“I’m not a crybaby!”

With her, it always was more like the driving motto of Oakland Raiders contrarian, Al Davis:

“Just Win, Baby!”

And win Doris Black did:

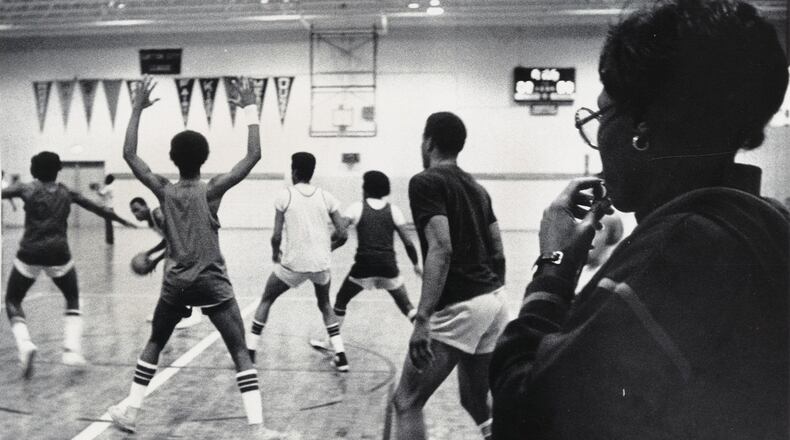

•It’s why she made Dayton history 42 years ago when she became the first female coach of a varsity boys basketball team in the Dayton City League, a feat that hasn’t been equaled since. And by the way, that 1977-78 season, her Colonel White Cougars went 16-5 and won the City League title.

•It’s why she has been enshrined in halls of fame of Central State University, Clarion University in Pennsylvania and the Dayton Amateur Softball Commission.

•It's also the reason the Varsity Club is honoring her Friday night at the TASTE restaurant in Trotwood for her accomplishments, both as a Roosevelt High School athlete and for her championship seasons coaching the Colonel White girls basketball teams and the boys.

The group, which meets once a month to celebrate the accomplishments, mostly athletic, of graduates from the various Dayton public schools and nearby Jefferson High, too, has also named its award to top female athletes at the schools after her.

•Finally, it’s why her legacy – along with those of similar pioneers in the sports/gender debate – will be seen at Sunday’s Super Bowl in the person of Kelli Sowers, the San Francisco 49ers assistant coach who will be the first-ever female coach in the NFL title game.

Four decades earlier – with far less fanfare and, at times, more acrimony — Black was convinced on the fourth try by Colonel White principal Robert Lacy to leave her successful girls program at the school and take over the Cougars’ struggling boys team.

While the players, their parents, the student body and faculty all supported her she said, some opposing coaches did not and they voiced their opinions in the community and sometimes in the newspaper, as well, she said

“They said the job should have been advertised and they should have had an opportunity to apply,” Black remembered. “Mr. Lacy said that since I was already a head coach at our school, it was a lateral move. But some guys thought a man should have the job.

“It’s tough when you read things and you hear things that basically aren’t true. They said I wouldn’t be able to control the guys, that I wouldn’t have the discipline. But I had no trouble in the classroom and I knew the sport and how to coach. I didn’t see the problem.

“Then there were guys who told me right to my face, ‘Well, I’m not gonna let a woman beat me.’ And I’d go, ‘Well, I’m not playing you, my boys are. But if I was, I could probably beat you, too.’”

And when her guys did win, she said there were a few rivals who would not shake her hand afterward: “They’d just snub me and walk on.”

Along the way she’s convinced she ran into a referee or two who had familiar opinions.

“I remember when we played the Roth team with Dwight Anderson. He was good, but I think we still could have beaten them. But my whole starting five fouled out. They called over 40 fouls on us.”

Some of her older brothers would come to the games and saw what was happening, but they let her fight her own battles.

“They just said. ‘Keep your head up high. You’re making us proud. Just go out there and do your job. We know what you can do.’”

They certainly did.

“They let me play basketball and football with them and they’d rough me up, but it only made me tougher and better. Then they’d bring their friends over and have me play them.

“They’d gamble on me and I’d beat their friends and they’d collect. But they never gave me anything the won. After a while I said, ‘Hey, wait a minute. I’m doing all the work out here. I’m the one’s that’s winning.’”

A life in sports

Her mom was from Fort Deposit, Ala. and her dad came from Florida. They moved to Dayton, got blue-collar jobs and raised 12 kids.

To the family, Doris, always has been known as Tudy.

She said Roosevelt back in the early 1960s didn’t have an expansive athletic program for girls so she took part in whatever was offered: volleyball, gymnastics and fencing.

Outside of school, she played AAU basketball and ran track.

Once she visited Central State she said: “I just fell in love with it.” She ran track, played basketball and was on the Marauders bowling team.

Her first teaching job was at Colonel White, where she said she coached girls track and field, tennis and basketball for “six or seven years.” In the second of her two seasons coaching the boys, the Cougars — hit hard by graduation — suffered double-digit losses.

Central State hired her to be its women’s athletics director and basketball coach. After five years there, she moved to Clarion University to coach basketball and eventually won a conference coach of the year honor.

She followed that by building an athletic program at Agnes Scott College, an all-women’s school in Atlanta. Later she became a high school health and physical education teacher and a guidance counselor in Cobb County.

Retired the past 10 years and travelling, doing volunteer work and going to the gym four or five times a week to work out, the 72-year-old Black said she did return a while back to the sidelines.

She coached the basketball team at her church in Stone Mountain, Ga.

The boy’s basketball team.

Proud to set a standard

Friday night’s Varsity Club event — which begins at 7 p.m., is free and open to the public — will honor several people with Roosevelt ties.

John Henderson, who played for the Michigan Wolverines and then spent eight years in the NFL with Detroit and Minnesota – playing with the Vikings in Super Bowl IV against the victorious Kansas City Chiefs – will receive the Outstanding Achievement Award.

The late Al Tucker Sr., who toured with the Harlem Globetrotters, is getting the All Star Legend Award. Educator Lucinda Adams, a gold medal sprinter at the 1960 Rome Olympics, will receive the Coach’s Award. And the 1934 Roosevelt state champion basketball team will be celebrated, as will Joe Madison, the syndicated radio talk show host.

‘I’m excited and humbled that they are recognizing me so long after I’ve left here,” said Black who now lives in Stone Mountain.

She got back to Dayton late Thursday night and, with a little prompting, the memories – especially of those Colonel White days – came flooding back:

“Looking back, I’m proud of what I did, proud that I could set a standard for other women. And now you’re seeing some women get an opportunity in pro basketball and pro football.”

Along with Sowers, Kathryn Smith spent the 2016 season as a special teams assistant with the Buffalo Bills and Jen Welter was the first woman on an NFL coaching staff when she spent the 2015 season with the Arizona Cardinals.

Becky Hammon became the first female assistant in the NBA when she joined the San Antonio Spurs in 2014, a team she’s still with. Kris Tolliver, a three-time WNBA All Star, moonlights with Washington Wizards coaching staff and Jenny Boucek is on the staff of the Dallas Mavericks. Former Cal women’s coach Lindsay Gottlieb is in her first season as an assistant with the Cleveland Cavaliers.

Five years ago, Hall of Famer Nancy Lieberman, who had coached men in the NBA D League in 2009, spent a season with the Sacramento Spurs.

“It makes me feel good that I was a trailblazer a long time ago,” Black sad.

As she thought about those days coaching the Colonel White boys, she started to laugh:

“The gym would be packed. There’d be standing room only. People just wanted to see what ‘that woman’ was gonna do.”

And they saw a lot.

They saw her Just Win, Baby!

They never saw a crybaby.

About the Author