He was tall and quick and many figured one day he’d make his name in sports.

“I remember one day in fifth grade, I stood up in front of all my peers and friends who just assumed I’d be the next athlete to come out of the neighborhood and I told them, ‘No, I want to be an artist when I grow up,’” he said.

“That was a big, big moment for me.

“It was me declaring what I wanted to do, rather than my well-meaning friends and family who already said, ‘He’s our next basketball player. He’s our next track person.’”

Even so, he initially did make his name as a hoopster and a sprinter.

At Wilbur Wright High School, he was a two-time All-City basketball player and won Negro All-State honors from the black newspaper, the Cleveland Call & Post.

He went on to play basketball and run track at DePauw University in Greencastle, Ind., and today is in the school’s athletics hall of fame.

Thanks to sports, he was able to get a college degree and make art his life’s calling.

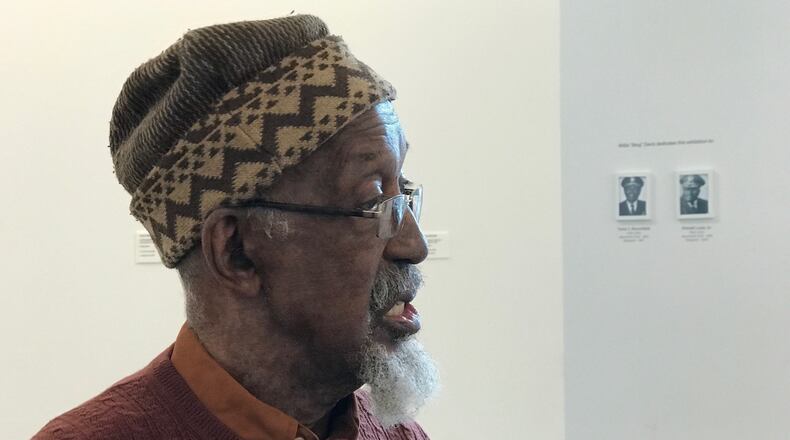

At 84, he’s now an internationally-acclaimed artist and one of Dayton’s favorite sons, a beloved figure, still tall and lean, with an ever-present kufi crowning his head and a tuft of white whiskers clinging to his chin.

And that brings us to today and The Contemporary Dayton gallery in downtown Dayton where his latest exhibit – entitled Kneel – is finishing a 10-week run with a final weekend on display. After that it likely will end up in other galleries around the nation as much of his other work is now.

Kneel – which metaphorically connects the peaceful Colin Kaepernick protests of a few years ago and the kneeling act by a Minneapolis policeman that killed George Floyd – includes a series of kneelers in the found art form that Davis so often embraces.

This time he’s used reclaimed wood and nails and well-worn footballs he got from Dunbar High School, which, when explained, add special meaning.

The aim of the exhibit is to bring up issues like police brutality, endangered youth and communal hope. And the kneelers allow the viewers to actually participate.

On the wall overlooking the exhibit is a quote from Ida B. Wells Barnett, the investigative journalist and civil rights activist of more than 100 years ago, who was one of the founders of the NAACP and is best known for her work documenting lynchings in America:

“I am but one voice through which we tell the story of lynching. I have told it so often that I know it by heart. I do not have to embellish. It makes its own way.”

Since this exhibit – which is dedicated to the two prominent black police chiefs in Dayton’s history, Tyree Bloomfield and Ronald Lowe Sr., both friends of Davis – opened on Nov. 5, a few people have asked Davis about his “protest art.”

He’s also heard: “Oh, I didn’t know you were so angry.”

To each he’s said, “No.”

“This is not protest art, it’s just an extension of what I’m seeing.”

He also said, “I’m not angry. You can’t make art out of anger. You make art out of love. I love people. I love this community and I want to express deeply what I see and feel.”

That said he admitted to being “devastated” by the video of the cop kneeling 9 minutes and 42 seconds on George Floyd’s neck, an act a jury deemed second-degree murder and worthy of a 22 ½-year prison sentence.

“One of the misconceptions we all have about lynchings is that they’re about a rope and tree,” said Michael Goodson, the curator of The Contemporary Dayton. “But they take place in many, many ways.”

Several black men in his community – including some of our best-known athletes and coaches – have stories of runs ins with authorities when they were doing nothing wrong. And many could have escalated with one misconstrued move.

Davis had a harrowing encounter seven years ago when he was returning from being honored at DePauw.

A white motorist with road rage targeted Davis, whom he thought was going too slowly, and called police saying a black man was driving down I-70 waving a gun.

The next thing Davis knew, his vehicle was surrounded by four highway patrol cars and he was thrown to the ground and handcuffed.

There was no gun and no threat and eventually the shaken Davis was released.

That’s when he said he asked a young patrolman what would have happened had he reached into the glove box to get his glasses.

He told me: “I would have shot you.”

‘Art as an agent of change’

Davis was born in South Carolina where his family had been sharecroppers.

Once they moved to Ohio, his dad left the family, which included six kids.

Although Davis’ mom only had a third-grade education, she worked two jobs – as a hotel maid and as a cook at a pair of downtown eateries – and showed she had a PhD in survival and nurturing and love.

Bing’s late brother John once told me how the two of them used to frequent the alleys in their East Dayton neighborhood and look into trash cans.

“I was looking for pop bottles and copper wire, anything I could sell so we had 10 cents for the movies on Jefferson Street,” he said.

“But Bing would be looking little artifacts, broken earrings, anything to use in his art. He’d find pencil stubs and take them home and draw with them.”

And Bing’s mother would iron the wrinkles out of brown paper bags so he had flat paper to draw on.

“There was a lady named Miss Walker who came twice a week to our East Dayton neighborhood and conducted free arts and crafts classes,” Davis said. “I’d be playing 3-on-3 in the gym when she came, so I’d get somebody to hold my spot on the court and then I’d go do arts and crafts.”

Once he was 16 – even though his art and sports careers both were showing promise – he contemplated quitting high school and getting a job to help the family.

“In my neighborhood, like a lot of black neighborhoods here in the ‘50s – males dropped out of school when they were 16,” he said. “They got a work permit and went into the factories – especially the bottling company and the meat packing plant in East Dayton.”

But when Coach Dean Dooley – a guiding force for Davis as was Jack Reynolds, the director of the neighborhood rec center – heard Bing was contemplating dropping out of school, he gave him a directive:

“I thought you wanted to be an artist? You need to go to college to get your degree and sports will help you get there.”

Although Davis was a standout athlete and a good student, he got no scholarship offers.

Dooley eventually got him into DePauw, where he became one of just five blacks on campus.

He excelled in the classroom – later getting his masters at Miami University – and became an educator, teaching first in the Dayton Public Schools system and then at Central State, Wright State and DePauw.

Early in his career he made the revelation that has since has defined him:

“I learned art was about more than just pretty paintings you put on the wall.

“In 1966, I stopped teaching art and began teaching people. I found you could use art as an agent of change and help build better people.”

Found art

As Davis took me through his exhibit the other day, he said: “Almost everything here is a found object from the streets, the highways and the alleys. Other things are everyday items that are repurposed.”

An elaborate mask hanging on the wall that commemorated the hiring of a new police chief included an old tire he’d found discarded on Highway 35 and Maasai-like, urban prayer beads that had been doodads he’d found at Mendelsons.

And then there were the footballs that are central to those kneelers.

“It’s a great concept and I have to thank Michael for that,” he said. “He contacted Dunbar. The idea was to get balls actually used by the boys on the football team.

“Think how many kids held these balls and had thoughts of going to the NFL or playing in college or just making their family proud. Carrying these balls, they sweated and they strained and they dreamed.

“All these footballs now come with an energy and a power to them. One we hope we can tap into. And one you don’t ever want cut short by the things we have remembered here.”

This truly is an example of communal love.

About the Author