“It seemed like leadership was really willing to be vulnerable and talk about themselves and their own struggles, their own difficulties and how they sought help and how it’s an ongoing continued process,” said Maj. David Tubman, director of Clinical Health Psychology, 88th Medical Group.

Tubman, a board-certified psychologist, said Col. Thomas Sherman, 88th Air Base Wing and installation commander, provided an invaluable example to the people under his command, especially those who may be hurting the most.

As part of his commander’s calls, Sherman and his wife, Laurie Sherman, told their “Tale of Two Deployments.” The two shared their experiences by comparing Col. Thomas Sherman’s command deployment to Iraq and another command deployment to Afghanistan some years later.

According to Laurie Sherman, at the time of Col. Thomas Sherman’s deployment to Iraq, the two were newlyweds who had previously had a long-distance relationship, so communication was already a huge part of their relationship.

His deployment to Iraq challenged how they normally communicated. Eventually, they experienced a breakdown and some disconnects in their communication during the deployment and it continued even after Sherman returned. Neither knew what to really expect during or after the deployment.

According to Col. Thomas Sherman, they both realized something was different, but they did not want to reach out for help over concern that the stigma of seeking mental health assistance would hurt the then Air Force major’s career. Instead, they did their best to manage the experience, but it remained something “packed up tight.”

When his deployment to Afghanistan came around, the Shermans realized they needed to use a different strategy to help with the communication issues they previously faced.

Laurie Sherman mentioned that Col. Thomas Sherman, who was a lieutenant colonel then, promised to write her a handwritten letter each day. Some days the letters were detailed accounts of what he had experienced, while others simply said, “I’m exhausted, but I love you.” She said the letters gave her a better understanding of what he was going through.

Col. Thomas Sherman said when he returned home, the effects of combat stress began to manifest, and they did not want to repeat what they had experienced following his deployment to Iraq. After meeting and learning about others facing similar challenges post-deployment, they reached out for help to get in touch with what would become their new normal.

The Shermans encouraged each other to stick with the methods they decided on and said they felt those methods helped them to come through the Afghan deployment stronger than the deployment to Iraq that they experienced.

Tubman said that he liked how Col. Thomas Sherman realized he needed to establish a “new normal” for his life.

“I tend to use that language more often than I use the word resiliency because I think it reflects this idea that when we go against difficult life circumstances that we change along with it,” added Tubman. “There are ways to change for the better, sometimes, when we go through difficult circumstances, and certainly, there are ways we can change, and it can be worse.”

A troubling increase in suicides among Airmen prompted Air Force leaders to reach out to commanders across the Air Force and take notice of not only the numbers, but also the whole impact that each suicide makes on the Air Force’s mission and the families, communities and nation it serves to protect.

“I honestly have never liked the association of our Airmen with being some statistic,” said Chief Master Sgt. Stephen Arbona, 88th ABW and installation command chief master sergeant. People are not statistics; they are someone’s co-worker, friend, son, daughter, sister, brother, wife, husband, father or mother …”

“Our people, all of our people, matter to us as a military and as fellow human beings,” added Arbona.

September is Suicide Prevention Month. National Suicide Prevention Week is observed Sept. 8-14, and World Suicide Prevention Day was observed Sept. 10.

“Everybody goes through trials and tribulations at various points in their life, and it’s OK to not be OK,” said Arbona. “Everyone needs help at some point in time or another.”

“I also hope people realize that just because they seek help, it does not mean they cannot still have a successful career in the Air Force or in life in general,” added Arbona.

For suicide prevention and intervention tools and resources, go to https://www.resilience.af.mil/.

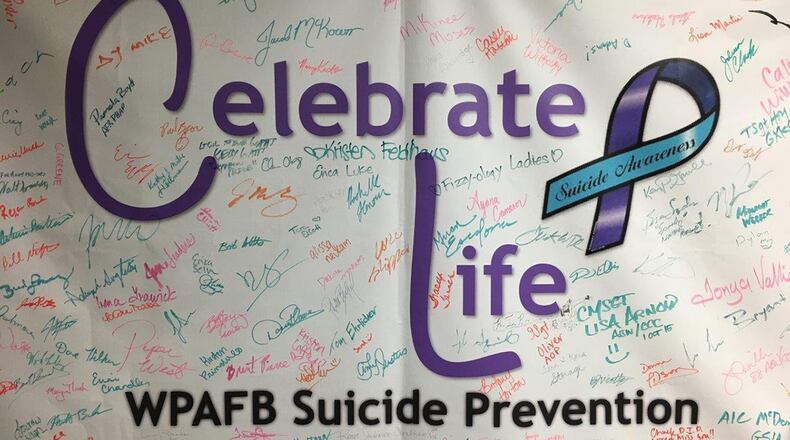

WPAFB held a Resilience Tactical Pause Sept. 5, so that all Airmen and their civilian counterparts could focus on resilience and suicide prevention discussions. (U.S. Air Force graphic)

About the Author