He feared he was going to weigh 300 pounds and be the laughingstock of the boxing world.

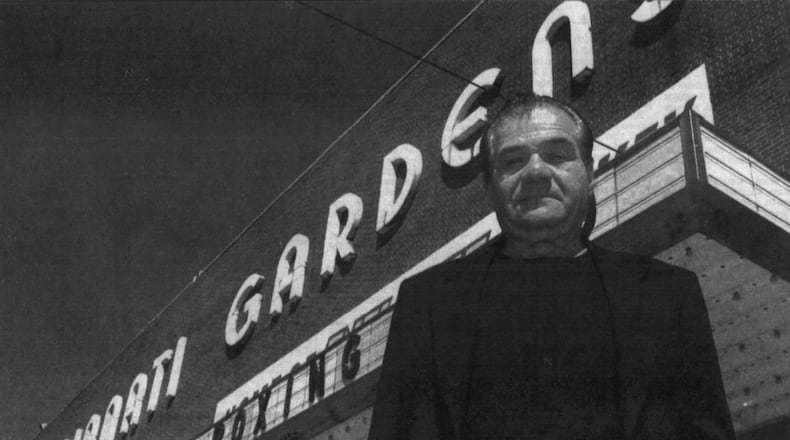

“Don’t worry about it,” assured matchmaker Don Elbaum, a Damon Runyan character with an elfin-face, slicked-back hair dyed jet black, a nose that looked like it had taken a punch or three and, when he laughed, eyes that melted to slits. “You’re gonna be OK.”

As Dokes stepped up, Elbaum said he was at his side, as was a ring card girl who’d been enlisted to sidle up to the guy handling the weigh-in.

The ploy worked and with the official sufficiently distracted, Elbaum was able to deftly move his thumb beneath the weight scale beam so that it registered just 282 pounds.

Dokes was delighted. Although he weighed 66 pounds more than he did when he’d become champ, he didn’t weigh three bills.

It’s stories like that that forever branded Elbaum a rapscallion of the ring, part P.T. Barnum, part, as well-known boxing author Thomas Hauser once put it, a travelling salesman who goes town to town selling magic elixirs. I especially liked the description longtime sportswriter Jerry Izenberg once used. He called Elbaum “a hustler without malice.”

Some people might not look favorably on Elbaum for his transgressions – and in the 1997 Erlanger fight, Dokes would suffer a broken jaw from a Phillips’ KO punch – but I appreciated him for who he was. There was a kindness in his con.

We first met almost 50 years ago at the Fifth Street Gym on Miami Beach, and he became one of the most colorful characters I knew in the sport I’ve been most drawn to throughout my career.

Elbaum died July 27th in Erie, Pa. His funeral was just over a week ago.

He was 94 and had been involved in boxing for over eight decades.

He promoted his first boxing show at age 15 and in 2019 he was enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Over the years he worked with many of the top names in boxing, including Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Robinson, Sonny Liston, Floyd Patterson, Roberto Duran, Vito Antuofermo and Aaron Pryor.

He also worked the other end of the sport when he put on his “World’s Worst Boxer” show in Warren, Ohio, in the early 1970s.

“Bob Spencer was the nicest kid, but his fight record was 0-13,” Elbaum once told me. ”He begged me to get him a win in his hometown, so I matched him with Johnny Howard, who was 0-18.

“I had some ‘so-called’ papers drawn up and they signed them. It said the loser would quit the fight game. A picture of that ran in the paper and we got a four-foot trophy. On the bottom, I had ‘World’s Worst Fighter.’

“It was nothing but a four-round fight at the Elks Club. We packed the place, and they paraded the trophy all around before the match.

“Then they fought, and you know what?.... It ended in a draw!”

How appropriate for the fighters and, of course, Elbaum.

He kept the gate receipts… and the trophy.

Although raised in Erie and based in Philadelphia in his heyday, Elbaum had a long connection to Ohio and especially Dayton.

He was born in Cincinnati and nearly blown up in Warrensville Heights, (that’s a story we’ll get to shortly.) But first his connections to the Miami Valley.

Besides Phillips, whom he matched several times in his career, Elbaum also put on a card featuring one of Dayton’s most storied fighters, heavyweight Tom “Ruff House” Fischer, who went 37-11, fighting some of the game’s biggest names in the 1970s and ‘80s, including Leon Spinks, Quick Tillis, Dokes in his prime, Jimmy Young and Ron Stander.

Elbaum made matches for Xenia heavyweight Jimmy Huffman, accomplished Dayton amateur Michal Blunt and Mike Wyant, a former Hamilton Garfield High wrestler who’d won a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star as a Marine in Vietnam.

Billed “The Hamilton Hurricane,” Wyant was 19-2 as a junior middleweight when he was shot to death outside of a bar at a Hamilton shopping center in 1979.

Elbaum promoted Aaron Pryor’s stoppage of Danny Myers at Hara Arena in 1980 and he put on numerous closed circuit shows here, including big fights like Ali-Frazier, Frazier-Foreman and Leonard-Duran.

Once at Dominics, I sat with him and asked about some of his most fabled boxing stunts:

- Like how he’d reached into the Detroit Red Wings’ trophy case at Olympia Stadium and awarded one of his fighters Gordie Howe’s MVP Trophy.

- How he had a Pennsylvania car dealer in a wig pretend he was the head of the state’s athletic commission and handle official duties at a Duran fight.

- How he sold advertisements on the soles of boxing boots worn by a soon-to-be-prone pug.

- As for his best escapade, he thought a few seconds, then laughed:

“How ‘bout the deal with Sugar Ray Robinson?

“I promoted three of his last four fights. The first was in Johnstown (Pa.) in October of 1965.

“Before the press conference, it hit me that it was exactly 25 years to the day since Ray had begun his pro career at Madison Square Garden.” Elbaum actually was off three days on the date, but in typical prizefight tradition, particulars sometimes go down for the count.

“With all the press gathered, I figured we needed something special,” he said. ”I had ‘em turn out the lights and in came the four best-looking girls I could find in Johnstown. They carried a big cake decorated with 25 candles.

“Then I walked over with my hands behind my back and said, ‘Ray, now don’t ask me how I did it... but here.’

“I pulled out a pair of old boxing gloves and said, ‘These are the gloves you wore in your first fight!’

“I could see Ray was moved. There were tears in his eyes and he cradled those gloves like a baby. The cameras were flashing. People cheered and that’s when some guy yelled, ‘Ray, put ‘em on.’

“I looked at those gloves and horror hit me.

“And when the guy yelled again, I leaned over to Ray and whispered, ‘Don’t you do it. You hear me? Don’t put them on.’ “He was puzzled until he looked closer at the gloves – which really had come from the trunk of my car – and saw they were both right-handed. “Without missing a beat, he looked up as though still moved, and told the guy, ‘I can’t. I just can’t bring myself to put them on right now.’

“The guy got emotional and nodded and said, ‘I understand, Ray.’”

Don King connection

Asked if he had any regrets, Elbaum laughed and said there was one.

He had introduced Don King, the Cleveland numbers kingpin who was fresh out of prison, to the fight game.

For his debut, King said he wanted to put on a charity show to help a financially troubled hospital in Cleveland that cared for poor people.

He knew of Elbaum’s connections and asked if he could get Ali.

Elbaum did.

Ali fought the exhibition and Elbaum said $85,000 was raised.

But in the end – in what became the blueprint of King’s career – the hospital only got $1,500.

“Don once told me I’d have been a billionaire if I’d stuck with him,” Elbaum said.

“I told him, ‘No, I would have ended up in jail!’”

A beautiful sickness

Actually, Elbaum did do a brief stint behind bars for tax evasion in the early 1990s, but soon after that he was right back to the game he’d first been drawn to as a youngster when his uncle took him to see featherweight champ Willie Pep outwit Paulie Jackson.

He claimed before that – at the prompting of his mom who’d been a concert pianist – he’d been something of a child prodigy on the piano.

But after being introduced to boxing, the music that moved him most was the sound of a boxing gym: chattering speedbags, whirring jump ropes and a ring bell keeping time on sparring sessions.

Over the years Elbaum wasn’t just a promoter and matchmaker, he sometimes worked a boxer’s corner, jumped in as a referee and once donned a white coat and gave prefight exams when the real doctor didn’t show.

Four times, he even got in the ring when an opponent bailed out at the last minute.

“As the ref had us touch gloves, I’d whisper to the other guy, ‘Don’t forget who’s paying you tonight,’” he said.

Elbaum once told Hauser:

“Boxing is in my blood. It’s a beautiful sickness.”

And on a winter night in 1972 that sickness almost became fatal when someone planted four sticks of dynamite in the front wheel well of his 1967 Pontiac that was parked at the Highlander Motor Inn in Warrensville Heights.

As police quizzed him afterward, they asked if anybody had a beef with him.

With perfect timing, Elbaum deadpanned:

“You’re gonna need a bigger notebook.”

In truth, most people liked his roguish mix of chutzpah and charm.

Once I asked how old he was – I later found out he was 63 then – but he fended me off with that day with a smile and a verbal jab:

“I won’t tell you.

“Besides, my girlfriend back in New York thinks I’m 46.”

With that, he leaned over and whispered:

“And my other girlfriend thinks I’m even younger than that.”

About the Author