“Dayton Inspires.”

Every day you see all walks of life — whether it may be mid-morning delivery truck drivers or nighttime revelers from the surrounding restaurants and bars, neighborhood dog walkers or Stivers High students walking home from class — posing in the frame as someone else takes their photo or they simply take their own.

Gilbert King, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author and cohost of the tremendously popular, multi-narrative podcast “Bone Valley” — which centers on the prosecution and 35-year imprisonment of Leo Scofield for the murder of his 18-year-old wife, Michelle, in Florida, and evidence that indicates he was wrongly convicted — said he’s never ventured into the Oregon District frame, but he insisted he certainly has been inspired by Dayton.

It’s one of the reasons the Brooklyn-based writer — who along with Amanda Knox, the American college student who was imprisoned four years in Italy for a murder she did not commit and whose story became a popular Netflix documentary in 2016 — will headline “An Evening for Justice” at the Victoria Theater on Feb. 29 that will benefit the Ohio Innocence Project.

King’s connection with Dayton began some 11 years ago when his New York Times bestseller “Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys and the Dawn of a New America” was the 2013 nonfiction runner-up for the Dayton Literary Peace Prize.

It’s the story of four young Black men falsely accused of raping a white farm girl in Groveland, Florida in 1949.

A sheriff’s posse of some 1,000 white men chased and killed one of the purported suspects, shooting him over 400 times.

After coerced confessions, the other three were convicted. Two years later, two of the cases reached the Supreme Court on appeal and Thurgood Marshall, backed by the NAACP Defense Fund, acted as their counsel.

The court overturned the convictions, but as the two men — handcuffed together — were being returned from the state penitentiary to the county jail, they were shot by Lake Country Sheriff Willis McCall, who King has described in the past as making the notorious Bull Connor, the brutal, white supremacist lawman from Birmingham, Alabama, “look like Barney Fife.”

One of the prisoners died on the side of the road. The other survived. When an NAACP representative petitioned the Florida governor to suspend McCall, his house was bombed and he and his wife were killed.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that the other two falsely convicted men were released from jail. In 2019 — six years after King’s stirring, Pulitzer-winning effort was published — the Groveland Four finally were pardoned.

Although his book finished as a runner-up here, King doesn’t think of Dayton as the town where he was slighted. Instead, he said it’s a place where he has found full embrace.

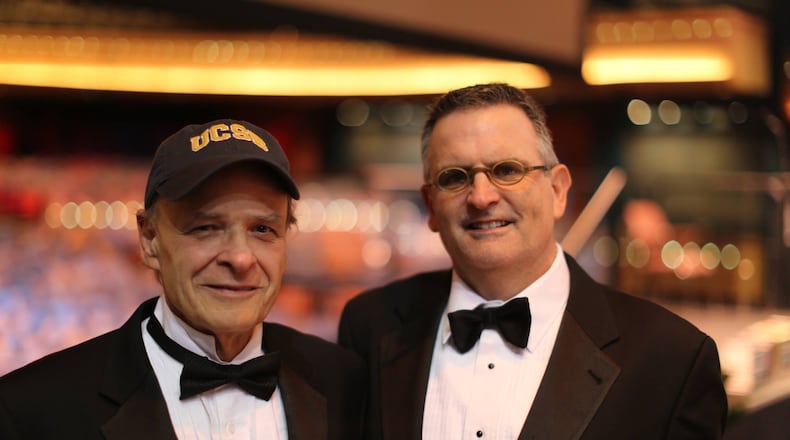

Over the years he’s made many friendships here, from Dayton Literary Peace Prize founder Sharon Rab and her late husband Larry, a local attorney, to Steve Dankof, the Montgomery County Common Pleas judge who started “An Evening for Justice” in Dayton eight years ago.

Inspired by the people he’s met through the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, King said he’s attended the festivities surrounding the annual awards for 11 years now. He was the master of ceremonies at the event last November.

Two years ago, at Dankof’s request, he returned to Dayton and wowed a crowd of common plea judges. In recent years he has spoken at local colleges, including Sinclair and Wright State.

Along the way he’s also become a fan of Dayton Flyers basketball and UD Arena.

“Some of the Peace Prize people have taken me to Flyers games,” he said. “I’m a huge fan of that arena. I’ve been to a lot of college basketball games and it’s the most intimate court I’ve ever been to for a game. It’s great.”

He said he’s also a huge fan of the Wright brothers and Paul Laurence Dunbar, enjoys the Air Force Museum, and, as an avid golfer, has played some of the best golf courses here.

“Yeah, he loves Dayton and will come back at the drop of a hat,” laughed Dankof.

His real affection for Dayton though, King said, is because of what happened to him as a chronicler of the human condition once he came here.

“I came to writing a little on the late side compared to some people,” the 61-year-old King said. “And I was influenced by going to the Dayton Literary Peace Prize year after year and seeing people like Bryan Stevenson and Isabel Wilkerson.”

Stevenson is the New York University law school professor who founded the Montgomery, Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative, and Wilkerson is the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and celebrated author known for her books “The Warmth of the Sun” and “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents.”

“I was around all these great writers, and I saw the work they were doing, and it just really inspired me to make sure I was making my time here on earth more valuable,” he said.

He’s done that with the three books he’s written and now with the Bone Valley podcast he cohosts with producer Kelsey Decker.

The podcast — in which he and Decker discovered new evidence and have a different man admitting on tape (and since on the witness stand) that he murdered Michelle — already has had over 10 million downloads.

“I can’t imagine that,” he said quietly. “That’s like Harry Potter numbers!”

He’ll talk about the Scofield case at the Victoria Theater. And while he and Decker are adding bonus episodes to their nine-part podcast — especially since it appears Scofield may finally be paroled this spring — King also has begun work on a book on the case, the offshoots that have come from it and some of the personal involvement they had with the investigation.

As he talked about that by phone the other day from New York, he reflected on his Dayton connection again:

“I think just the influence the Dayton Literary Peace Prize has had on me, and my writing has really put me in a perfect place to continue to do the stories I care about. It definitely shaped me, and I’m really grateful for that.

“I wanted to make a difference and social justice was one area where I felt I could do that.”

Finding stories of injustice

After graduating from high school in Schenectady, New York in 1980, King came to the University of South Florida in hopes of becoming a standout second baseman on the Bulls baseball team.

While some talented Latin ballplayers on the roster helped derail his future baseball plans, he eventually would find far more fertile ground in Florida than what he had traversed on USF’s Red McEwan Field.

After some freelance and ghostwriting jobs back in New York and a stint a fashion photographer, he found his calling with his first book, “The Execution of Willie Francis: Race, Murder and the Search for Justice in the American South.”

It was the story of a 16-year-old African-American boy who was arrested for the murder of a white pharmacist in St. Martinville, Louisiana. His original lawyer offered no defense, and an all-white jury convicted him after just 15 minutes of deliberation. But his 1946 execution failed when the jolts of the mis-wired electric chair weren’t enough to kill him.

Although a new lawyer argued before the U.S, Supreme Court that it would be “cruel and unusual punishment” to strap Francis into the chair again, Judge Felix Frankfurter, in a decision he would later rue, voted against his conscience and provided the final yes vote in a 5-4 decision to allow the second execution attempt, which was successful in 1947.

King followed that with the book on the Groveland Four and then returned to Lake County, Florida, and the cruel reign of McCall for the book “Beneath a Ruthless Sun: A True Story of Violence, Race and Justice Lost and Found.”

It recounted the story of Jesse Daniels, a white, mentally-disabled youth who was framed for a rape he did not commit, and it detailed the intimidation and threats faced by a nearby, small-town journalist Mabel Norris Reece, who for years reported on the bigotry and hatred of McCall and the Ku Klux Klan.

Both threatened her with everything from cross burnings in her yard and bomb threats to poisoning the family dog.

“These stories might have been forgotten unless somebody looked into them,” King said. “And I just have a strong distaste for bullies who use their power to keep people down. That just speaks to me.

“So, when I find these stories of injustice, I feel people need to be aware of them. I think it’s important that people are reminded that it wasn’t too long ago when this country could be extraordinarily unjust to some people.”

Continuing the work

“As a narrator I try to do things that keep people turning the page,” King said. “People might see it as a crime narrative, but by the time they get done, they’ve learned other things about civil rights, history and race.”

Dankof agreed:

“Each story like this is a ‘whodunit.’ Whether it was Dean Gillispie right here in Fairborn (he was wrongly convicted and imprisoned for over 20 years ) or the Groveland Boys or Leo Scofield or Amanda Knox, people didn’t know who the real attacker was.”

And that, he said, can sometimes lead to wrongful convictions for a variety of reasons:

“Human memory and its frailties, eyewitness identification and its frailties, cross-racial identification and its frailties.”

In the case of Gillispie, Scott Moore, the Miami Township police officer investigating three area rapes, manipulated the photo lineup to get three women to point at Gillispie as their attacker and suppressed evidence that would have cleared the then-24-year-old Fairborn man.

Gillispie was imprisoned from 1991 to 2011.

Thanks to the work of the Ohio Innocence Project, state, federal and the Ohio Supreme courts issued rulings that released him, exonerated him, and admitted he was wrongly imprisoned. Fifteen months ago, he won an Ohio-record $45 million settlement .

Over the past 20 years, the work of Ohio Innocence Project has led to the release of 42 wrongfully convicted Ohioans.

In the Scofield case, the Florida Innocence Project has been working on his behalf.

The magnitude of those efforts can’t be overstated, Dankof said:

“There’s this notion in criminal law — it’s called the “Blackstone Ratio” — and its position is that it’s better that 10 guilty individuals go free than to have one innocent person suffer. That’s what it’s supposed to be, but the reality is sometimes the reverse of that.

“And while we don’t admit it in pleasant company and certainly don’t stand up and say it, the reality is we know we have convicted innocent people and continue to do so, and we have executed innocent people.”

He said that brings us to “one of mankind’s biggest fears — isolation. That’s what wrongful convictions are all about. That’s what’s at their core.

“Imagine sitting there rotting in a cell for something you didn’t do, screaming as loud as you can to be heard:

“’I didn’t do it!’

“’I didn’t do it!’

“At some point you lose all hope. That’s why these stories resonate with people. That’s why people are fascinated by them.

“That’s what Gil’s work is all about. And I think people will be spellbound by Amada Knox and her journey, her story of what she went through.”

Knox was wrongfully convicted in 2007 for the murder of a fellow exchange student she shared an apartment with in Perugia, was imprisoned four years and finally acquitted in 2015.

While the Evening for Justice presentations by Knox and King will enthrall and educate the audience, Dankof hopes the real beneficiary of the night is the Ohio Innocence Project, which is based at the University of Cincinnati and operates solely on donations.

Last month, the Neon Movies featured an evening of short films about Gillispie and the Innocence Project, followed by a question-and-answer session. It was sold out.

It was meant to hype the Feb. 29 main event at the Victoria and Dankof hopes another large crowd will show up. Tickets for the 7 p.m. event range from $28.50 to $43.50 and can be purchased at DaytonLive.org or by calling the ticket office at 937-228-3630.

Thanks to a generous donation by the Dayton Legal Heritage Foundation, over 100 area students will also get balcony seats for free.

Dankof believes people will be moved by the presentations:

“When they go home, I hope they not only realize the importance of the work being done by the Ohio Innocence Project, but that they dip into their pockets and financially help the group this year and continue to do so for years to come because what it does benefits all of us. They make us better as a people.

“Dayton is a generous community. It always has been, and I think it will be again.”

And if that is the case, the mural in the Oregon District is right:

“Dayton Inspires.”

An Evening for Justice

When: 7 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 29

Where: Victoria Theater

Featuring: Amanda Knox and Gilbert King

Tickets: $28.50 to $43.50 (purchase at DaytonLive.org or call ticket office at 937-228-3630)

About the Author