Michael “Mickey” Carter, now 91, is a sports legend living quietly among us.

Coming of age in Louisville, Ky. during the Jim Crow segregation days, he went to Central High, which in those days, said Mickey’s sister Jacci, was “the only school black students could attend in the city.”

He became the quarterback sensation of the school’s barnstorming football team, orchestrating wins his senior season over teams like Nashville’s Pearl High, Lincoln High in East St. Louis, Chicago’s DuSable High, Dunbar High in Lexington and Dayton Dunbar, who he decimated with two touchdown passes, a 65-yard run and then another TD run in what ended up a 24-2 romp.

When he graduated in 1945, his class was the first not to have “Colored” included in its CHS title.

He accepted a scholarship to Wilberforce University and was there when it first split into two schools. He starred on the Wilberforce State team – known, at least to headline writers, as the Mighty Green Wave – a team that one day would become the Central State Marauders.

And, once again, his exploits were headline-making:

“Big Green Crushes Hawks 101-0,” read a Xenia Gazette story after Wilberforce routed the Wright Field Kittyhawks.

Mickey led the team to victory over Bethune-Cookman in Florida, wowed a crowd of 13,000 at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C. as he lifted Wilberforce past Tennessee State in The National Classic and then did the same against Prairie View in front of 15,000 fans on New Year’s Day in Houston.

That senior season in 1948 he was named a Black All American by the National Negro Press Association, the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier.

Also a boxer, he won he Dayton Golden Gloves and AAU crowns and even sparred two rounds with world welterweight champ Sugar Ray Robinson.

The Brooklyn Dodgers signed him in 1950 and he ended up playing the infield for two seasons with the Sheboygan Indians in Wisconsin. Drafted into the Army during the Korean War, he played baseball for service teams, as well.

His exploits as a three-sport star at CSU – and especially as the school’s first great quarterback – are what made him part of the very first class (1987) enshrined in the Central State Marauders Athletic Hall of Fame.

When Dixon – who later became a Dayton City Commissioner and then the mayor of Dayton – first went to Central State in 1959 as a freshman, he said Mickey already was “a legend on campus.”

“My freshman year he was my psychology teacher,” Dixon said. “And, you know, he didn’t talk a lot about his athletic days and what he did. He didn’t build who he was around his athletics and he well could have.

“Instead he made the focus education. He encouraged us to do our best in the classroom and encouraged us to make something of ourselves. He knew that’s the focus we needed if we wanted to be successful in the world. And after graduation he wanted us to represent the university – and ourselves – on the highest level.”

Dixon is still impressed how he didn’t make sports his currency.

Mickey’s sister, Jacci, who’s now retired in Scottsdale, Arizona, said she saw the same attitude when her brother, whom she calls Michael 0, a reference to his middle name, Owen – was in high school:

“He was a big star, but he never let it affect him. He just went about his business and never said anything about it.”

Craig Williams, a longtime Dayton educator and husband of Mickey’s daughter Denise, said nothing changed in later years: “I’ve known Mickey since ’88 and he’s just a modest guy. It’s only if you brought his sports career up that he would talk about it.”

And it wasn’t until Craig came across some of Mickey’s old scrapbooks – compiled by his late wife Barbara – that he realized the extent of his father-in-law’s athletic accomplishments:

“I started going through them and finally I said “Denise! Your dad was something else!’ She didn’t really know. She said, ‘That’s just my dad.’”

Denise knew her dad as a professor at Central State. When she and her brother Michael – known by his middle name Derek – were growing up, they lived on the campus, which, she said, was “its own self-sustaining community.” The professors and their children lived there and there was an elementary school, a clinic, a country store.”

After that, her dad got a job working with civilian personnel at Wright Patterson Air Force Base. When he retired he and Barbara lived just west of the Wilberforce University campus off Route 42.

Craig and Denise, a fifth grade teacher in Hilliard, built a home next door and they and especially Denise’s son, C.J. Nichols, look after Mickey since Barbara died in 2008 after a battle with cancer.

Denise agreed that her dad’s story – “a gem,” – ought to be told, but Mickey can no longer tell it to you.

He’s been wrestling with ever-increasing dementia for a decade and behind his still-charming smile and sparkling eyes, there is often blank recollection as the past flutters away like so many elusive butterflies.

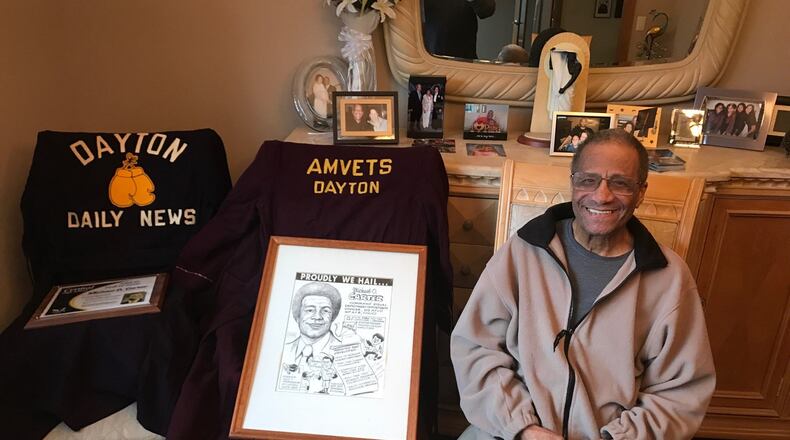

As we sat at the dining room table of his Denise and Craig’s home, he wore his new blue Los Angeles Dodgers cap with “Mickey” sewn across the back. His daughter had pulled out his scrapbooks and some of his citations and awards, but they didn’t seem to register with him.

When I asked about his wife of 52 years – the girl he met at CSU, the woman with whom he raised two children, went with to several Olympic Games, including Atlanta and Sydney, Australia and later was at her side every day in her battle with cancer – he looked at me and shrugged:

“Oh I didn’t know I had a wife.”

Other times, though, he asks where she is and when Denise explains she passed away, he says, “Oh, I should have gone to her funeral.”

As Derek, who now lives in Memphis, put it: “Mom was the love of his life. If he had all his mental facilities now, he would miss her so much more than he does now. It would be hard for him. So in some ways, this is almost a godsend that he doesn’t have to suffer in that fashion.”

My own mother died from Alzheimer’s disease, so I know some of what the person and their family goes through. You embrace the tiny recollections that my come once in a while and you love them how they are.

As Derek put it: “It’s Dad’s world now and we’re just living in it.”

And as Mickey and I spoke, every once in a while something would catch. When we talked about his boxing, he remembered he was a welterweight.

When I asked if I could take his picture next to his scrapbooks, he smiled and, just before I snapped. he suddenly said, “Cheeeeese!”

Finally, when the conversation came to baseball, he shook his head when asked if he had been a pitcher:

“No, not a pitcher.”

Craig quickly scanned a scrapbook article and chimed in: “Second base.”

Mickey shook his head in agreement: “That’s right, second base.”

And with a moment’s silence and a sudden reconnection, he added:

“I was pretty good…oh yeah.”

‘It was tough, but we made it’

Jacci said their life wasn’t easy as they grew up. All four kids were born in New Albany, Indiana and then the family moved across the Ohio River to Louisville a few years later.

She said by the time she was in fifth or sixth grade, her parents had spilt up and she and her three brothers were raised by their mother.

“It was tough, but we made it,” she said.

“Mickey always used to tell us he grew up with one meal a day and normally it was beans and cornbread,” Craig said. “There were no free lunches in school in those days, so his mom packed him peanut butter and crackers. He said he was so ‘shamed not to have anything else that he’d go out on the playground and watch kids play (rather than eat in front of the others.)

“One of the first days he was at Wilberforce, he went with the other players to breakfast and then was confused when the guys started getting ready to go to lunch a few hours later.

“He said, ‘Until then, I never knew people had three meals a day.’”

College was a different world for him and he got joy from even the smallest matters.

As Craig explained: “He told me how he got hit real hard on the football field one day and the other guys helped him up and said, ‘You OK Mickey?’

“He just smiled. His field back in high school was part dirt and cinders and he had a lot of scars from that. He said getting tackled on this field, with the grass, it felt like he had landed on a bed of feathers.”

Just as he excelled in sports, he shined brightly in the classroom and was a regular honor roll student. After graduation – as he worked on his master’s degree through Indiana University – he was offered a teaching job at CSU.

Soon he was able to bring, Jacci and his younger brother Don to the school. And he got his mom a job working on campus.

“I had gone to Louisville Community College two years while I worked at the Grand Theater,” Jacci remembered. “I came to Central State for my last two years and when I got there I thought it was wonderful. Thanks to my older brother, everybody there knew me and treated me well.”

Jacci went on to be a teacher and then a school principal in Cleveland for 28 years.

Although Mickey devoted himself to the classroom, then his job at the base and always his family, he did still embrace one sport.

He regularly played golf with CSU and Wilberforce legends like Ben Waterman, Gaston “Country” Lewis, Jim Walker, Al Baker and one guy, Derek laughed, that he said his dad referred to as “The Pigeon,” for obvious reasons.

Mickey was a good golfer and Craig said it wasn’t until his father was well into his 60s that he could beat him”

“I’d practice like crazy and then go shoot a 74, only to have him shoot a 73. It was like he was taunting me.”

Dedicated to family

When the F5 tornado roared through Xenia and the Central State and Wilberforce campuses on April 3, 1974, Mickey was working at WPAFB.

“I was little and I saw it coming,” Derek said. ‘My mom thought I was kidding, but then she looked. You could see all the way to Xenia ‘cause the trees weren’t in bloom yet and the next thing she’s saying is ‘Boy, get in here…now!’

“We opened up all the doors and windows just like Gil Whitney (the WHIO weatherman) had said. We’d practiced the tornado drills in school, so we stayed safe. And our whole neighborhood stayed in our house that night.”

Much of the rest of the area was destroyed, he said. A nearby neighbor’s house “was leveled… And a young lady coming from Central State, her car was smashed and she perished. So did a handyman named Smitty” who was in a nearby driveway.

Over 80 percent of the CSU campus was destroyed. Four people were killed, 20 were hospitalized. Around Xenia, 28 more people were killed.

“Dad came rushing home and could only get as far as Brush Row Road,” Derek said. “He jumped out of his car and started running. He said all he thought was ‘Oh my God, I hope they’re alive!’

“And finally, there he came in a suit, running for us. That the kind of dedication he had to his family, the kind of grit and focus he showed under pressure —some of it from those days in sports, I’d imagine – that allowed him to run all the way here to us.

“With dad, family was always first.”

Well, almost always.

As I leafed through the scrapbooks, I came upon a clipping from the Xenia Daily Gazette in 1987. It told about Mickey being inducted into the CSU Hall of Fame and included his gushing reaction.

“It’s the singular honor for me,” he said. “It’s the highlight of my life.”

Then he had caught himself just in time:

“Actually, the first highlight is my marriage to my wife Barbara. …This is the second one.”

Just like those days long ago at second base, he managed to make the tough catch.

Like he said:

“I was pretty good …oh yeah.”

About the Author