The slang expression – sometimes delivered with swag and sexy undertone and often used as the title for songs, a TV series, a film, a video game and more – has one specific answer when it comes to Ohio Stadium.

And it has its roots right here in Dayton.

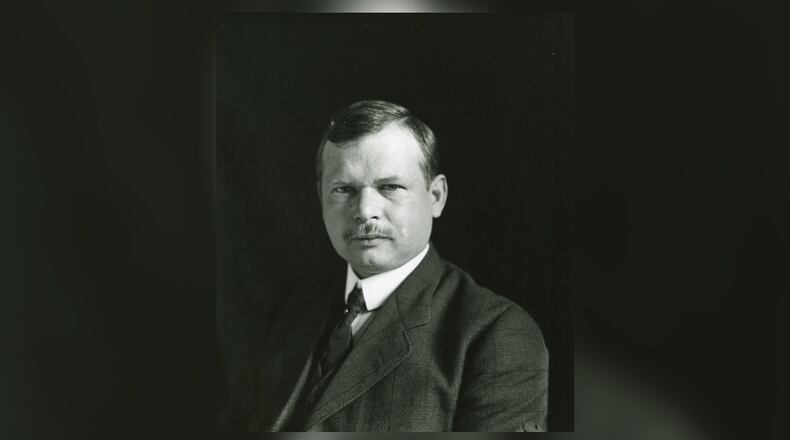

Thomas Ewing French – he’s your daddy.

According to local historian and Wright Brothers author Louis Chmiel, French – a product of Central High, Dayton’s first high school, where he was part of the Class of 1890 that included Paul Laurence Dunbar and Orville Wright – later was given the affectionate moniker: “The Daddy of Ohio Stadium.”

He’s the visionary most responsible for the building of the iconic Horseshoe-shaped stadium that is celebrating its 100th anniversary this season.

It’s one of the best-known sporting venues in America and the most familiar image of Ohio State University.

And thanks, in part, to French, OSU has long been a major player in college athletics and especially football.

An OSU engineering professor who would go on to write a popular text book – “A Manuel of Engineering Drawing for Students and Draftsmen” that was used for generations in more than 500 colleges around the world – French was the school’s de facto athletics director in the late 1890s and the turn of the century.

He organized teams for various sports, lined up coaches and scheduled competitions with area colleges.

In 1912 – realizing Ohio State needed to play bigger-name football opponents if it one day wanted to rival the game’s gridiron heavyweights back then: Harvard, Yale and Princeton – he pushed the school to join the Western Conference, which eventually would be known as the Big Ten.

And he’s the man who refused to wilt when critics – and there were many – roundly dismissed his dreams of a big-time football stadium that would replace Ohio Field, which initially held 5,000 seats and later, at his prompting, had expanded to 10,000.

According to the 2003 PBS documentary, “The Birth of Ohio Stadium,” one vocal critic – Board of Trustees member and acclaimed physics professor Thomas Mendenhall – viewed French as a megalomaniac.

He said 45,000 seats were far too many for a newly proposed stadium and worried about the “psychological effect” there’d be on the OSU football team that would be playing in front of a stadium of mostly empty seats.

Credit: Phil Ellsworth / ESPN Images

Credit: Phil Ellsworth / ESPN Images

Today, though, Ohio State football has one of the hottest tickets in the college game. Last season, the Buckeyes averaged nearly 97,000 fans a game at home, fifth highest in the nation.

And yet, French – the man who planted the seeds of so much success and is remembered on the OSU campus with French Field House, the home to indoor track meets and several sports facilities – is all but unknown here in Dayton when it comes to his local upbringing and his link to Ohio State.

“This whole story has amazed me as I’ve developed it,” said Chmiel, who added a brief chapter on French in the 2017 second printing his book “Ohio: Home of the Wright Brothers. “There’s no one here in town that I could find who knew the man ever drew a breath.

“How he’s fallen off the radar here just amazes me.”

Strictly by chance, the 78-year old Chmiel – who got a chemistry degree at Miami University, launched the Iron Boar tavern on Patterson Road in the early 1970s and eventually was part of a group building replicas of the Wright Brothers experimental aircraft – discovered French’s connections to Dayton and later was led to his two grandnieces: Mary Sweet, an artist in Tijeras, New Mexico and her sister, Nancy Picard, who lives on their farm in Highland County, some 50 miles southeast of Dayton.

“This all came about by a very odd, serendipitous experience I had,” Chmiel said from his East Dayton home. “It was around 2016, a few years after I’d published my book. I was sitting here, reading under my reading lamp one morning and my TV was tuned into the PBS station, but with the mute on.

“At one point I happened to look up and I caught a glimpse of a photo on the TV screen. It was just for a couple of seconds, but I thought, ‘Wait, that looks like Orville Wright next to some guy I don’t know.’

“Then the camera focused on the other man. I had no idea who he was and because the sound was muted I didn’t know what was being said or what the show was about.

“Maybe a year later the show came on again. It was the documentary on the building of Ohio Stadium.” Although it never mentioned that French was raised in Dayton, Chmiel was intrigued by the Orville Wright connection and began to do research.

And what a story he found.

Roots in Dayton

Daniel French, Thomas’s father, was a minister and in 1879 he became the pastor of the United Presbyterian Church at Fourth and Jefferson streets in Dayton.

Thomas – who was born in Mansfield and then lived with his family at 51 Huffman Avenue in East Dayton – eventually ended up at the Fourth District School at the corner of Brown and Hess streets in the Oregon District.

The school house is long gone and it’s now the site of Newcom Park.

But back in the mid-1880s, it was the vibrant intermediate school where French became a classmate and friend of Paul Laurence Dunbar, who lived nearby on Howard Street and one day would become the acclaimed poet, novelist and playwright now revered as one of Dayton’s favorite sons.

Chmiel found an interview French did with the Ohio State Lantern in 1933 where he recalled his desk being directly behind Dunbar’s when they were in the eighth grade.

Come ninth grade, the pair was at Central High and met classmate Orville Wright who lived on Dayton’s West Side.

As was often the case back then, students quit school early.

Orville Wright did and, Chmiel discovered, French did too, leaving school midway through his junior year to study mechanical drawing at David Sinclair’s YMCA night school and get a job in the drafting department at Smith and Vail.

When French enrolled at Ohio State in 1991, his younger brother Edward – the grandfather of the aforementioned Mary and Nancy— was becoming a star tight end on the Central High football team. Wilbur Wright, a speedster running back, was his teammate.

Edward joined the fledgling Ohio State football club in 1895 and that’s about the time Thomas – who’d just graduated with a mechanical engineering degree and already was teaching at OSU – began to take a keen interest in sports at the college.

He thought they built character in students and that athletics was a great vehicle of recognition for the school itself.

The newly-formed OSU team played games at Recreation Park, located at S. High and Whittier streets, a considerable walking distance from the campus which then had an enrollment of some 1,400 students.

Back then the Buckeyes played against teams like Ohio Wesleyan, Wittenberg, Kenyon, Oberlin, the Dayton YMCA and Antioch College.

When students rallied to get a field closer to campus, French picked up the cause and Ohio Field was opened in 1898. It had 5,000 wood-plank seats and was open on one side, enabling fans to pull up in their horse and buggies and watch from their vehicles.

As crowds grew, French envisioned a far bigger stadium, one that would rival the Ivy League powers.

Harvard Stadium, the first concrete stadium of its kind, opened in 1903 and held 45,000 fans. Princeton’s Palmer Stadium held just over 45,000 and Yale would later build an oval shaped stadium that held 70,000.

While French was becoming an academic heavyweight at OSU – 11 years after graduating he was chair of the engineering department – he had heartbreak a home. His wife Ida died in 1903, leaving him to raise their young daughter.

His outlet became athletics and in 1909, with the school having just upgraded Ohio Field to 10,000 seats, he wrote an article for the Ohio State alumni magazine in which he made the bold prediction that someday the school would have a magnificent concrete stadium that would have a horseshoe shape and would rival stadiums in the East

While his views drew many naysayers, he had a like-minded backer in OSU president William Oxley Thompson, who eventually appointed him to head OSU’s athletic board.

French soon hired Lynn St John, another visionary, as the school’s athletics director.

The move to the Western Conference meant the Buckeyes were now playing Indiana and Illinois and Wisconsin.

And then came OSU’s ultimate dream weaver, Chic Harley, a speedy halfback from nearby East High, who, in his first year, led the Bucks to an undefeated 1916 season and victory in the conference championship over mighty Wisconsin in front of an overflow crowd.

Harley became the school’s first All American and French, as the documentary noted, went from “respected crackpot to a visionary with a good grasp of reality.”

Although he left to join the World War I effort as a U.S. Army Air Service pilot, Harley returned in 1919 and led the undefeated Buckeyes into the conference title game against Illinois that drew 17,000 fans to Ohio Field.

That was the springboard for French’s bigger-stadium push which he’d begun in earnest a year earlier when he hired 32-year-old architect Howard Dwight Smith, a fellow Daytonian who’d graduated from Steele High, to create designs for a new stadium.

Pleased with Smith’s work, French then hired him to run the project.

Eventually, the school agreed to a 45,000-seat stadium, but said it would have to be privately funded.

St. John and French had plans for an even bigger stadium, though they kept that idea under wraps as they began the fund-raising drive.

Parades were held through the city streets – one was with floats, bands and OSU students dressed in full athletic garb as they did calisthenics in the street; another had 1,000 military troops who then staged a mock battle on the banks of the Olentangy River – and drew crowds of 100,000.

Columbus businesses promoted the stadium idea and a committee visited each of Ohio’s 88 counties and enlisted support.

Within three months, $1.3 million had been raised.

Construction of the stadium – horseshoe-shaped to allow track events to be run out the open end – began in the summer of 1921 and French inconceivably vowed that the work would be complete in time for the 1922 season.

Some 40,000 cubic yards of concrete and 5,300 tons of steel would be used, but it was a time, as the documentary pointed out, when there were no forklifts, cranes or elaborate scaffolding setups.

And yet, that wasn’t the most mind-boggling part of the project.

The actual size of the “Horseshoe on the Olentangy” would surprise everyone.

Stadium opens

With its initially seating capacity of 66,210, Ohio Stadium was the largest poured concrete structure in the world. It cost $1.49 million and was ready for the Oct. 7, 1922 opener against Ohio Wesleyan.

A crowd of 25,000 showed up, meaning half the stadium was empty and that briefly gave French’s critics some ammunition.

But the official dedication was two weekends later – against rival Michigan – and it drew a massive crowd of anywhere from 72,000 to 78,000.

While attendance plummeted back down for the rest of the year, a glimpse of the future was revealed and French felt vindicated.

One person had become an OSU fan was Orville Wright, who French first took to a game in 1916 when Harley shined. And Chmiel found Wright had continued to attend games throughout the 1930s.

Speaking from her home New Mexico the other afternoon, 84-year-old Mary Sweet remembered hearing a story of her aunt riding from Dayton to an OSU game in the rumble seat of car. She said her sister, an OSU alum and Buckeye fan, once knew the story better, but has been dealing with medical issues recently.

Chmiel remembered hearing the rumble seat ride was in Orville Wright’s car.

Wright and French remained lifelong friends and Chmiel said Wright attended French’s funeral in Columbus in 1944.

It wasn’t long after that – in the years following World War II – that Ohio Stadium began to sell out. With future expansions, the packed houses continued.

As for French, Mary said the family always had called him by his middle name.

“He was Uncle Ewing to me,” she said.

“I was a little kid, but I remember him vaguely coming to visit and talking with my grandfather in the study. He did a nice etching once that we had on our wall for years

“I know my aunt, Virginia French Rose, was very interested in art and did some art work. But Uncle Ewing was very scornful of it. So she quit and never did it again.

“He could be very hard on people. He didn’t hold back on what he thought.”

And while that trait may have squelched Aunt Ginny’s art career, it certainly did paint a pretty picture of Ohio State football going into the future.

So in this centennial season at Ohio Stadium, you now can answer the question:

“Who’s Your Daddy?”

About the Author