That’s a part of it, but it’s not the most crucial part.

It’s a law issue. Not law enforcement, but existing laws that handcuff authorities from being able to take guns away from those with mental health problems.

The Maine gunman, a U.S. Army reservist, (his name doesn’t deserve acknowledgment), had a troubled past.

Police sent out a statewide alert after the gunman threatened his base and fellow soldiers, the Associated Press reported. Before that, family members contacted authorities because the gunman said he was hearing voices that were saying terrible things about him, NBC News reported. In July, his unit’s commander sent him for psychiatric treatment, and he spent two weeks at an inpatient facility.

Still, he purchased firearms legally just two weeks before a shooting rampage that left 18 innocent people dead.

There are so many unanswered questions — why was he allowed to buy a weapon; how could he have slipped through the cracks — but a closer look at Maine’s “Yellow Flag” law shows the problem.

From the time his family called authorities five months ago, and from the time he underwent evaluation, authorities should have been able to take any guns he had and prevent him from buying others until a doctor said he had improved.

That’s not radical. Nine states have red flag laws that allow the temporary removal of firearms if a suspect is a danger to himself or others. Ohio is not one of them and should be.

But in Maine, it’s difficult to remove a firearm from a dangerous person. The state’s cumbersome process requires a suspect to go into protective custody. Then a medical practitioner must determine that the person poses a threat, and that determination needs to be endorsed by a judge or justice.

How about this? Someone has an apparent mental health issue. Authorities go to court and get an order allowing for the temporary removal of all firearms. Then if an assessment comes back OK, give the guns back. If not, hold them.

We have to remove as many steps in the process as possible. If someone’s hearing voices, or making violent threats, then there’s no need for a court to wait for an evaluation.

There is no constitutional guarantee that the mentally ill have a right to a firearm. None. These sorts of prohibitions have withstood court challenges and enjoy strong bipartisan support. Nearly 9 out of 10 Republicans and Democrats believe the mentally ill should not be able to buy guns.

I already hear the objections. Well, if you start with this, it’ll give the government a reason to take all of our guns.

No. Only if you have a mental illness.

The issue isn’t law enforcement. It’s the laws they’re meant to enforce.

Ohio Senate Bill 357 would have allowed police officers to seize a firearm from a person with a severe mental illness — which would have been an enormous step in the right direction — but that provision has been removed.

That’s too bad. It’s a step in the wrong direction. Just ask Maine.

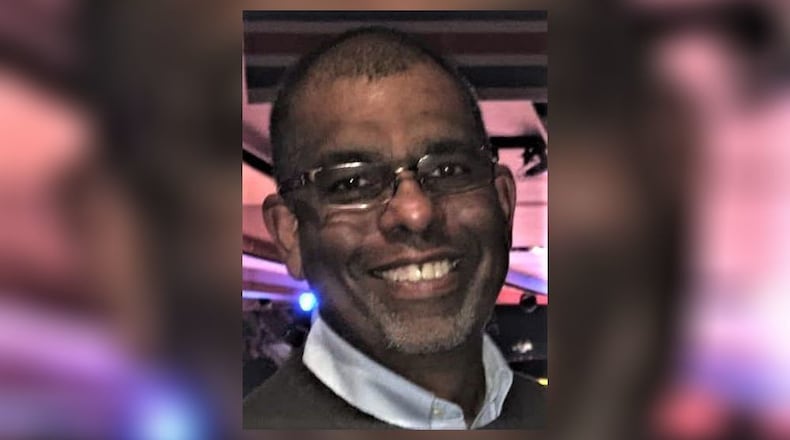

Ray Marcano’s column appears each Sunday on these pages. He can be reached at raymarcanoddn@gmail.com.

About the Author