Not with the gala scheduled to happen next Saturday in Brooklyn.

“Growing up with Roger, he took me everywhere with him in order to meet girls,” she said with a laugh a couple of days ago. “I was younger than him and the girls all would say, ‘Oooh, look at your little sister! She’s so cute!’

“I helped him get noticed. That got him in with the women.”

Campbell, who’s now 79, enjoyed remembering those days growing up on Prospect Place in Brooklyn:

“I followed Roger like a little puppy. I loved my brother. I loved when he was around.

‘When he’d come home from Dayton to visit, I’d call my mother from school and say, ‘Tell Roger I’m not feeling well.’ It was just so he’d come pick me up.

“Roger was a blessing to all of us. The times he came from Dayton, he made sure to sit and play poker with our grandfather.

“Those were good times.”

That was before they were not.

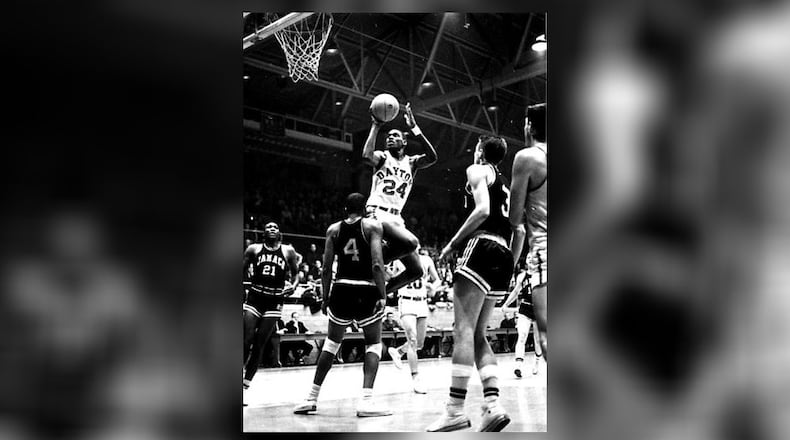

Brown is arguably the greatest basketball talent ever to wear a University of Dayton basketball jersey. He certainly was the most shabbily treated.

Not just by UD, but by the NCAA, the NBA, and even the folks who chose the U.S. Olympic team.

Brown, the star of the 1960-61 Dayton Flyers freshman team in a time when first-year players were not allowed to play varsity, was unfairly smeared in a probe of gambling and game fixing that rocked college basketball back then. Fellow Brooklynite Connie Hawkins, a star at Iowa, got the same treatment.

Neither Brown nor Hawkins was ever charged with any wrongdoing and neither had associated with the two gambling figures — former NBA player Jack Molinas and bookmaker Joe Hacken — who had seduced them (as they had many other players) during the previous summer with meals, movie tickets and small favors in exchange for introductions to other playground standouts.

None of Brown’s introductions involved players who were charged with anything either.

Regardless, when he was questioned by the Manhattan district attorney, UD officials did not stand by him. Instead, they revoked his scholarship and kicked him out of school, moves that all but crushed him and his family.

He stayed in Dayton for six years after his dismissal, initially clinging to the false hope that the school would have a change of heart.

A hero in West Dayton from the time he arrived in town, Brown spent the early years of his exile living with Azariah and Arlena Smith in their small home on Shoop Avenue.

He worked the night shift at Inland and played basketball on local industrial league, AAU teams — first Inland and then Jones Brothers Mortuary, where he teamed up with other local standouts like Ike Thorton and Bing Davis.

Though blackballed by the NBA — a stance that would cost the league $2 million in damages years later —Brown eventually was thrown a lifeline by the upstart American Basketball Association.

The brand-new Indiana Pacers made him their go-to scorer and, in his eight years with the team, he led it to eight straight playoffs, won the ABA title three times, was a four-time All Star and years was named to the All-Time, All-ABA team.

In 2013 he was inducted in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

Since then, UD — thanks to the efforts of President Eric Spina, who early on was inspired by Bing Davis — has made great strides in rectifying its past sins and honoring Brown meaningfully so current students can learn some heartfelt lessons from his saga.

But even so, it’s hard to forget the toll this ordeal took on Brown.

When Brown’s and Hawkin’s names got unfairly tried to the point-shaving scandal — which eventually was said to involve 28 athletes from17 schools in 39 different games — they were scooped up by the Manhattan DA and kept incommunicado in a hotel room for four days where they were grilled without an attorney present and were not permitted an outgoing phone call to their families.

Even when Brown was released, the authorities didn’t relent.

“It was like we were caught in a maze,” Judy said. “The DA had cops sitting in front of our door. like they expected Roger to…I don’t know what. They followed him when he was going down the street to the store or the rec center.

“There was a lot of pressure on all of us. It worried my mother, and my grandfather would say, ‘I’m going out there and knock their heads off!’

“And we’d say, ‘You can’t do that, you’ll be locked up.’

“Our grandparents helped raise us and we were close. My grandmother kept saying, ‘Is Roger going to jail? Is he going to jail?’”

Back in Dayton the Smiths received threats for allowing Brown to live with them and Arlena said Roger would have nightmares and cry out: “Leave me alone. I didn’t do anything.”

Judy said her mother sensed trouble:

“Roger was so depressed that at one point my mother said, “I have to go out there with my son.’ He sounded suicidal to her.’

“It was just a very tough time.”

And that’s why next Saturday — June 22 — is so meaningful.

Brooklyn is renaming part of Prospect Place, the street where Judy still lives in the home that’s been in her family 74 years. It now will be called “Basketball Hall of Fame Roger Brown Way.”

Judy said the sign will be placed at the corner of Prospect Place and Utica Avenue. It’s that same corner cops shadowed Roger in 1961 for something he did not do.

The street naming is just part of the all-day festivities said James McDougal, who organized the event along with Linda Squires and others.

There will be a pop-up museum filled with remembrance of Brown, including artwork and an old Jones Brothers Morticians photo sent by Bing Davis; and a treasured Dayton Skyscrapers art exhibit rendition of Brown by artist James Pate that Spina and his wife Karen bought so it could be displayed on the UD campus.

There will be a health fair that includes cancer screening — Brown died of liver cancer in 1997 — social justice discussions, music and food.

Several former pro players are coming in and Ray Haskins, the legendary New York City high school and college coach, educator and head of the Public School Athletic League (PSAL), said they all will gather the night before for dinner and stories at the well-known Junior’s Restaurant on Flatbush Avenue.

Davis said he had heard the Indiana Pacers may be represented there by Obi Toppin, who’s also from Brooklyn and UD and now is a stalwart of Roger’s old pro team.

But the most important thing that could happen, said McDougal, would be current Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg accepting their offer to come to the affair and exonerate Brown and Hawkins.

“That’s the big thing,” said McDougal, who is a community activist. “The DA here has been quite busy lately, but we hope he gives the family a measure of justice by announcing the innocence of Connie Hawkins and Roger Brown in those scandals in the early 1960s.

“We’ve pushed them on that, and they’ve done a little homework on their own and agree with us.

“Even though Roger persevered, he went through a lot. We want people to know it never should have happened.”

Judy praised the efforts of McDougal, Squires and the others and relishes the prospect of redemption:

“Roger needs to have his just due.

“A lie can’t last forever.”

One of the best of Brooklyn

Roger Brown is one of the best basketball players ever to come out of Brooklyn, which has been a hoops haven for more than 60 years. Eight players from the borough have been enshrined in the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

“Roger was a special player” said Haskins. “He and Connie basically put the seal on it when they talk about the best players coming out of New York City.

Proof of that lit up the marquee at the old Madison Square Garden on March 15, 1960, when a crowd of 18,000 showed up to watch Brown’s Wingate High team meet Hawkin’s Boys High in a semifinal of the PSAL Tournament.

Haskins said his friend Dennis Watson, who was a back-up center on the Boys High team, once told him this story:

“Coach Howie Jones of Boys High was preparing his team to defend Roger and he looked at Connie and said, ‘Do you think you could hold Roger?’

“And Connie said, ‘Coach, I’ll try.’

“That took everyone aback because they’d never heard Connie say anything like that before. He could hold anybody.”

But on that day, he could not stop Roger, who scored 39 points.

Hawkins fouled out in the third quarter with 18 points and 13 rebounds. Years later he said if there had been a three-point line Brown would easily have had 50.

When he got to UD, it was more of the same. He teamed with fellow freshmen Bill Chmielewski, Gordie Hatton, Chuck Izor and Jimmy Powers to form one of the most talent-laden groups the Flyers ever put on the floor.

The team drew big crowds to their games and went on to finish as national AAU runners up. The next year, without Brown, they won the prestigious NIT.

Brown’s troubles came to light when he had to return to New York for traffic court after being involved in an accident in the summer as he drove Molinas’ car.

Although Brown had no contact with Molinas or Hacken while he was at UD and never was found to have been involved in any suspect deeds on the court, the Manhattan DA had found a scapegoat to squeeze.

It’s thought UD overreacted, in part, to minimize an upcoming sanction by the NCAA when it was found the school had paid for Brown’s return trips to New York for court.

After he was dismissed at UD, Brown asked the Smiths — who he had met when the Flyers freshmen played the Inland team that Azariah coached and for whom Arlena kept score — if he could live with them.

She became a guiding light for Brown, making sure he helped do the wash on Mondays, ate his okra and went to church on Sunday. She also taught him to dance.

On Wednesday nights, Brown would go to Cincinnati to work out with the Royals’ Oscar Robertson. He hoped the team would pick him up, but it refused.

When the ABA tipped off in 1967, the Pacers tried to draft Robertson, who’d be a hometown hero in Indianapolis, but he declined and suggested Brown instead.

At first, Roger didn’t know if he wanted to give up his seniority at Inland. He wasn’t sure the ABA or the Pacers would last.

They did, thanks in a big way, to him.

That was never more so the case than in the 1970 Championship Series against the Los Angeles Stars when he scored 137 points in the final three games. That included 53 points and six assists in Game 4 and 45 points in the title-clinching Game 6.

Teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Mel Daniels once told me Roger was the best clutch player he’d ever seen:

“Our final play of the game should have been called ‘Give the ball to Roger and let’s go drink some beer!’”

‘I loved UD’

Just weeks before he died, I talked to Brown — who had been a four-term Indianapolis city councilman and was deeply involved in charity work — by phone from his Indiana home.

He could barely speak above a whisper, but his tone became animated — and the affection noticeable — when he talked about Azariah and Arlena, and about UD.

“I loved UD,” he said. “I still love UD.”

That sentiment and Bing Davis’ stories on his friend and the unfair shake he got here decades ago, struck a chord with Spina two years after he took over the presidency at UD.

After buying the Pate piece and doing some research of his own, Spina became instrumental in launching the Roger Brown Residency in Social Justice, Writing and Sport at UD in 2019.

When Malissa, one of Brown’s daughters came over with her family for the festivities, Roger’s three grandsons immediately bonded with Davis and they called him their unofficial grandfather.

She told an Indianapolis writer how important it was that her boys could learn more about who their grandfather really was.

And that’s what next Saturday is about, too.

“I’m just happy that the Roger Brown Committee was able to get this done,” Judy said. “It’s really a blessing. I’ve been fighting for it for so long. I wanted to honor my brother in the correct way.”

A lie can’t last forever.

But a street sign can help keep a name alive for all to see.

About the Author