“Well, this day I got on the bus to go to high school and the girl was on there and she was crying. I asked her, ‘What’s the matter?’

“And she said, ‘Your brother is missing. I just got a letter from one of his soldier friends and he’s been missing for three, four or five days.’ ”

Bucky remembers getting off the bus and numbly trudging back up the lane of the hardscrabble farm from which his family — mom, dad and 10 kids — had tried to eke out a living in southern Illinois.

“I told Mom what happened and it seems to me that that very same afternoon we got the missing-in-action letter,” he said. “I was old enough to drive and Mom said, ‘You better go over to the mines and tell Dad.’ ”

Elvin Bockhorn was surprised to see his son show up at the strip mine that morning in 1950.

“He said, ‘What are you doing here?’ Bucky quietly recalled, his eyes suddenly glistening, his voice momentarily breaking.

“I told him, ‘I got some bad news, Dad — Eugene got killed.’ ”

He said he can still see the reaction of his father, who looked up at the heavens and extended a beseeching hand, as if to say, “Why, Lord? Why us again?”

Eight years before Gene’s death in Pusan, South Korea, the family’s oldest boy — named Elvin after his dad, but known to everyone as Junior — had been killed aboard the USS Cushing in the Battle of Guadalcanal, one of the fiercest naval battles of World War II.

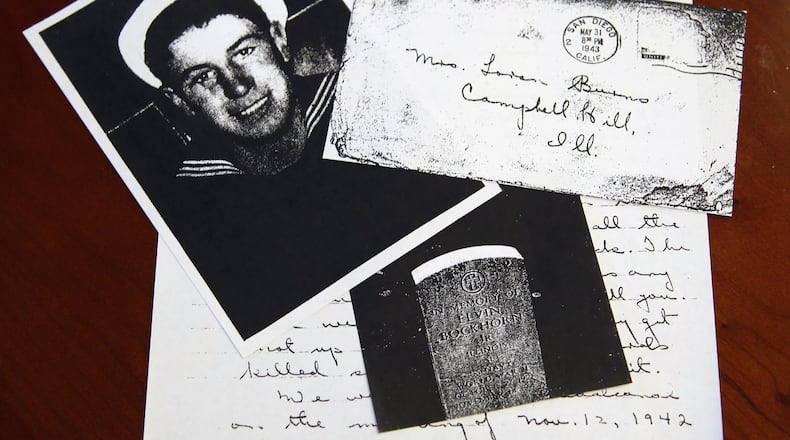

A few months after Junior’s Nov. 13, 1942 death, the family received a five-page, hand-written letter on lined tablet paper from a fellow sailor — R.D. Rough — who had been with him when he died.

“I don’t know just how to write this as I’ve never wrote a letter like this before,” Rough began.

Eight years later Bucky had had similar difficulty when he shared the terrible news of Gene’s combat death with his father.

“I’ll never forget my dad’s look,” he said the other day as sat in the Hickory Bar-B-Q on Brown Street and shared the story few people here know.

Throughout the Miami Valley, Bucky Bockhorn, now 82, is mostly associated with basketball.

He is one of the most beloved and accomplished players to wear a Dayton Flyers uniform. He’s in the school’s athletic Hall of Fame and was a member of the All-Century team. After UD, he played seven seasons for the Cincinnati Royals in the NBA, three of them as the backcourt mate of Oscar Robertson.

For the past 46 years he’s done the color commentary on WHIO’s radio broadcasts of Flyers games.

He and his brothers, Harold and Terry, all of whom played for the 1957-58 Flyers team that finished 25-4 and was the NIT runner-up, hold the distinction of being the first trio of brothers to play alongside each other on an NCAA Division I team. And, in fact, only two other sets of brothers have equaled that feat since.

Yet those who know the Bockhorns the best appreciate the family the most for its military service and the sacrifices it made in World War II and during the Korean War.

Of the seven Bockhorn boys, six — including Bucky — served in the military. Along with the two brothers who were killed, another, Kelsey, saw extensive action in World War II and afterward suffered because of it, Bucky said.

“Back then, when you came from a small rural area like we did, it seemed like everybody got drafted,” he said. “And when your number came up, baby, you were gone.”

A desolate farm

As a child, Bucky first remembers living in the small southern Illinois town of Louisville on the Little Wabash River.

“Then we moved to this farm that was just desolate,” he said. “It was right after the Depression and when we got there, the only thing around was an old mule that had been left.”

There was no other livestock, no farm machinery and no money to put out crops. Elvin and his wife Hulda did what they could to make ends meet and Bucky said some of the older kids got “farmed out” and lived with other families.

“When the war broke out, the two older ones (Junior and Kelsey) immediately joined the Navy,” he said. “As a young child I remember those ‘We Want You!’ signs and I think they wanted to go. Times were hard and they probably couldn’t wait to get into the service.

“Unfortunately I didn’t know them that well. I was younger and they didn’t live at home.”

He said he does recall everyone doing whatever they could to bolster the war effort: “We used to walk to school and I remember picking up cigarette packs along the way and taking out the tin foil because it was supposed to go to the war effort.”

While he knew little of his two older brothers, he does remember being fascinated when one of them came home on leave in uniform.

He opened up a folder he’d brought with him and pulled out a photo of Junior and Kelsey in their Navy uniforms and sailor caps, sitting side by side in a tavern, smiling, as they shared some beers.

“For Christ’s sake, look how young they look,” he said proudly as he studied the picture and smiled. “I really wish I knew Junior. They say he was one hell of a guy.

“When they enlisted, they promised them that they’d always be together. Well, that was b.s. They separated them right away.”

Yet, as it turned out, that was good for Kelsey.

Deadly consequences

Junior ended up on USS Cushing, a 1,465-ton destroyer that was ordered to the South Pacific in mid-1942 to join the campaign to hold Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands.

As R.D. Rough wrote in his letter to Bockhorn’s sister, Anita:

“We went into Guadalcanal the morning of November 12, 1942 about one hour before daybreak. We took in some Marines on transports and started unloading them. About 12:30, right after dinner, 27 Jap torpedo planes attacked us.

“Our force got them all without any damage to us. We finished our job about 10 or 10:30 that night. We were just about ready to leave when we got word that the Japs were coming in.”

In the wee hours that next morning the U.S. force of five cruisers and eight destroyers ran up against a much larger Japanese fleet that included two battleships, five cruisers and 11 destroyers whose target was to destroy the Marine Corps airbase — Henderson Field — at Guadalcanal.

The Cushing was at the head of the outgunned U.S. column and barreled right into the center of the Japanese formation, opening fire in the unusually close quarters.

As described by the Destroyer History Foundation, the USS Cushing “received several hits amidships, resulting in a gradual power loss, but she determinedly continued to fire her guns at the enemy, launching her torpedoes by local direction at an enemy battleship (Hiei). Fires, exploding ammunition, and her inability to shoot any longer made the ‘abandon ship’ order unavoidable at 0230.”

The Cushing eventually sank and about 70 of her men were killed or lost.

Junior Bockhorn was one of them.

“Your brother was on my gun on the Cushing, gun two,” Rough wrote. “All our other guns were out of commission except gun two.

“They gave us the order to abandon ship, as the ship was burning, sinking and the magazines and fuel tanks were exploding. Gun two was the highest on the ship, so our job was to protect the other men from enemy fire until they got all of them to over the side.

“But just then this cruiser turned four big search lights on us. Out of 28 men on the gun, only eight were alive then. Then somebody started firing at us from behind (too). One big shell hit the gun and blew it up. That’s when your brother was killed…

“Your brother died right away. He got hit hard, but didn’t say a word. He knew the ship gave the Japs a bad time and that was all that counted.”

Only four of the 28 men on the gun survived and three, including Rough, had been severely wounded.

The Japanese sank or destroyed all but four U.S. ships. Two American admirals were among the 1,439 forces killed. In turn, the Japanese lost several ships, including the massive Hiei, and some 800 troops.

Although both sides suffered deadly consequences, the Americans were recognized for a strategic victory because the bombardment of Henderson Field had been prevented. In the process, American morale was buoyed and the myth of Japanese invincibility was left tattered.

In the early 1990s, the severely damaged Cushing was discovered resting almost upright a half-mile below the surface of Iron Bottom Bay — so named because it holds the wreckage of so many U.S and Japanese war ships — southeast of Savo Island.

Junior Bockhorn is remembered by a grave marker at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines.

Bucky said Kelsey witnessed a lot of the same brutality of war and “it destroyed him when Junior got killed.

“My brother Harold told me Kelsey was a real workout freak and he used to fill up a gunny sack with wheat, cut rubber strips from inner tubes and wrap them around his hands and then punch the hell out of that bag.

“He was a tough SOB and when he got home it seemed like he got in a fight every night. He worked on the big barges that went from Texas to New Orleans and he was getting into it with the Cajuns all the time.

“We didn’t know it then, but I think it was that PTSD or whatever back then.”

Continued to serve

As for Eugene, Bucky said, “He was the hard luck guy in the family. He never went to high school, didn’t like the farming and went through a bunch of odd jobs.”

But when he joined the Army during the Korean War, Gene found his calling as a medic.

The family received in 1999 a letter from Bernard C. Neel, also of the 25th Infantry Division, who had been with Gene at Pusan.

“We had made a pact that if something happened to one or the other, we would contact the other’s family and let them know what happened,” he wrote.

Neel said he had been unable to locate the family and also admitted he had struggled mightily with the death of his friend: “For all these years I have not been able to talk about it without getting very emotional.”

He wrote of Gene’s courage and how he’d always jump up when someone called for a medic.

“He told us Gene was one brave SOB,” Bucky said. “He said he got killed jumping in a foxhole to save somebody and they threw in a grenade.”

Bucky said he faintly remembers the train coming into Campbell Hill, Illinois, and delivering Gene’s casket.

Yet, even with two devastating losses, the Bockhorns continued to serve.

Harold ended up in the Air Force, another brother, Carroll, was sent to Korea at the war’s end and Bucky got drafted into the Army following his freshman year at UD. He was in boot camp in Washington when the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed.

He said the family of his wife Peggy — they’ve been married 57 years — was just as committed to the U.S. military effort:

“Her brother was in Korea and her four uncles — all tough little SOBs — they all served in World War II. One was on a belly gunner on a plane and another one, Joe, was a paratrooper with the 101st Airborne and jumped at D-Day and in Holland.

“Back then, that’s how it was,” he said. “You served your country.”

‘About my brothers’

Although he said his dad “didn’t tolerate sports, he thought they were a waste of time when you could be working,” Bucky said he did manage to put up a homemade hoop in the chicken yard at the farm and had to beg his dad to go to high school basketball practice twice a week.

That led to a stellar career, first at Trico Consolidated High, where his number is retired, then as a 6-foot-4 swingman who started on three straight NIT teams at Dayton, including a senior season where he was a co-captain and team MVP, averaging 10.8 points and 12.4 rebounds a game.

A third-round pick of the Royals, he played in 474 NBA games, averaged 11.5 points, 4.7 rebounds and 3.5 assists over his career and made his bones as a tough-nosed defender who would take on the opposition’s best player, whether he was a forward or guard.

Yet the other day when pressed on his basketball exploits he shook his head: “I don’t want this about me and my basketball. This is about my brothers.”

And on this Memorial Day weekend that’s how it should be.

“As a kid growing up I remember how proud I was of my older brothers,” Bucky said. “And all these years later, I still am.

“So you can bet your (butt) I’ve got my flag out there flying this weekend.”

About the Author