe it’s not really that bad. But it sure feels that way. Look at the data.

Just last week, the Dayton Daily News reported that two people were killed and seven injured in a series of apparently unrelated shootings and stabbings. Police say one man, angered customers called him out for cutting the line at a food truck, shot a patron in the leg. Through January 17, police reported three homicides, 36 aggravated assaults, and 13 cases of shooting into habitations, according to WRGT-TV.

The statistics, sadly, show these acts aren’t outliers.

Of the country’s 19,495 cities, towns, and villages, Dayton ranks comfortably in the top 20 as one of the most dangerous cities in America. One list has Dayton in the top 15. The CBS News Murder Map had Dayton at No. 5.

Granted, these subjective lists use different criteria to determine rankings. But whether Dayton sits at 5, 15, or 75, it still means it ranks in the top 1% of America’s nearly 20,000 cities.

Sadly, there don’t seem to be any long-term solutions to a problem that has perplexed American cities, including Dayton, throughout its history.

In 1970, the New York Times noted the “frightening” increase in Dayton’s crime rate. Dayton earned the moniker of America’s most violent city in 1973 and 1974, according to the Dayton Police History Foundation. In 1974, the New York Times wrote, “Dayton shaken by 5 killings in 5 days.” W.S. McIntosh, the revered civil rights leader at the time, died after being shot while trying to prevent a robbery at a downtown jewelry store.

Name the decade, and you’ll stories of violence, along with very well-meaning groups devising plans to reduce it (Let’s not say “stop it” because that’s not going to happen).

And in each decade, nothing works to great significance.

I know local groups make a difference in individual lives. They work with youth on after-school efforts, so they have a safe place to study or get a meal away from neighborhood distractions and bad influences. They help them chart a career path and with basic life skills.

But if we take a step back and look at the causes of violence, the occasional success might be the best we can do. Why? Because violence tends to be based on power, respect, and control.

Research shows that anti-social young men from dysfunctional families who have low self-control fit the personality traits of violent criminals. Chances are they don’t have a decent job or live in a stable environment since they associate with people like them.

They’re adrift and believe guns and violence give them power and control in a way they don’t have in their lives. They don’t have the power to change their economic status, so they don’t feel they can control their fate. So how do they gain respect?

At the tip of a smoking gun. You will respect me, or I’ll put a cap in you.

Will any of the current community efforts make a real dent in crime and violence? They haven’t to date. Maybe programs like the $28.8 million “Hope Zone” anti-poverty effort in northwest Dayton or the “Gun Violence Reduction 2023 and Beyond” make a sustained difference.

History shows they have a tough road ahead. Maybe they can change the narrative.

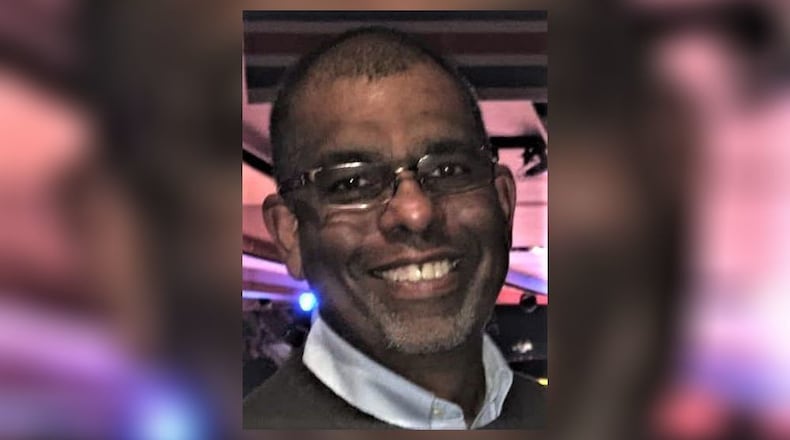

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday. He can be reached at raymarcanoddn@gmail.com.

About the Author