A little further along in the cemetery, another hillside was covered by a magical blue carpet of Glory-in-the-Snow.

The view seemed perfect, that is until you looked down at the flat, weathered gravestones from a century past that bore engravings like:

Baby Marie Swank, July 25,1918

Our Darling Eugene M. Lambert 1917-18

Baby Lawson Groomes Jr. 1917-18

Dustin Murray, died Mar. 27, 1918 – 3 mos. old

James Tharp, Feb. 1918 – Mar. 1918.

Grave after grave in Section 111 of the cemetery was a reminder of the heartbreaking deaths that hit Dayton in 1918. Section 117 was filled with more graves from that year, especially those of people who died way too young.

This was the toll of the deadly Spanish flu of 1918 – 657 people in Dayton perished that year and 44 more died in January of 1919 — a pandemic precursor of the coronavirus Covid-19 that is laying siege to the world today.

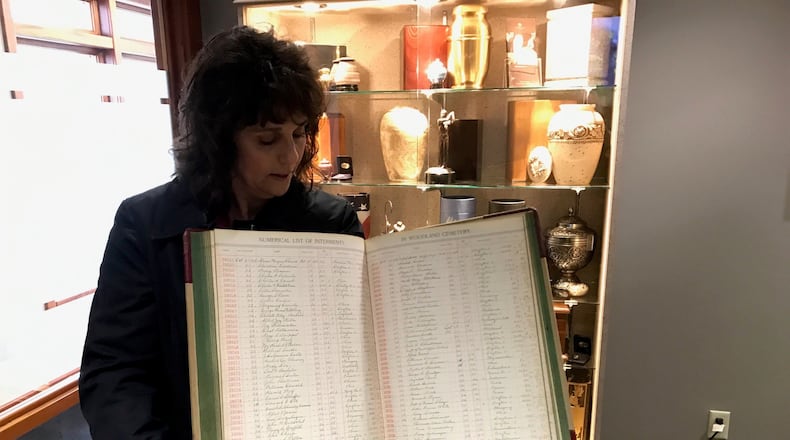

To further comprehend the extent of loss in 1918, you needed only follow Angie Hoschouer, Woodland’s manager of development and marketing, to a back room in the cemetery offices where she pulled a bulky ledger from a top shelf.

It was one of the Interment books in which each Woodland burial is listed by date and includes the person’s age, birthplace and death date.

She opened the book to the last few days of October 1918, a month in which 195,000 people in the United States died from the Spanish flu.

“Here’s the 28th,” she said as she ran her finger down the column of names and counted: “Nine… 10…11 people were buried here that day.” She tallied 13 burials on the 29th and another 11 on the 30th.

“It’s just day after day after day,” she said quietly.

The numbers were high, but the ages were low. Of the 13 October 28 burials, 10 people were under 35. The next day it was eight of 11.

Unlike with Covid-19, where the elderly are the most vulnerable, the Spanish flu – which came in waves over 1918 and 1919 and claimed 675,000 lives in the United States and an estimated 50 million people worldwide – targeted younger adults and children.

With that in mind, it’s no surprise that the sports world was hit hard by the deadly outbreak. And while ball games and the like are not of prime concern during a global pandemic, the competitions do offer a diversion and often the illusion of business as usual.

But that was impossible in 1918.

Athletes died. Seasons were upended.

The football team at the University of Dayton – then known as St. Mary’s College – was able to play only two games in 1918. Sixteen of the 88 colleges playing major college football then didn’t play a single game that year.

The Dayton Triangles did salvage a team and went 8-0 to win their first Ohio League title, but that was due, in part, to some other clubs not playing because they’d lost so many players to illness or deployment in World War I.

Professional baseball – which banned the spitball for health reasons and even had two minor league teams play a game while wearing surgical masks – couldn’t keep the flu at bay.

Several players, at least two umpires and a pair of noted sportswriters, perished in the 1918 pandemic. So did college football players, boxers and even a hockey player involved in the 1919 Stanley Cup championship between the Montreal Canadiens and Seattle Metropolitans.

The Canadiens had knotted the series 2-2-1 with an overtime win, after which several of their players collapsed with temperatures near 105 degrees. Several were rushed to the hospital.

Montreal General Manager George Kennedy also fell ill and soon the team didn’t have enough players to take the ice. Kennedy said the team would forfeit, but Seattle refused to capitalize on an ailing rival and would not accept the title.

Four days later Canadiens’ defenseman Joe Hall died from the flu. And Kennedy never fully recovered and died in 1921.

While it’s become tradition that the winning team and its players are engraved on the side of the Stanley Cup, the 1919 series got this inscription:

1919

Montreal Canadiens

Seattle Metropolitans

Series Not Completed.

City shuts down

On Sept. 28, 1918, Dr. A. O. Peters, Dayton’s health officer, warned residents in this city of 150,000 about a coming influenza epidemic that already was hitting the East Coast.

People soon were cautioned to isolate themselves and avoid public gatherings. By Oct. 8, there were 168 flu cases in the city and an estimated 2,600 students were absent from classrooms. Schools, theaters and churches were closed and a day later, saloons, soda fountains and pool rooms were closed.

But like you’re seeing now, some people skirted or ignored the rules.

Bars here were allowed to partially reopen.

The Columbus Chamber of Commerce allowed a previously-scheduled concert at Memorial Hall to go on, arguing “only a higher class of people” would attend.

Philadelphia still held its Liberty Loan war bonds parade on Sept. 28. It drew 200,000 people and that only accelerated the infection rate, so much so that on Oct. 16 alone, 759 people in the city died from the flu.

According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, there were 12,191 flu deaths there in four weeks.

Back then people hoarded supplies like they are now. Stores couldn’t keep Vicks VapoRub – thought to aid the afflicted since there was no vaccine – on the shelves.

There was a severe shortage of nurses and that prompted a general call by health officials for women 18 to 30 with one year of high school education to volunteer.

After a couple of weeks of communal containment, officials – wrongly thinking the peak of the epidemic had passed – eased up on restrictions and soon the infections surged upward again.

Hoschouer made that point by turning to December in the ledger: “Here are nine burials on Dec 7…. Everyday there’s 5 to 10.”

One place in Ohio that was especially decimated was the Camp Sherman, the World War I military training base outside Chillicothe where 5,686 personnel fell ill with the flu and 1,777 died.

There were so many deaths that the Majestic Theater in town was used as morgue and the blood and bodily fluids that washed out into the alley changed the passageway’s name to Blood Alley.

Funerals required closed coffins. As Christmas approached, no store Santas were permitted.

And while the sports seasons changed, the effects of the Spanish flu – which did not originate in Spain but likely, some experts say, at Camp Riley in Kansas – continued to impact competitions.

St. Mary’s – which would become the Dayton Flyers in 1923 — played just six basketball games in the 1917-18 season and seven the next season, about half of what was typical then.

So this past season wasn’t the first time a season here was cut short by a pandemic.

Baseball, boxing hard hit

This year Major League Baseball has pushed the start of the season back to at least mid-May. The season was shortened in 1918, too, but that didn’t keep everyone safe.

Several minor league players died, as did former Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians and Boston Braves outfielder Larry Chappell, 22-year-old Negro Leagues star Ted Kimbro, who had enlisted in the Army, respected umpire Silk O’Loughlin and Boston Globe baseball writer Eddie Martin, who had been the official scorer for the 1918 World Series.

The Baltimore Sun reported that Babe Ruth, then a strapping 23-year-old pitcher with the Boston Red Sox, was stricken with the flu, but he overcame the illness and won two World Series games

In boxing, former heavyweight champs Jim Jeffries and Tommy Burns both recovered from the flu.

Jack Dempsey’s bout with Battling Levinsky – set for Philadelphia in late September – was pushed back to November and Dempsey won with a 3rd round knockout.

Several boxers weren’t so lucky though. Lightweight contender Matty Baldwin, who had gotten through 101 pro fights, couldn’t beat the flu. He was 33 when he died. At least a dozen other boxers perished, as well.

One was Battling Jim Johnson, who five years earlier had fought heavyweight champ Jack Johnson to a draw in Paris. It was the first time two black boxers ever fought for the heavyweight crown.

Battling Jim was scheduled to fight Sam Langford in Lowell, Massachusetts, but the bout was postponed to keep everyone safe.

But while he waited for the fight to take place he contracted the flu.

On Nov. 1, Battling Jim Johnson died at age 31.

Back in Dayton that day, seven people were buried at Woodland Cemetery.

Among them was Esther McFarland, who was just 21, Mike Moshos, who was 30, and James Dale Sauter.

He was just one.

About the Author