Early life

Stepp grew up near the farm village of Peebles. His father, Elias Stepp Sr., was a self-styled lay preacher who was frequently quoting scripture.

He had several siblings, including younger brother Ernest Stepp, who was also a member of his alleged gang.

“As a very young boy, his father used to take Bill down to the Cincinnati riverfront docks and bet on him in fights against older adults,” Dayton Daily News staff writer Wes Hills said in 2008. “Bill was a very, very physically strong man ... He was an outstanding street fighter.”

A non-drinker, Stepp was said to be “affable and gracious at times” but was also known for his vicious temper. He was expelled from high school at age 16 for assaulting a gym teacher.

Highlights of Stepp’s early police record

On his way to wealth, Stepp accumulated an amazing record of getting off lightly. Here are a few highlights from dozens of his arrests in the early years:

• Jan. 6, 1958: Charged with involvement in burglary, Columbus. Reduced to receiving stolen property. $25 fine and one year probation.

• Oct. 2, 1959: Charged with assault-to-to against Columbus police officer. Entered plea to aggravated assault. Three days in jail, $100 fine.

• Aug. 9, 1960: Charged with assault with intent to rape, Cincinnati. Six months in county jail, $200 fine on charge of assault and battery. Jail sentence set aside; given five years probation instead. Probation was later reduced to two years.

• Sept. 28, 1962: Charged with aggravated assault, Dayton. Six-month jail term and $200 fine suspended on condition that he pay victim’s hospital costs.

Critically wounded

In 1963, Stepp was shot three times and critically wounded by farmer James Branham Sr., who accused him of pistol-whipping his adult son, James Jr.

The elder Branham was charged with shooting to kill after he wounded Stepp. Local law officials showed no eagerness to push the case however, and a county grand jury did not vote for an indictment.

Stepp spent 24 days in the hospital, eventually recovering, but the injuries caused health issues for him for the rest of his life.

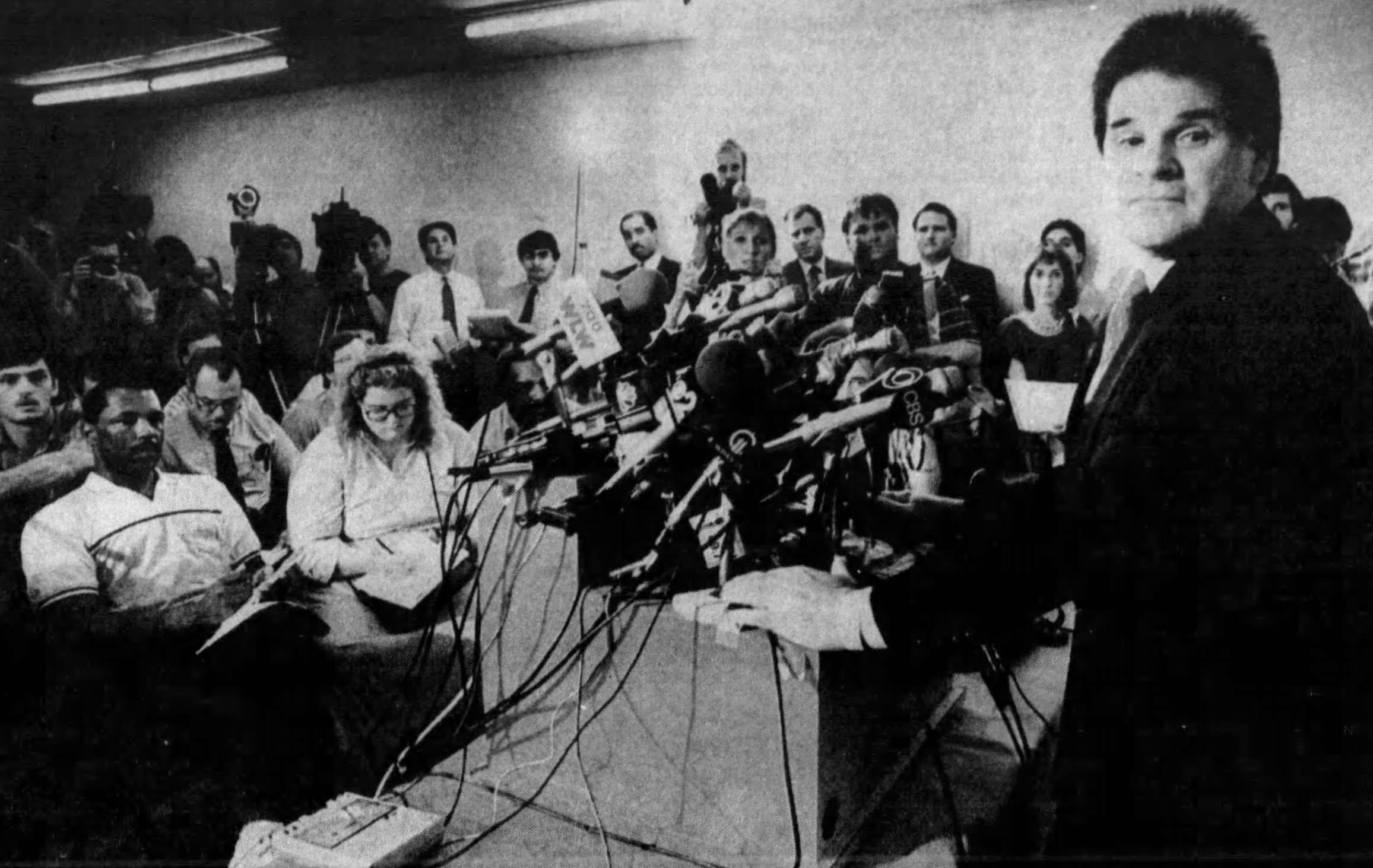

Credit: File photo

Credit: File photo

Notorious gang

The Stepps and their associates were tabbed “the notorious Stepp gang” in 1966 by then Ohio Attorney General (later U.S. Senator) William B. Saxbe.

The attorney general said the gang had been responsible for a series of crimes, including extortion, burglary and larceny by trick.

Several of Stepp associates had been convicted and sentenced to long prison terms. But not Bill or his brother, Ernie.

In 1969, 33-year-old Bill had been arrested more than 30 times since 1955. Assault-and-battery charges in which victims were brutally beaten were the most common charges.

However, convictions were very few against Stepp.

In a 1973 interview, Steep said talked about his rough past.

“About 10 years ago, I had a lot of problems. I liked to fight. I didn’t start fights, but I never backed away from one. When you get involved in violence, you eventually end up stepping on the wrong toes...But there is absolutely no such thing as a Bill Stepp gang,” he said. “It just doesn’t exist.

Dayton Daily News editorial

By the end of 1966, the record got so absurd that a Dayton Daily News editorial summarized the situation this way:

“However appalling the arrest record run up by Dayton thug Bill Stepp, the record run up by area law enforcement agencies and courts is just as appalling.

“Stepp has been charged with rape, larceny by trick and with repeated incidents of assault and battery and aggravated assault.

Credit: File photo

Credit: File photo

“In many beating cases, witnesses have withdrawn their complaints, some saying they were afraid to testify. In other cases, charges have been dropped by law agencies or reduced to misdemeanor class. Though placed on probations, Stepp never has been charged with a probation violation.

“A couple of cases simply have been lost in the maze of the legal process.

“And that, police officials say, is only the tip of the iceberg. Police officials all say they want Stepp, and maybe they do. Those who have had him, however, have seen him slip away, and the courts often seem to have looked the other way.

“There is no evidence that Stepp has felt more heat than a sunbather.”

Wanted dead

The Stepp brothers frequented Newport and Covington for several months as it was the gambling hotbed of the time.

On Dec. 9, 1969, the Dayton Daily News printed a headline that read: ‘Kill” Contract Out for Stepp

Sources had told the DDN that “a ‘contract’ was out calling for he execution of Dayton underworld figure William E. (Bill) Stepp.”

Also named in the contract was Bill’s younger brother, Ernie.

The two were being blamed by the victims of a $100,000 holdup of a big-time card game in Covington, KY.

Credit: File photo

Credit: File photo

During the holdup four masked men carrying shotguns made off with an estimated $80,000 in cash and $40,000 in jewelry. The gamblers, eight men and one woman, surrendered the money and jewels after being forced to strip off their clothes to hinder pursuit.

Bill and his brother had not been publicly seen for a while, but Bill’s wife, Lucy, said her husband and his brother were still in town. Other reports said the two were in Florida.

Drag racing

After gaining notoriety in the 1950s and ’60s with a long series of arrests, Stepp seemed to stay mostly out of trouble during the 1970s. He spent a lot of time at his Billy the Kid Auto and Van Conversion shop and at racetracks across the country.

He had been involved with racing cars for much of his life, but starting in 1968, he went legitimate. Before long, he was the owner of two of the hottest pro stock cars in the National Hot Rod Association.

“There’s a lot of hard work and sweat,” Stepp said, “There’s a lot of traveling in this sport too ... a lot of sleepless nights to and from the track. A guy has to be pretty dedicated.

“I just found that it’s impossible to function as an owner, driver, mechanic and PR man all in one. My best talents were in owning and PR, so I took that direction.

His distinctive red, white and purple cars, most with his “Billy the Kid” logo, won the modified elimination title in the prestigious Gatornationals in 1969. His car was runner-up in the Indianapolis nationals in 1972 and a winner at the National Dragster Open in Columbus in 1973.

Ed Crowder, general manager of Kil-Kare dragway in Xenia, said Stepp was always friendly around the track.

“I don’t know anything about his personal business, but at the track he has always been a gentleman to everyone,” he said.

In 1982, Stepp was inducted into the National Hot Rod Association’s Division III Hall of Fame.

Home raided

Stepp’s house on Winterhaven Avenue in Harrison Twp. was raided in March 1984. However, the FBI lost 78 of the 129 items taken in the raid.

More that a dozen federal agents using dogs from Wright-Patterson Air Force Base trained to sniff out drugs were at the scene.

Seized items included $508,000 in a grey suitcase in the attic, $50,020 in a Gucci designer bag and $2,650 in a woman’s boot.

Items lost included “four wax paper envelopes containing white powdery substance,” brass knuckles, three handguns, assorted papers concerning dealings with a munitions plant in Dominican Republic and telephone bugging alert devices.

Credit: File photo

Credit: File photo

Agents also found that Stepp was in possession of confidential police files about himself from the Dayton Police Department.

Former Dayton Police Lt. Daniel Baker told the DDN that an FBI agent had been using a prostitute-informant who had worked for Stepp for years. Stepp had used her to get information on the police, secret service, ATF (Federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms), FBI intelligence and the police organized crime unit.

In 1985, a U.S. District Judge ruled that Stepp would not get back $558,110 of the amount seized, ordering it be forfeited to the federal government. Prosecutors claimed the money was related to drug sales.

Once again Stepp avoided any serious jail time.

He died of natural causes at the age 73 in 2008.

GEM CITY GAMBLE

A project from the Dayton Daily News

Former Dayton police Detective Dennis Haller’s career spanned a dark time for the Dayton Police Department. Haller was a source for Dayton Daily News reporter Wes Hills, who retired in 2004 after 30 years at the paper, and agreed to share information with Hills on the condition it stay confidential until Haller’s death, which happened in 2023.

Now, we bring you Gem City Gamble, a series that uses Hills’ interviews and notes to shed new light on the largest police corruption scandal in city history and how police wiretapping and a spurned bookie may have contributed to the downfall of baseball legend Pete Rose.

About the Author