The Raise the Wage Ohio Coalition needs to collect 413,446 signatures to get its constitutional amendment before voters. If it passes, the current $10.10 minimum wage for non-tipped workers would gradually rise to $15 an hour by 2026.

Workers’ groups support wage increases, while businesses would rather the market dictate what they pay. We also know that voters favor a higher minimum on the state and federal levels, with various polls tracking at about 60% approval.

People look at issues as black-white. It’s good, or it’s bad. But the nuances often help determine whether a policy is worth implementing.

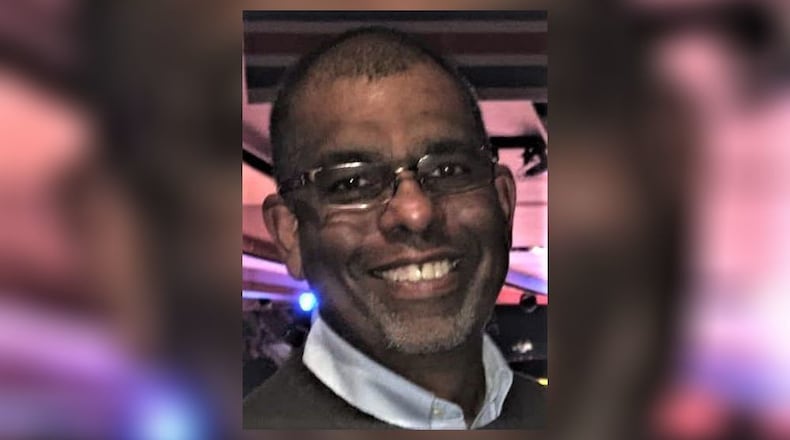

Kevin Willardsen, an associate professor of economics at Wright State University, helped me understand that this isn’t a good vs. bad argument.

“There are no solutions, only tradeoffs,” Willardsen said. “Some people are going to benefit from this policy, and some people won’t.”

Labor is like any commodity. If the price increases, businesses buy less, Willardsen said.

Research supports that conclusion. The Congressional Budget Office wrote that when wages increase, some businesses will employ fewer workers. The Harvard Review said that workers with a higher minimum salary could make less money because businesses cut hours to make up for the increased costs.

Still, the overall impact of increasing the minimum could benefit the majority of workers. If a business has 100 workers but can’t operate with less than 99, it could let one person go while everyone else makes more money.

“The benefit to those 99 more than offsets the loss to the one,” Willardsen said.

There’s one of your tradeoffs.

Willardsen also asked a simple yet overlooked question — what are we trying to accomplish?

Proponents say a higher hourly rate will help lift people out of poverty and provide a living wage. Those are noble outcomes hard to argue with — until you look at the nuances.

When wages rise, inexperienced and low-skilled workers are the first ones that get let go. “If you really want to help poor people, the best thing you can do is give them lots of options, because wage isn’t the only reason people choose a job,” Willardsen said.

Some workers, for example, might prefer a lower-paying job that provides more flexibility regarding time off and setting the days they work. Others prefer one environment over another. A bartender who had been in the industry for more than 30 years once told me wouldn’t take any other job because he liked talking with and meeting lots of different people.

Willardsen and I spoke about economic theories, whether $15 an hour really is a living wage (I don’t think so), and the debate among economists about the employment effect when the minimum wage rises.

Raise the Wage Ohio should get the signatures it needs and many thousands more. It’s hard to say “no” to the base argument that more money helps improve the economic quality of life.

But the nuances add a complication, especially when faced with an either/or proposition Ohio voters will likely face, and I would wager, pass. Some 37% of Ohio workers make less than $15 an hour, higher than the national average.

Three states have enacted a minimum $15 wage, with 11 more to follow suit through 2026. My only question: In 2026, the buying power of $15 will be about $13.31.

Then what do we do?

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday. He can be reached at raymarcanoddn@gmail.com.

About the Author