Here is what he remembers from Jan. 6, 1945.

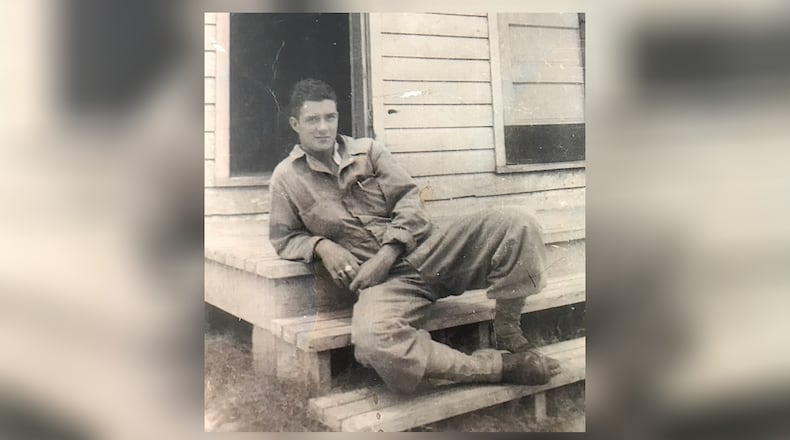

It was during the Battle of the Bulge, the bloodiest conflict for U.S. forces in World War II. He was a 20-year-old gunner in a Sherman tank with Task Force Lovelady, a revered combat unit in the U.S. Army’s 3rd Armored Division.

In the heavy snow and bitter cold, they had come upon a small Belgian town that had been in German control.

Stitt said his tank’s commander, Sgt. John Fasulo, was standing directly behind him. Although sometimes gruff, Fasulo had been collecting lidded German beer steins he found in the wreckage of war and had three of them stuck behind the radio. He planned to bring them back home to Louisiana.

“We were the last tank coming into town, and we had eight young infantrymen accompanying us,” Stitt said as he sat in his Springfield home the other day.

“They were fresh from the States. Really innocent. It was their first day in combat, their squad leader had been killed, and they had no one telling them what to do. I felt sorry for them.

“We drove over a low rock fence, and a German stood up in the grass and fired a bazooka and hit some of the infantrymen. Instead of shooting him, they were yelling at us, ‘There he is! There he is!’

“I could see him, but I couldn’t get our cannon over far enough to shoot him.”

The German fired his Panzerfaust anti-tank weapon a second time, and the shell ripped through the tank as Stitt was leaning forward, looking into the gunner’s periscope.

“It hit right behind my head and killed Sgt. Fasulo,” Stitt said quietly. “He slammed his hands into my back and then fell down on me and then onto the floor. We got out of the tank and were under small arms fire.

“We got into a house and tried to patch each other up. The back of my head felt cold and I reached back and there was nothing but blood. A lot of shrapnel was stuck in my head.”

Under more fire, they finally escaped into a woods and were rescued, and Stitt was rushed to a field hospital.

It was the second time in four months of combat that he’d been wounded, and that brought him his second Purple Heart.

Fasulo was his fifth tank commander and the second one killed alongside him. A third commander had suffered a severe leg injury from a German shell, and a fourth — who’d just spent four months in the hospital with severe burns suffered on D-Day — had a mental breakdown.

And yet, when Stitt recounted his deadly encounter in one of the 82 letters he wrote during World War II to his mother back on Kruger Street in Elm Grove, West Virginia, he simply told her that, should she hear he’d been wounded, she should know his head just happened “to get in the way” of a little shrapnel.

Sometimes those wartime letters fell victim of Army censors. Often, though, Stitt withheld information himself to spare his mother more worry.

Other times, his personal censorship was to spare himself embarrassment.

In one of his first letters from basic training at Camp Polk in Louisiana, he wrote: “I just got back from the movies.”

He laughed at the memory: “That’s all I said. Actually, it was one of those sex movies they show everybody in the service, telling you how to avoid gonorrhea and syphilis and all those things. But you don’t want to write home and tell your mother: ‘I went to the sex movie.’”

What was in his letters and what didn’t make it into print are part of a book that Stitt — an amazing nonagenarian blessed with good health, a sharp memory and quick wit — is putting together with the help of his daughter, Beverly Rutan, who lives in Springfield.

They’ve been working on the project three years and are nearly done.

It’s an effort, they say, that came out of the blue.

Until a few years ago, neither Stitt nor anyone else knew his mother, Ruth, saved all his letters and stored them in a Jane Parker hat box she’d gotten from her older sister, Hattie.

When Ruth died, many of her belongings went to Walter, who stored and forgot them in the South Bend home he shared with his wife, Betty.

After Betty died of ovarian cancer, and later, after another companion died from coronary issues, Stitt was convinced by Beverly to move to Springfield, which is also near other family.

And Stitt knows the area. He graduated from Wittenberg University and Hamma School of Theology in Springfield and later pastored two Lutheran churches in Springfield. Betty taught school in New Carlisle

Stitt now lives in the Forest Glen senior living facility north of Springfield. Throughout his independent living villa, you’ll find remembrances from his war days.

A small box holds the prestigious National Order of the Legion of Honor pin — the highest recognition of French merit awarded to military and civilians — which he was given for helping liberate France from the Nazis.

In a back room, in a frame, is one of the pieces of shrapnel surgeons dug out of his skill.

Over the years he’s made many trips to Europe — at least 27 to England alone, including one just two months ago — and he’s also visited some of the towns he fought in throughout France, Belgium and Germany.

At two separate Belgian towns, appreciative villagers gave him gifts: A replica tank in one place and, at another, a wooden diorama he now displays in his living room.

Across the top, it says: “Thank you for our freedom.”

‘We knew what our job was’

After graduating from Triadelphia High School in Wheeling, W.Va. in 1942 and briefly driving a truck delivering Nehi grape soda, Stitt enlisted in the Army. He spent a year of training at Camp Polk and then boarded the Queen Mary for Europe, arriving in Scotland on June 6, 1944 — D-Day, the Allied invasion of France.

A month later, he was on Normandy’s Omaha Beach.

Told to dig a foxhole, he briefly questioned the need, only to get the deadly answer that night when a German bomber dropped its payload on them and several men were killed.

“In the beginning I had no realistic idea what could happen,” he said. “I was still a bright-eyed, bushy-tailed kid, and we all thought once we got in that American-made steel tank, we were invincible. It’s only after we lost a few tanks and several people that we began to realize maybe the Germans knew something, too.”

When he got into a tank that was freshly painted white inside, he thought he was in a brand new vehicle.

Afterward he learned the truth: “When a shell hit anyone in the tank, their head exploded and there was blood over everything. They’d take it back, paint over the blood with white paint and get replacements for the guys killed.”

His was one of the first tanks to get through the Siegfried Line, Germany’s defensive system along its western border, but on Sept. 19, 1944 his tank was hit by a German shell.

He was a loader and was bending down to pick a shell up when the explosive ripped through the tank, killing the gunner and the commander. The pair fell dead onto each other. They blocked the turret, and Stitt couldn’t move them.

He was trapped until he spotted the driver’s hatch was open. He dove through it, but the impact with the ground slammed his shoulder out of joint. He yanked it back in, tripped on barbed wire while running and tried hiding in a partially dug fox hole as shells exploded midair above him. That’s when he discovered he had shrapnel in his leg.

He finally hobbled to safety, got bandaged up and was back in action with a new crew and tank in less than 24 hours.

“We knew what our job was,” he said. “It was what we’d trained for. We knew people were going to get killed and we saw people killed, but we weren’t going to turn and run the other way.”

Yet, he admitted it first had been hard to pull the trigger and know you were going to kill someone — “it’s not how we were raised,” he said — but he soon learned it’s them or you.

That message was made painfully clear one day when he was sitting with his feet dangling in a foxhole and was handed a letter from his mom.

She’d sent him a newspaper clipping telling how his best friend from home — U.S. Marine Bill Meghan — had been killed fighting in Saipan.

Although the news numbed Stitt — in later years he visited Meghan’s grave at a military cemetery in Hawaii — he said he couldn’t dwell on the loss when he was trying to stay alive himself.

And that wasn’t easy.

There was an incident in which his tank was blown up in a mine field and another time when, as his tank lagged behind because of difficulties, the four other tanks in his platoon were destroyed by the Germans and several of his fellow soldiers were killed.

After he was wounded a second time, doctors assessed he was suffering battle fatigue, and his combat days were done. He recovered in England and was managing a beer hall just as the war in Europe came to an end.

“I’ll be truthful, when I think about it all now, I’m amazed I survived,” he admitted.

Finding a calling

“I was through a lot of hell,” Stitt admitted, and maybe that’s why he eventually shifted his focus toward heaven.

When he was 35 — already married eight years to Betty with three young children — he felt a calling to the ministry.

When he’d first gotten back from the war, he’d spent some 18 months at Marietta College, but he ended up dropping out and eventually was selling Formica in Indianapolis.

That’s the job he left to attend Wittenberg and Hamma.

But during that time the family suffered a terrible blow when middle son, Billy — a 7-year-old first-grader at Jefferson Elementary who was anxious to show his mom one of his school papers — ran from school onto McCreight Avenue and was hit and killed by a truck.

The personal loss, the lessons of war, the life experiences, they all gave Stitt an added depth in his ministry, and for 41 years he served as a Lutheran pastor, first in Louisville, then for a long time in South Bend and twice for shorter stints at Springfield churches: St John’s and First Lutheran.

Over the years he and Betty became world travelers, making dozens of trips to Europe and elsewhere.

They twice visited the Normandy American Cemetery at Colleville-sur Mer in Northeastern France that honors American troops who died in Europe during World War II.

Along the way he’s had some poignant encounters.

He told of German SS solders who came into one French village during the war, rounded up all the women and children in a barn and shot them.

A mother fell dead on top of her 2-year-old daughter. The little girl, covered in her mother’s blood, lay still, and the Germans thought she was dead, too.

“She was the only survivor,” Stitt said. “When I came back 50 years later, I met the woman who had been that little girl. It was amazing.”

Since returning to Springfield, he’s stayed active: Sunday is church, Tuesday is Kiwanis meetings and Fridays are Happy Hour at his senior center. He still drives during the day, takes daily walks, cooks his meals and keeps sharp with crossword puzzles.

The book has kept him — and Beverly — especially busy.

“My dad never really talked about his war experiences, so I didn’t know what he went through,” said Beverly, who encouraged him to write the book.

He’s come up with a remembrance where some stories are funny, some are poignant and a few detail events that were heartbreaking and, as Beverly put it, “just horrible.”

And then there’s his memory of V-E Day — May 8, 1945 — when Germany unconditionally surrendered to the Allies, and celebrations erupted around the world.

Stitt had gotten a pass and gone to London.

“I moved out of Piccadilly Circus where the crowd was and went over to Leicester Square,” he said. “In peacetime that’s where all the theaters were, where you saw all the movies.

“For five years there had been a blackout, but that evening, all of a sudden, they turned all the lights on. A woman standing next to me was holding her little boy’s hand — he was just 4 or 5 — and she started to cry.

“And next thing, I was crying right alongside her.

“The feeling just overwhelmed you. No more bodies being shipped back. No more bombs. No more running down in air raid shelters.

“Nobody was going to get killed anymore.

“It was just a very moving experience.”

And now, thanks to the man of letters, we all soon will be able to experience it.

About the Author