Over half of Earth’s land suitable for growing crops is agricultural, including about half of all land in the US. Food systems, from growing crops to retail and food service, inherently require resources and modern food production represents an exacerbated use of environmental, social, and economic inputs which are largely externalized through petroleum and agricultural subsidies.

A 2021 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations determined that nearly 90% of the global $540 billion agricultural subsidies cause harm to human health, fuel climate change, negatively impact ecosystems, and drive inequality, as most of these subsidies exclude small scale production. These damages have been estimated at greater than $12 trillion per year, far surpassing the value of the food produced.

Large-scale food production is almost entirely reliant on petroleum use and disruption of carbon sinks including forest, prairie, and wetland. Carbon sinks are ecosystems where plants capture carbon through photosynthesis and store it in soil and vegetation. These altered lands, instead, drive further emissions, as nearly all modern agriculture uses petroleum-based fertilization and routinely tilled soils no longer regenerate or store nutrients. Cropland is more susceptible to invasive vegetation, diseases, and pests, which means they are more dependent upon chemical controls, an additional carbon cost.

Mechanical harvesting, processing, hauling, refrigeration and retailing all demand more energy and produce carbon emissions. When unwanted food is sent to the landfill, it breaks down slowly in a low-oxygen environment, producing methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. This means that food waste creates enormous carbon and economic costs that are often obscured.

It seems illogical to continue producing, consuming, and disposing of food in this way, but globally petroleum and monoculture cropping are heavily subsidized, which keeps this practice inexpensive. The International Energy Agency reports global subsidies at an all-time high of over $1 trillion for 2022. US annual agricultural subsidies range from approximately $20-$50 billion, the majority of which are provided to the top 10% earning businesses. Global meat and dairy subsidies are estimated at over $200 billion annually. This is important because meat and dairy have a vastly higher carbon footprint than plant-based diets, accounting for over 75% of all agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and over 80% of agricultural land use worldwide.

These figures are astounding, yet they illustrate a problem with achievable solutions to be hopeful about. As individuals, we can contribute to change and make consumer decisions that are beneficial to our health, support local economies, and help slow the driving forces of climate change.

Smart shopping to minimize perishable food waste is an important first step. Purchase produce, meat, dairy and other short shelf-life foods that will be consumed. This also helps to ensure food is fresh and safe for the consumer. Dry and canned foods last much longer and are best for “stocking up.”

Sourcing local is fun and rewarding. It can reduce carbon emissions associated with transportation and help prevent spoilage. Growing produce at home or in a communal space is empowering, and farm markets are a great way to connect with local producers directly.

When food must be disposed of, composting is a solution for keeping it out of the landfill and recycling nutrients to build better soil. Approximately one third of waste in landfills could have been composted.

Dietary choices are perhaps the most challenging part of this conversation because this topic is so personal. It isn’t fair to ask everyone to be a vegetarian, but plant-rich diets have a much lower carbon footprint due to the high resources associated with producing meat and dairy. Simply adopting a higher variety of foods and focusing on whole ingredient foods instead of processed products generally results in a healthier, more climate-friendly way of eating.

Finally, we can advocate for policy change to make food access more equitable and redirect profit and subsidies to support local, regenerative food supplies. Food is life and community, and it should be enjoyed as such. We have the power to make it equitable and environmentally sound as well.

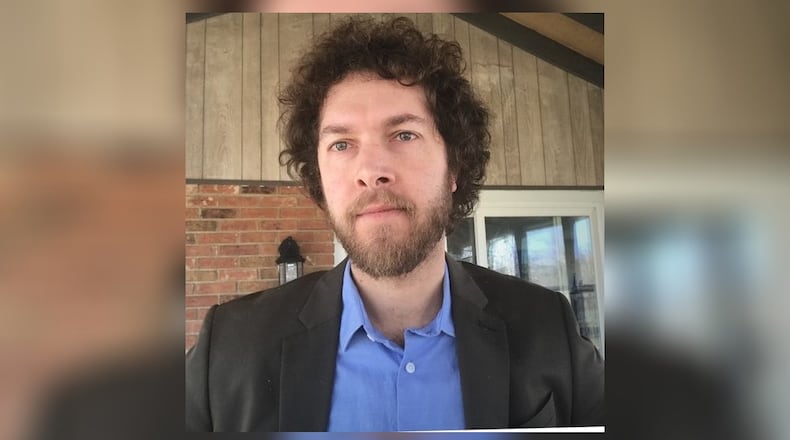

Tim Pritchard is the Sustainability Manager for Five Rivers MetroParks, an avid gardener, outdoor enthusiast, and ecological restoration advocate.

About the Author