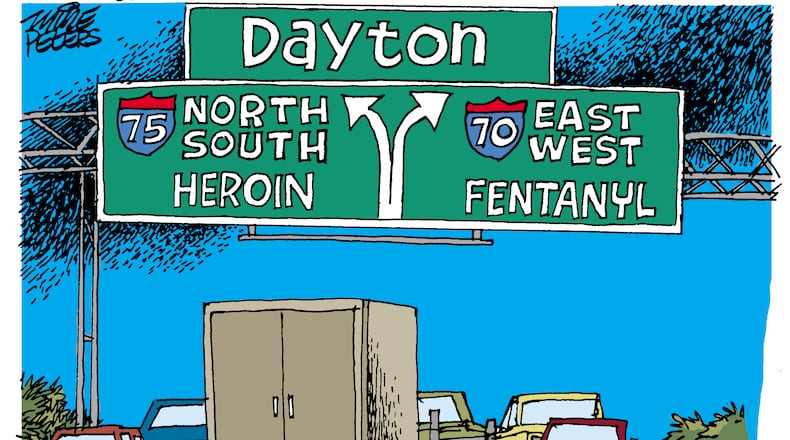

One area heroin user participating in a state study last year said on a scale of zero to 10, the drug’s availability locally was a “15.”

“It’s off the charts easy,” the participant said. “Because 70 and 75 are right there and Dayton is five minutes away.”

» RELATED: Local drug trade ‘bigger problem than we thought’

Law enforcement, treatment providers and drug users say it’s none-too-surprising that Montgomery County is awash with opioids, partly for the same reason the region is attractive for corporate distribution centers.

Credit: DaytonDailyNews

Dayton straddles two major trade corridors, the Atlantic Corridor and the Central Eastern Corridor, and is near the country’s median center of population, according to the local trade group Dayton Logistics. More than half of the U.S. population lives within 600 miles of Dayton.

Overdoses frequently occur in parking lots and businesses just off the interstates. Some don't even make it to an exit.

By the end of May, Montgomery County already had more overdose deaths than the 349 in 2016, itself a record year. Authorities are bracing for 800 deaths this year.

Heroin and now much stronger fentanyl are brought directly to Dayton in bulk by Mexican cartels, said Capt. Mike Brem, commander of the Regional Agencies Narcotics & Gun Enforcement Task Force. The price is so low in the Miami Valley because the drugs aren’t brokered every step of the way, he said.

“We have that (interstates) 70-75 connection,” Brem said. “We’re a source city.”

Seven or eight years ago, someone from Dayton might have gone to Columbus, Cincinnati, or even Chicago or Atlanta, to get a discount on a bulk quantity of drugs, Brem said.

“Now it’s Dayton. It comes from the border to here,” he said. “There’s no taxing it along the way.”

Andrea Hoff, director of prevention and early intervention for the Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services board of Montgomery County, said the county studied why the opioid problem here was worse than other parts of the state as far back as 2010.

Two factors stuck out, she said: widespread job losses following the Great Recession and cheap drugs made more accessible because of the intersection of interstates 70 and 75.

About the Author