On December 4, 1948, the Toledo Central Catholic Fighting Irish — a team, that would finish the season as the big school’s state runner-up — showed up in Ottoville, my small northwestern Ohio hometown, to play our team, the Big Green, which was coached by my grandfather, L.W. Heckman.

Toledo would come to our cracker box gym every now and then for a game on the way to its annual match-up with nearby Delphos St. Johns the next day. Over the years Ottoville held its own against the “city” boys, but not this time.

On that particular night, Agnes Archdeacon, L.W.’s daughter and my mom, was keeping the scorebook as she usually did.

She penciled in No. 10 for Toledo, Don Donoher, a lean junior forward, who ended up scoring eight points and committing two fouls in what would be a 65-40 Toledo victory.

Years after my grandfather passed away, I ended up with the scorebooks from his 30 years as the Big Green coach.

After I returned here to Dayton as the sports columnist, I took that old ledger from the 1948-49 season along with me when I met Donoher for one of the many breakfasts we had together over the years. This one at the Golden Nugget Pancake House.

“Nobody should have been sore at me up there,” he laughed as he perused the scorebook numbers. “Like usual, I didn’t make much of a splash.”

Typical Donoher. Downplaying his efforts.

He was a good enough high school hooper — even playing through serious injuries as a senior — that he had offers to play at several colleges and chose Dayton, where he would be the team captain and MVP his senior season.

He made his real “splash” when he became the Dayton Flyers coach. When he took over the job after the death of Tom Blackburn, he was just 32 and made $186.40 a week.

UD got a tremendous return on its money.

His first two seasons he took the Flyers to the Sweet Sixteen, then came the storybook 1966-67 campaign and a berth in the national title game that put Dayton basketball on the map and electrified the entire city.

The year after that the Flyers won the prestigious NIT and the communal party raged again. In his first seven seasons he took UD to five NCAA Tournaments and two NITs.

Donoher won 437 games over his 25 seasons at Dayton and took 15 teams to postseason tournaments, including another run to the Elite Eight in 1984.

He would be enshrined in the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame, the Ohio Basketball Hall of Fame, the University of Dayton Athletics Hall of Fame, the Toledo Area High School Hall of Fame, and the Toledo Central Catholic Hall of Fame.

More importantly, he would he held with admiration, respect, pride, and unwavering love in the hearts of so many people across the Miami Valley, not just for what he and his teams accomplished on the basketball court, but the way he was off it.

He didn’t like being the center of attention or being singled out and could deflect praise better than DaRon Holmes II swats away opponents’ shots.

He would sidestep the limelight better than Johnny Davis or Negele Knight ever juked a defender.

That’s why, when he returned to UD games after his coaching days were done, he sat unannounced up in the 300 Section seats amongst everyday fans rather than sit courtside where everybody could see him and make a fuss.

His humility, his work ethic, his dedication to the game and the young guys who played under him were evident even when he volunteered to help coach at Bishop Fenwick High School in Middletown after his UD days.

It started when his grandson was playing there, but he stayed on for a decade more because he felt a commitment to the kids and the program.

I remember coming to the Fenwick gym more than an hour before a JV game one evening and there he was in the locker room, writing on, arranging, and studying a stack of note cards that detailed various offenses, defenses, opponent’s tendencies, you name it.

I was incredulous.

Here was a guy who had coached over 700 college games, had coached the 1984 U.S. Olympic team, was on the Indiana bench with Bobby Knight for a season, had been a pro scout for the Cleveland Cavaliers and he was deep in preparation for a nondescript JV game?

He was so intent, so focused that he said he really didn’t have time to talk.

“This game means as much to these kids as all those other games meant to those guys who were playing then,” he said.

And it meant a lot to him. Donoher was never casual, cursory, or half-hearted in his preparation.

He was substance over style, humble, hardworking. He was someone who was about a lot of the right stuff in life. All that made him a solid cornerstone in our community.

And that’s why so many people have been saddened the past couple of days,

Donoher, who’d been dealing with declining health the past several months, died Friday evening. He was 92.

He’s survived by his children — Paul, Maureen, and Brian — and their families. Sonia, his wife of 66 years preceded him in death, as did their son Gary.

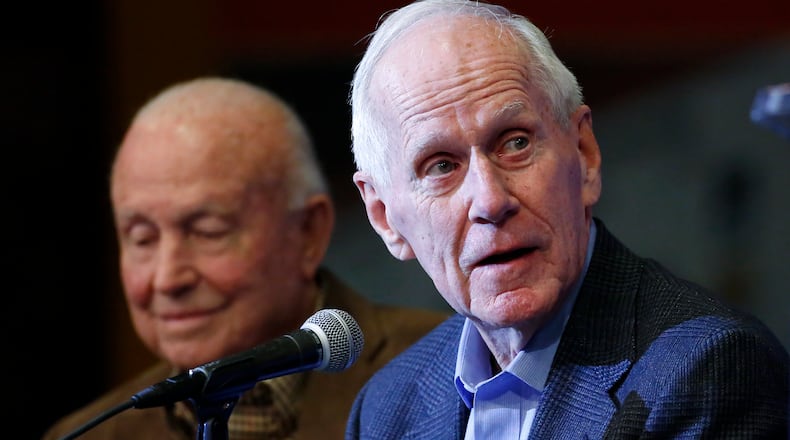

Credit: David Jablonski

Credit: David Jablonski

‘Say hi to Mick’

His last public appearance was at the Flyers’ Dec. 2 game with Grambling State when Brian brought him out onto the UD Arena floor in a wheelchair for a halftime celebration with the rest of that 1984 Elite Eight team.

Flanked by Roosevelt Chapman, the star of that team, and Anthony Grant — Chapman’s freshman backup then and now the Flyers head coach — Donoher got a standing ovation from the sold-out crowd when he was announced.

He smiled and waved, and, throughout the Arena, you could feel the love.

No matter where you went, Donoher was synonymous with UD basketball and its decades of success.

Back in my hometown in the 1960s, Donoher was our link to big-time college basketball. He signed one of our greatest stars — “Big Jim” Wannemacher — who became a 6-foot-6 forward on the Flyers’ team that made it to the national championship game in 1967 and won the NIT a year later.

Tom Heckman, a dead-eye shooter from Glandorf, another small Putnam County town, was on that team, too, and then Steve Turnwald, another standout from Ottoville, joined the Flyers varsity beginning with the 1968-69 season.

I can’t tell you how many times over the years when I was covering college games somewhere that a coach — when he knew I was from Dayton — brought up Don Donoher and what he either meant to him or the game of basketball.

As I walked across the court at Mississippi State some years back, Bulldogs’ coach Ben Howland came up, asked about Donoher, and then talked warmly about him for several minutes.

Credit: HANDOUT

Credit: HANDOUT

The late Rick Majerus, then at St. Louis, stood in the hallway outside the Billikens’ dressing room after a game with the Flyers a couple years before he died and began to weep as he told me how much Donoher meant to him and his family.

He said his ailing mother would always tell him: “Say hi to Mick” when she knew he was coming to Dayton.

Jerry Tarkanian stopped me in a Las Vegas coffee shop once to talk about Donoher. John Chaney did the same as he walked up the steep ramp that led out of UD Arena back to the waiting Temple bus. And after a bombastic press conference once, Bobby Knight pulled me aside and in a true Jekyll-Hyde transformation, asked about Donoher in a tone that showed his affection.

As for Donoher, he had some good stories about some of those coaches.

I’ll share two.

Knight and Majerus

It was during that run to the 1968 NIT title that he first began his association with Knight.

Although Donoher barely knew Knight then, it was tough back then for teams to get videos of opponents they rarely played. And UD faced that predicament when it was to meet Fordham in the second round of the NIT.

“I looked at their schedule and saw they had played Army where Knight was coaching,” Donoher said. “Now the day we’d beaten West Virginia in the first round, Army had lost to Notre Dame and the word around the Garden was that Knight was not a happy camper.

“I’d heard he’d thrown the NIT rep, and the tournament watches he’d brought along with him, out of their dressing room.

“I knew he wasn’t happy, but I figured we were two Buckeyes, so I thought he might listen. I got him on the phone, and he didn’t say much, but he said he could help me out.

“Chuck Grigsby (Donoher’s assistant) drove up to West Point and came back with a detailed report on how we should play them.” UD followed the script and won 61-60.

The Flyers next opponent was Notre Dame and Donoher again called Knight, who was a little short this time, but agreed to help.

Grigsby made the return trip, got the info and UD edged the Irish, 76-74.

That put the Flyers in the title game with Kansas.

Donoher started to laugh as he recounted getting a phone call the next morning from the front desk of his hotel. He was read a note from Knight that he said went something like this:

“Congratulations. I know nothing about Kansas. I assume Dayton is paying you a salary. Maybe it’s time for you to figure one of these things out…”

And here’s a Donoher story on Rick Majerus:

When the 300-pound Majerus was at Utah, Donoher said he lived in a hotel near campus and paid for a prime parking spot at the Huntsman Center, the Utes 15,000-seat arena.

Donoher was visiting on a game night and Majerus told him they’d meet at 6:45 in the hotel lobby. That was just 45 minutes before the tip, but Majerus always let his assistants handle pregame duties and he’d just come in for the final talk.

“It was snowing like hell and when we got to the parking lot some fan had parked in Rick’s spot,” Donoher said. “Well, Rick hadn’t said a word the whole ride over because he was tensed up and now, he goes roaring around the lot until he sees an empty spot behind two orange cones.

“He drives right over them. I get out and try to straighten them up and he yells to leave them. We head toward the arena and next thing I turn and he’s not there.”

Donoher finally found Majerus at his old parking spot, down on all fours, letting the air out of one of the interloper’s tires.

“I was embarrassed and walked way on ahead and it seemed like it took him forever,” Donoher laughed. “Finally, here he comes, and I said, ‘How many tires did you flatten?’

“He said, ‘Two.”

“I said, ‘Why two?’

“And he said, ‘Because the guy’s got only one spare!’”

‘What could be better?’

While Majerus and Knight were two of Donoher’s closest coaching pals, there’s no one in basketball he felt prouder of than Grant, his former player, who just finished his seventh season as the Flyers head coach.

Donoher privately celebrated Grant’s many good times but made sure he was there in the worst of moments, as well.

When Chris and Anthony’s son was stillborn several years ago when Grant was a Florida assistant, Donoher headed straight to Gainesville, just to let them know someone was there for them.

In turn, when Sonia was in a nursing home with fading health, Grant would come to visit and, on occasion, brought along his late daughter Jayda, who Donoher said made both he and his wife smile.

Over the years I did stories on Donoher in the toughest of times, including when he was fired in 1989 after three losing seasons and had to work his way through his own despondency and reclusiveness afterward; and after his beloved Sonia’s death in 2020.

I also covered some of his greatest moments.

When Donoher won the U.S. Basketball Writers Association’s prestigious Dean Smith Award in 2017, some 400 people showed up at a gala community celebration to honor him,

That night, as Grant looked over at his coach, he said:

“I think all of us that had a chance to play for coach know where his heart is.

“We know who he is as a man, who he was as a coach, and what he stands for. All that stuff stays with you for the rest of your life.”

Over the years Donoher had offers from bigger schools, but never entertained them.

“I didn’t see how it could be any better than coaching at my alma mater,” he said “I mean, you got to be kidding. What could be better?

“Sonia’s from here. All the basketball players stayed in town afterward. It was like being in a fraternity. It’s been a great privilege to be a part of the University of Dayton.”

Some years ago, I was working in a flower bed in front of my house on Jones Street in the Oregon District when I looked up and saw Donoher coming down the sidewalk.

“Mick, what in the world are you doing here?” I asked.

He explained how his wife — who was Sonia MacDonald when they started courting — had grown up on Jones Street just a few doors down from where I live now. She had gone to Stivers, was working in a downtown office and living at home when they met.

The house was no longer there — when they put US 35 through downtown many years ago, some of those homes were torn down — but the old memories were still intact.

Donoher told me how he used to have to “hoof it” to get from Sonia’s house back to campus at night to beat Blackburn’s curfew.

“It was about a mile and 35 wasn’t there yet, so I’d turn off Jones Street onto Brown Street and then follow it until I cut off at Alberta,” he said.

So, what was he doing now?

“I just thought I’d retrace that route for old time’s sake,” he said quietly.

He once told me how he’d met Sonia in the fall of his junior year at UD.

He and some of his buddies from the St. Joe’s dorm had gone down to Cincinnati to see the Flyers football team open its season against the UC Bearcats.

“We bumped into a group of Dayton girls down there and we ended up staying over in the same hotel the girls were at,” he said. “Afterward, I was walking around and happened to see Sonia sitting by herself in a banquet room.”

Although he had gotten some fanfare as a sophomore player on Blackburn’s team — he had played in 12 games and had a game-winning basket in one — he was still shy and unworldly when it came to the opposite sex.

“I walked over and managed to say, ‘Hi Sonia,’” he quietly recalled, then smiled. “And she said, ‘Hi Mickey, why don’t you sit down?’

“Well, I did sit down and, as I like to say now, I never got up. It’s the smartest thing I ever did.

“That’s where I belonged. Right there next to her.”

And now, in a few days, that’s where he’ll be again.

He’ll be buried next to Sonia in Section 44 of Calvary Cemetery.

About the Author