Holmes is in contention for four different national player of the year awards.

Then on Wednesday, Obi Toppin — the high-flying former Flyer who was the National Player of the Year five seasons ago — met former UD teammate and best friend, Jalen Crutcher, in an NBA matchup in Indianapolis.

Toppin, a former first-round draft pick, plays for the Indiana Pacers and Crutcher, who toiled three years in pro basketball’s minor leagues, just made the New Orleans Pelicans roster.

Their feel-good reunion was watched by several UD fans, as well as Flyers coach Anthony Grant and his assistants, who made the trek to Gainbridge Fieldhouse and embraced the pair after the game.

But the most important recognition of a UD player took place over the past three days on the UD campus and especially Wednesday night at a communal gathering in Kennedy Union.

That’s where Roger Brown — arguably the greatest player ever to wear a Flyers’ uniform and certainly the most unfairly targeted — was sincerely and significantly remembered after having been forgotten, and in some instances purposely ignored, for over half a century.

Jessica Luther, an author, podcaster and especially an investigative journalist of considerable note, was on campus from Tuesday through Thursday as the second-ever Roger Brown Writer in Residence in Social Justice, Writing and Sport.

The first Resident was Wil Haygood, who was here in 2019.

His book, Tigerland, was the non-fiction runner up for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize a year earlier and that, along with so much of his other work dealing with social justice issues, made him a perfect candidate to stimulate thought and conversation among students and community members.

Although meant to be an annual affair, the residency was interrupted by the COVID pandemic until this past week.

As UD president Dr. Eric Spina — the person who is most responsible for Brown finally getting his due — noted Wednesday night before Luther spoke to an audience of UD faculty, students, and community members:

“That didn’t diminish our commitment to continue to honor Roger Brown.”

That was evident by Luther’s inclusion in the program.

She has written extensively on sports and gender violence and specifically helped investigate and expose the sexual assault scandal involving Baylor football players that was covered up by many at the school. Among other exposes, she also has written on the sexual harassment and assaults at Louisiana State University and the toxic culture that existed in the Dallas Maverick’s workplace.

While Haygood’s presentations dealt mostly with issues of race and justice — a topic UD will continue to mine — the impact of Luther’s work is “profoundly important” Spina said:

“We want to make sure we’re addressing social justice of all kinds. We want people to understand it’s social justice writ large.”

Luther spent three days talking to various classes — from gender study to health to journalism — while also meeting with faculty.

She also managed to make a trip to UD Arena — she sat near the Red Scare students and enjoyed the raucous support they gave the team —– and saw the Flyers rout Davidson.

‘Sky was the limit’

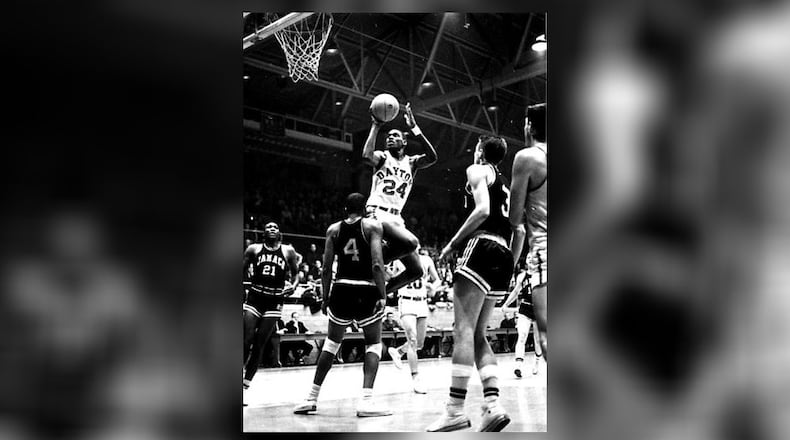

Whatever Luther saw on the court Tuesday night, she could have seen the same — and more — back in the 1960-61 season when Brown was the jaw-dropping sensation of the Flyers freshman team.

It was a time when first-year players weren’t allowed to play varsity, but that didn’t matter. He was the biggest hoops draw in town.

“The sky was the limit for this guy,” Ted Green, the producer of the documentary, “Undefeated” The Roger Brown Story,” said in a special video on the UD Residency that Spina wanted the Kennedy Union crowd, especially the students, to see.

“(Roger) and Connie Hawkins were really looked upon as the two best high school players in the country coming out in 1960,” Green said.

Brown not only starred on the court and was beloved by his teammates, but he attained hero status in the community, especially in West Dayton, which had seen very few black players up to that point wear a UD uniform.

But in 1961, Brown was unjustly pushed out of UD because his name was thinly linked to a gambling scandal that rocked the college game that year.

When he was a teenager on a New York City playground, he had been befriended by couple of hoops-junkie gamblers, Joe Hacken, and especially former NBA player Jack Molinas, once the roommate of UD’s Monk Meineke.

Brown’s only sins — and they were as a teenager — appear to be that he used Molinas’s car and accepted $200 to introduce Hacken to other playground ballplayers.

None of those he introduced — nor Brown himself — was ever found to have fixed games, bet on games, or done anything improper from their associations with Hacken or Molinas.

Brown was not in contact with either man once he got to UD.

When Brown’s name surfaced in traffic court because he once had been in an accident in Molinas’s car, the NCAA got interested and UD — which had paid for Brown’s trips back to court, an NCAA no-no — reacted quickly and dropped him from the freshman team and dismissed him from school.

It was done to help lessen any sanction that might come from the NCAA.

The NCAA then banished Brown, as did the NBA, which later would pay a huge settlement for its unfair actions.

“Picture Mr. Brown, far from home, a young man in a racially-segregated town during a period fraught with racial tensions and great towered differentials,” Spina said in the video.

“It literally makes your heart ache to consider how alone he must have felt and indeed how alone he must have been. His dreams of a college degree and a pro career – both were dashed.”

“He was devastated,” said Bobby Cochran, who played industrial league ball with Brown afterward. “All he wanted to do was to come back to UD and play ball.”

Brown ended up working at Inland and for six years played on various AAU and industrial league teams that called the Fairgrounds Coliseum home. That’s where he was befriended by guys like Cochran, Ike Thornton, and Bing Davis, who is now a nationally acclaimed artist and a local treasure.

Brown also had a set of guardian angels in the late Azariah and Arlena Smith who took him under their wing — they had no children ― and let him live in their Shoop Avenue home.

Arlena once told me how Roger, racked by nightmares, would wake up at night crying: “I didn’t do anything! I didn’t!”

Years later, thanks to a push by NBA great Oscar Robertson, the Indiana Pacers of the American Basketball Association (ABA) drafted Brown and he became an All Star for them.

After his playing days, he became a respected civic leader and politician in Indianapolis.

In 2013, 16 years after he had died from liver cancer, he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

“Even though he resurfaced and became a star again, he still lost what were probably his best years,” said Green. “And, more importantly, I think he lost some of his soul; he lost some of his dignity; and he lost some of that sweet disposition.”

Just before he died, I interviewed Brown, who had trouble breathing and speaking that day.

I still remember the raspy embrace he gave the school that had wronged him.

“I loved being a Dayton Flyer,” he said quietly. “I loved UD…I still do.”

‘That was neither right, or just’

UD shouldn’t bear all the blame for what happened to Roger Brown.

The NCAA made him a teenage scapegoat and the NBA followed suit.

And both of the Dayton newspapers that covered the team back then — the Dayton Daily News and the Journal Herald — were complicit as they presented a one-sided narrative.

When Spina — who was raised in Buffalo and came here from Syracuse University — took over the UD presidency in 2016, he soon learned of Roger Brown.

Bing Davis played a big part in that, and, after that, Spina met with other people on campus to find a way to right the long-standing wrong.

“Mr. Brown was one of the greatest basketball players ever to attend UD,” Spina said. “Kind and gentle and thoughtful, he was still highly regarded in the Dayton community, but (decades) after his death he remained all but invisible at the University of Dayton.

“That was neither right, nor just.”

From that came the first Roger Brown Writer in Residence in Social Justice, Writing and Sport.

“This exceeded all our expectations,” Bing Davis said in the video. ‘It’s an outstanding educational experience that’s going to last forever.

“I think (Roger) would be extremely pleased and happy with all the possibilities of what this does. It goes beyond just recognition. It honors an athlete in a positive way that’s going to add knowledge and wisdom and understanding to the community and the students, while it also addresses social concerns.”

As Haygood summed it up:

“It’s a wonderful comeback story. It’s also a wonderful lesson for students.

“It’s a gift that Roger Brown has now given us all.”

About the Author