Tromping around Calvary on Friday afternoon after the rains stopped, you could see the brilliant yellow daffodils that lined the entrance, hear the chirping robins continually try to coax spring out of the late-March cold and witness a University of Dayton presence everywhere you looked.

In the distance, to the east, the signature blue dome of the UD chapel on campus stood out. Through the trees to the north, you could see UD Arena down below. And throughout the Calvary grounds, you saw names of people who were associated with U.D. – especially sports figures.

That was evident when I stopped at Section 29 – there are some 46 sections in the cemetery – walked just a few feet from the roadway and came upon the flower-flanked grave of Flyer football player Matt Dahlinghaus.

I was at Doyt Perry Stadium in Bowling Green that November day in 1972 when Dahlinghaus – a Flyers defensive tackle from Chaminade High who had grown up on East Fifth Street – went chasing after the Falcons Paul Miles, who was on an end sweep.

Dahlinghaus got hit and ended up motionless on his back for a long time. The stadium fell into silence. He was eventually rushed to St. Vincent Hospital in Toledo where it was determined he had suffered a severe neck injury, had fractured vertebrae and was paralyzed from the chest down.

Two days later I remember being in the overflowing UD chapel for a special Mass said for him. He would eventually be brought back to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, and had begun therapy only to die from a blood clot in late December. He was just 20.

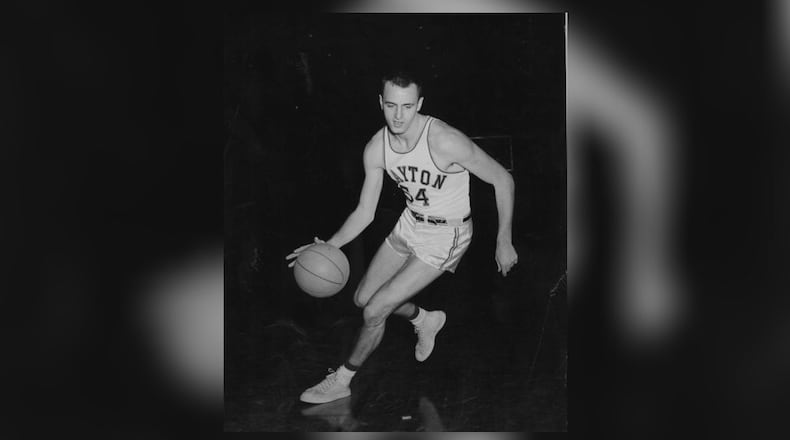

As I was engrossed in those numbing memories, I came upon Monk Meineke’s grave marker. And while it has an NBA emblem on the front – he played five seasons in the pros and was named the NBA’s first-ever Rookie of the Year in 1953 – he’s best known here as one of the most legendary Flyers ever.

“He was Dayton’s first All American,” former UD coach Don Donoher said Friday afternoon. “He was the cornerstone of the program and everything took off from there.”

After starring at Wilbur Wright High, he was playing industrial league ball here when Donoher’s predecessor, Tom Blackburn, made him part of his first recruiting class.

“Blackburn got Monk, Chuck Grigsby and Junior Norris all out of the industrial league,” Donoher said with a laugh. “He signed all of them and it took nothing more than some bus tokens.”

Meineke, who died in 2013 at age 82, remains the sixth all-time scorer at UD, amassing 1,866 points in just three seasons

Between Matt’s and Monk’s graves, just a few rows back, was the marker for Edward Hamant, who played on UD’s first golf teams in the early 1930s, was the Ohio intercollegiate champ and 15 years ago was enshrined in the UD Hall of Fame.

Farther along in the section you come upon the grave on another Hall of Famer, Al Mahrt, who starred in football and baseball when the school was still called St. Mary’s. After serving in World War I, he returned and was the quarterback of the Dayton Triangles, He ended the 1920 season leading the league – the American Professional Football Association which is now the NFL – in passing yards and completions.

On the other side of Section 29, are the graves of former Flyers athletics director Tom Frericks and his wife, Roselyn. A former Chaminade coach from Minster, Frericks was a visionary when it came to UD athletics.

“Tom Frericks was in just his third year as the AD and it wasn’t like he’d come from the Harvard School of Architecture,” Donoher once told me. “He had been a gym teacher and a high school basketball coach. But from the time he took over at UD, he envisioned something beyond the Fieldhouse. He knew UD basketball was getting too big for it.”

The old Fieldhouse seated just over 5,800 and a lot of name schools didn’t want to come in here and play. Frericks tried to make his case, but initially no one listened.

“He was a voice of one,” Donoher said. “There was no support on campus or in town.”

After UD ignited the town by making it to the NCAA Tournament’s national championship game in 1967, Frericks finally had a platform from which to launch his idea.

That produced UD Arena, the glorious gathering spot for Flyers basketball for 49 years now and the host of the most NCAA Tournament games in college basketball history.

None of that is mentioned on Frericks’ grave marker.

The most unique thing is that other side of the tombstone designates the grave of Tony Kramer, Rosie’s brother, who was a former UD player and became a longtime NFL referee.

A unique tour

The first Catholic cemetery was St. Henry’s, located along South Main Street between Miami Valley Hospital and where the old Dominic’s restaurant once stood, said Scott Wright, Calvary’s Community Outreach Director.

Calvary was begun in 1872 and by the end of the century, the graves from St. Henry – overfilled from deaths from epidemic illnesses and the Civil War – had been transferred to it.

Today, Calvary includes 200 acres, 110 which are in use, and some 80,000 graves.

As Rick Meade, Calvary executive director, pointed out Friday: “The number of UD alums here is tremendous. We just have a strong UD connection all the way around. A lot of the folks on our board of trustees are UD grads, too.”

In years past Meade wrestled with ideas of properly promoting the cemetery at UD’s biggest gatherings – its basketball games which draw some of the nation’s top crowds each year.

“I was always hesitant to have any sort of connection or advertisement connected to an entertainment venue,” he said.

“Someone goes to a game to hoot and holler and forget their cares in life. Then what? Suddenly there’s a funeral ad? Maybe somebody was just starting to get over (a loved one’s loss) and all of a sudden that pops up.”

That’s when Calvary came up with the perfect vehicle.

Every home UD game the cemetery sponsors the Honor Guard that brings out the colors before the national anthem.

And each year Calvary also presents its God and Country Service Scholarship to a UD student whose family or themselves have served in the military. Near the end of the season, the award is made at midcourt.

Along with those connections, the cemetery offers a tour of some of its sports figures – those with UD ties and also an impressive array of athletes and coaches who have no ties to the school – that can be done using a GPS hookup that takes you from grave to grave. It also offers information on its website (calvarycemeterydayton.org) .

Some of the other UD Hall of Fame members featured on the tour include: Tony Furst, the UD football legend who played for the Detroit Lions, multi-sport stars Jerry and Gene Westendorf and Lou Mahrt, football players Peter Zierolf and Bob Shortal, longtime trainer Eddie Kwest, football and basketball coach Lou Tschudi and legendary football coach and athletics director Harry Baujan, who was known as “The Blond Beast” when he starred at Notre Dame and then played in the NFL.

“He was Mr. UD,” Donoher said.

He’s in the College Football Hall of Fame and Baujan Field, home of UD soccer, is named for him.

My favorite story about him is the time he sent his biggest football players to rout the white-robed Ku Klux Klan members who were terrorizing the campus in the early 1920s.

The Klan had a large presence in Dayton then. There were parades through the city. Two Klan newspapers were printed here and over 32,000 people attended a Klan rally at the Montgomery County Fairgrounds

A prime target of the Klan was Catholics and, as U.D. history and religious studies professor William Vance Trollinger Jr, found in his extensive research on the subject, the hate group often made forays onto the UD campus to burn crosses and once even set off bombs.

Bajuan got word that a Klan group was going to burn a big cross on a hill overlooking the campus.

The Beast told his players to “take after them…tear their shirts off …and do whatever you want to them.”

The players routed the hooded thugs and sent them running through the darkness.

A wide array of colorful sports figures

There are many other colorful sports figures buried at Calvary who aren’t directly related to UD.

Angie Kreitzer, the Ohio Women’s Bowling Association Hall of Famer, who died at 34 in 2003, is there. So is famed Chaminade football coach Fuzzy Faust.

Al Bart, one of Fordham’s famed “Seven Blocks of Granite” is in Section 29, as well. Back in the 1930s Fordham was a football powerhouse and its fabled offensive lines featured the likes of All American Alex Wojciechowicz, Bart and Vince Lombardi.

Bart went on to win an NFL title with the Chicago Bears in 1943 and later ended up in a Kettering nursing home where he died in 2003 at age 87.

Eddie Brinck, a national motorcycle champ in the mid-1920s from Dayton, is at Calvary, too. He was regularly in the headlines and one old newspaper account I found from back then described him as “a man so dapper that he more consistently looks like a Hollywood playboy.”

Travelling at a high rate of speed during an Eastern Stakes Exposition race in Massachusetts in 1927, his motorcycle blew a front tire and crashed and he was killed. His death made front-page headlines here for days.

Meade mentioned two other sports figures Friday:

Ward Freeze, once a Calvary trustee, had been a pro wrestler who appeared in the ring as Lord Ward

“This was from the big-time wrestling days,” Meade said. “He wore a gentleman’s cape, a top hat and carried a cane. He competed against guys like Bobo Brazil and Pampero (Firpo.) He had some stories”.

And with a chuckle he also recalled Mac Richards, a senior citizen powerlifter who became a 12-time national champ. I wrote about Richards when he died at age 80 in 2003. Although ailing, just a couple of weeks before his death, he had walked into powerlifter Larry Pacifico’s Champions Gym and did 25 pull-ups.

At 77 he still could bench press 350 pounds, squat 470 pounds and dead-lift 490 pounds.

“I met him once and that has personally impacted me to this day,” Meade said. “He had come to make arrangements for his wife and when we shook hands, his grasp was so firm I knew he could crush me and make me cry like a little baby in a second.

“It wasn’t just the squeezing, it was the texture of his hand. It was like a rock.

“And that’s why his grave is so fitting now. The marker is a gigantic piece of granite.

“That’s just perfect.”

About the Author