Over glasses of red wine and dinner, Boehner cracked jokes and thanked those who had rallied to him in a lost cause. And while one of those who attended the dinner insisted “it wasn’t a wake, it was a celebration,’’ a former House Republican staffer said, “When you get beat for a leadership post, you go away and that’s it.’’

But Boehner had no intention of going away. Beneath the light-hearted veneer on that evening, the methodical Boehner already was preparing a meticulous plan to return to the peak of congressional power.

Now more than a decade later, Boehner has clawed his way back from the abyss and capped off an improbable comeback.

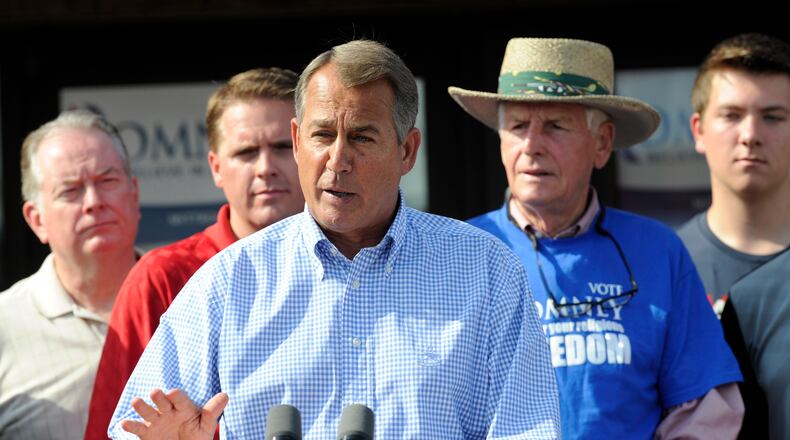

Through the combination of a tenacious personality, relentless ambition, a talent for raising campaign money, and a salesman’s gift for persuasion, the West Chester Twp. Republican has emerged as speaker of the House, only the third Ohio lawmaker ever to occupy the post.

Boehner plans to reform the House

In his speech to the House Wednesday, Boehner made clear he plans to use his new post to reform the House, reducing the power of the speaker to dictate how each bill will be drafted and to make it easier for lawmakers in both parties to have a say in crafting a measure.

“He could have walked away,’’ said former Republican Congressman David Hobson of Springfield. “He did something most people didn’t think he had the capability of doing: He become a very good legislator. Some people are destroyed by defeat. But he didn’t allow that defeat to destroy him as a legislator.’’

Steve Elmendorf, a onetime top aide to former House Majority Leader Dick Gephardt, D-Mo., said that “anybody who gets to be the top leader in their party doesn’t get there by luck. They get there because they work hard and the members respect and elect him. You’ve got to give him credit for getting the job and particularly after coming back after being deposed.’’

To many Democrats and a number of analysts, Boehner’s comeback is a bit too inexplicable. When the Republicans controlled the House during the late 1990s, he was lightly regarded by many commentators who saw him as a mediocre legislator with an indifferent work ethic.

“He’s a country club Republican” who is “always at the country club,” sniffed one former House Democrat, who asked not to be named, while former Republican Congressman Joe Scarborough said last June on his MSNBC television show that “so many Republicans tell me this is a guy that is not the hardest worker in the world. Every Republican I talk to says John Boehner, by 5 or 6 o’clock at night, you can see him at bars.”

Those same critics say he also is the unlikeliest of reformers. Too slick, they say, too close to lobbyists, too addicted to golf, too lucky and too interested in having a good time. A guy who cries anytime he talks about growing up in southwestern Ohio. And what’s with that year-round tan?

They point out that, for two decades in Washington, he has been the quintessential insider, raising huge sums of money from business groups, once appalling critics by passing around tobacco-lobbyist contributions to GOP colleagues on the House floor just before a vote.

He also has the reputation of being a sharp-edged partisan. He is one of the few lawmakers to take a political opponent to court. Boehner sued Rep. Jim McDermott, D-Wash., charging that he leaked to The New York Times a transcript of a cellular-phone call Boehner made in 1996.

“He’s always underestimated,” said Rep. Pat Tiberi, R-Ohio. “Part of it is his style. He doesn’t have a hair out of place, his tie is perfectly tied. But that doesn’t mean he doesn’t have the work ethic of a rugged linebacker, because he does.”

1998 defeat a blessing in disguise

In the heady days of the 1994 Republican revolution, Newt Gingrich’s rise to speaker and just four years after he was elected to the House, Boehner was elected to the No. 4 post in Republican leadership. But after Republicans lost five congressional seats in 1998, unhappy conservatives demanded a change in leadership and they focused their anger on Boehner.

In a post-election closed door meeting on Capitol Hill, Republicans toppled Boehner by a vote of 121-102. As he and his staff walked through the Cannon Office Building corridors to return to his office, Boehner said to no one in particular, “This could be the best thing that’s ever happened to me.”

In a 2001 interview, Boehner said that “you have to understand, I’m an optimist. I can see the brighter side of any human being or any event. Sometimes, you just get dealt a bad hand. So, you just have to accept it and move on.’’

Within a day of the dinner at the Washington restaurant of Sam and Harry’s, Boehner was ready to chart a course back. He outlined some ideas to his top aide, Barry Jackson.

“Let me do a little work,’’ Jackson told him.

The next week, Jackson flew to Cincinnati with an 11-page, single-spaced memo and met with Boehner at his home in West Chester Twp .

As a first step, Jackson recommended that Boehner quickly schedule a series of public events in Cincinnati. In his confidential memo, Jackson wrote that “we need to end any speculation that you are quitting…. People should know you have not forgotten how to be a ‘regular’ congressman and that you take that role very seriously.”

Next, Jackson wrote that “if we are to reclaim our position in leadership, we must repair our reputation with the national media and, in particular, national commentators.”

Jackson pointed out that while national news organizations had reported favorably on Boehner in the mid-1990s, by 1998 it was “common knowledge’’ among reporters that “you were incapable of being elected speaker and were, indeed, the weakest member of leadership.”

And finally, Jackson wrote that “high-profile legislative initiatives are vital to our success.’’ In blunt language, Jackson was telling Boehner he had to prove to Republican members that he could write and pass a law.

In 2001, Boehner took the consolation job of chairing the education committee and quickly got a break: President George W. Bush pressed for passage of a landmark education bill known as No Child Left Behind, and Boehner’s committee had to write the measure.

Forming a businesslike relationship with Democrats George Miller of California, Boehner helped win passage of the bill, prompting former Boehner aide Terry Holt to say that “his comeback was established when the president signed No Child Left Behind.”

In 2006, he scraped together the votes to become majority leader, replacing Tom DeLay of Texas, an implacable opponent who had engineered Boehner’s 1998 defeat. While the Republicans lost the House in 2006, they retained Boehner as minority leader.

Boehner’s style to be drastically different

Now as speaker, Boehner will present a dramatic change in style and substance from former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif. She is the daughter of a powerful political family in Maryland, and later won a House seat in San Francisco, while Boehner was one of 12 children whose father owned a tavern in Cincinnati.

A fervent environmentalist, Pelosi banned smoking in the speaker’s gallery, where lawmakers chat with reporters. Boehner, a chain-smoker who has never met an environmental regulation he seemed to like, found the ban an annoyance.

When Pelosi expanded the menu in the House cafeteria to include foods such as jicama, Boehner quipped, “I like real food — food that I can pronounce the name of.”

Yet he claims to have a cordial relationship with Pelosi as long as they avoid policy -— then, “it’s just oil and water,” he said.

But in substance, Boehner is pledging sweeping changes from Pelosi’s rule. Calling the past four years “an abomination” and complaining that there are “about five people who control the whole process from beginning to end,” Boehner said he wants all lawmakers to have a greater say.

“If we’re able to do this, it will bring the temperature down in the institution,” Boehner said in an interview last October in his West Chester Twp. office. “It’ll begin the process of healing an institution that is broken. It will go a long way in breaking down the scar tissue that’s been built up between the parties and … created by both parties.”

Boehner’s ambitious plan to remake the House draws skepticism among people who have watched Pelosi, DeLay and former Speaker Gingrich centralize power in the leadership offices.

“You can start off as a nice guy, but if you are in charge, you have to run the place, and by definition you run roughshod over the minority,” Elmendorf said. “Because of the nature of politics, we’re past the point where committee chairs get to do what they want.”

Boehner has a very simple reply: “We’ll see…. I say what I mean and mean what I say.”

About the Author