Legislators have until Feb. 13 to approve a new map, he said. They would do so with a clause declaring an emergency – meaning the bill would go into effect immediately upon becoming law – due to the impending primary deadline, Huffman said.

But the delay in establishing new congressional districts has already derailed at least one campaign.

Franklin Mayor Brent Centers, who announced in August he would run in the Republican primary for the District 1 seat now held by U.S. Rep Steve Chabot, has suspended his campaign.

Centers puts the blame squarely on uncertainty about which new district his home county of Warren will be in.

“We have a filing deadline to run for Congress, and the congressional maps aren’t out,” he said. Centers said he could still legally run, but wants to represent his home community. The uncertainty on district lines not only inhibits campaigning, but makes it practically impossible to fundraise, he said.

Centers said he had endorsements from law enforcement, every mayor in the county and more than 50 other public officials.

“Everyone was wanting this change, and then the system got in the way,” he said. “This system is designed to support itself. This whole process has just validated why I was running.”

The Ohio General Assembly moved the filing deadline for U.S. House seats to March 4. The partisan primaries for those seats will still be May 3.

“Even with that, we’re losing all of this campaign time where the incumbent can still campaign no matter where the district lines are” Centers said. “This is just designed, whether intentional or unintentional, to help the incumbents keep their seats.”

How we got here

Under a 2018 constitutional amendment the General Assembly is charged with creating a new congressional map. Due to 2020 census results, Ohio has to lose one of its 16 current U.S. House seats.

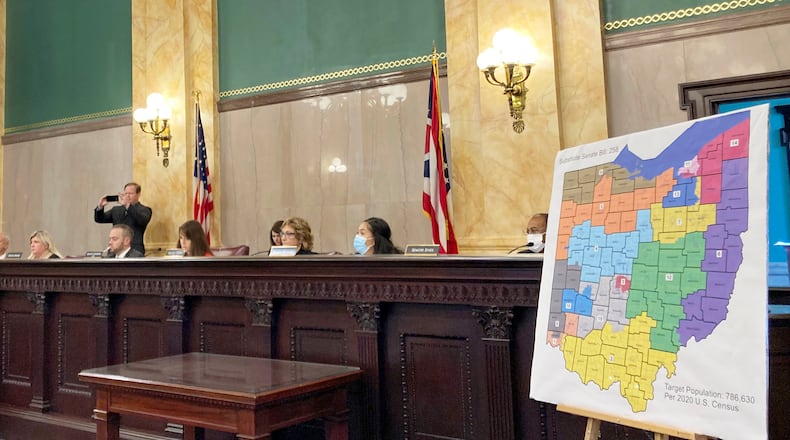

Legislators passed a map in mid-November without any Democratic support, meaning at best it would be in effect for four years. Opponents – progressive and voting-rights groups – immediately sued, and on Jan. 14 the Ohio Supreme Court agreed that, like the state House and Senate maps it had overturned only days earlier, the congressional map was gerrymandered to favor Republicans out of proportion to their actual electoral strength. The court threw out the congressional map and gave legislators 30 days to draw a new one.

Huffman said for a new congressional map, backers would try to get a two-thirds vote in both houses. That’s 66 votes in the House and 22 in the Senate; currently Republicans hold 64 House and 25 Senate seats.

If legislators cannot agree on a map, the task will revert to the Ohio Redistricting Commission on Feb. 14, Huffman said.

Centers said that considering state officials used all 10 days they were allotted to approve new state House and Senate maps, he doesn’t expect any swifter movement from legislators on the congressional map.

The Ohio House Majority Caucus also expects hearings on congressional maps “as early as next week,” said Aaron Mulvey, majority press secretary.

Ohio Senate Democrats have not heard directly about Republicans’ plans, said Giulia Cambieri, communications director for the Democratic Caucus.

“We haven’t seen their new map proposal and haven’t received a notice for the next meeting of the General Government Budget committee,” she said. That’s the committee to which a Republican placeholder bill has been referred.

State Sen. Rob McColley, R-Napoleon, filed the bill Jan. 26 in anticipation of a new map proposal. Senate Bill 286 declares the General Assembly’s “intent to enact legislation establishing revised congressional district boundaries.”

McColley was the official sponsor of the now-overturned map as well.

How it’s going

Since this is the first time redistricting has been done under the system created by constitutional amendment, “everyone is feeling their way through,” said Mark Caleb Smith, chair of the Department of History & Government and director of the Center for Political Studies at Cedarville University.

“I am not sure what incentive Democrats will have to support any map that has a Republican slant that outweighs typical, statewide voting patterns,” he said. “The Ohio Supreme Court’s willingness to strike down a map that favors Republicans suggests Democrats are in a slightly better position than in the past. Voting on a strict party line may be the best way to get the best map for the Democrats. Add to that the generally difficult partisan environment, this is not a good recipe for working together.”

That divide is reflected in the results of a Gongwer/Werth poll of state legislators from the last week of January. About one-quarter of General Assembly members answered questions about redistricting. Roughly half of respondents from both parties agreed that the district-drawing process should be revised further. But there the similarities ended.

More than two-thirds of Democratic respondents said elected officials should be removed from the redistricting process, while three-quarters of Republicans said they shouldn’t.

Similarly, nearly half of Democrats said it’s possible to take politics out of redistricting, while almost nine out of 10 Republican respondents said that can’t happen.

Those attitudes may be linked to each party’s perception of public interest: all Democratic respondents said their constituents were “very” or “somewhat” interested in redistricting, while more than a third of Republicans said their constituents were only “somewhat” interested – and more than half said constituents weren’t interested at all.

Compare and contrast

Groups like Fair Districts Ohio, which lobbied legislators for months to pass a map that matched the statewide partisan breakdown and held a public competition to create examples, remain interested and involved.

On Feb. 3, Fair Districts Ohio held a virtual news conference to detail one of its contest-winning maps. The intention was to show that it’s possible to draw truly representative mas that meet constitutional requirements, and tp provide a template for the official map-drawers’ discussions, said Catherine Turcer, executive director of Common Cause Ohio, a member of the Fair Districts coalition.

Under the congressional map in place since 2012, the Dayton region includes part or all of three U.S. House districts:

· District 1, held by Chabot, covers Warren and part of Hamilton counties.

· District 8 covers Butler, Clark, Darke, Miami, Preble and part of Mercer counties, and is held by Republican U.S. Rep. Warren Davidson.

· District 10, which includes all of Fayette, Greene and Montgomery counties, is held by Republican U.S. Rep. Mike Turner.

In the map the Supreme Court overturned:

· District 1 includes Warren County and a U-shaped chunk of Hamilton County.

· District 8 includes Butler, Darke, Miami and Preble counties, the southern end of Shelby County and a north-central part of Hamilton County.

· District 10 includes part of southern Clark County and all of Greene and Montgomery counties.

In the map created by Paul Nieves, a New York resident who works with the Princeton Gerrymandering Project,

· District 1 would be wholly contained in Hamilton County.

· District 8 would cover Butler, Darke, Preble and Warren counties, a strip of eastern Hamilton and the northwest corner of Clermont County.

· District 10 would remain “almost identical” to the overturned map, Nieves said, covering Greene, Montgomery and part of southern Clark.

The now-overturned congressional map would have likely created 11 Republican seats and four Democratic ones, Nieves said. His proposal would result in eight Republican seats and six Democratic ones. One of those Democratic seats would likely be District 1, a change resulting from keeping minority communities in one district instead of “cracking” them three ways, Nieves said.

Currently Ohio is represented by 12 Republican and four Democrats.

Turcer said she has to assume mapmakers have already been meeting behind closed doors and will rush through the public portion of the process. But voters’ approval of the 2018 constitutional amendment shows that Ohioans expect better, she said.

Turcer predicted the task may revert to the redistricting commission, and that any resulting map may face further court challenges.

About the Author