So, Dombrowski told him that outfielder Curtis Granderson would be available.

“I said, ‘I’m in,’ so we started talking,” Cashman said.

About seven weeks later, a three-team trade involving seven players was completed. Among the components of the deal: Granderson became a Yankee.

The baseball landscape is changing, with an influx of young executives, many armed with advanced degrees and analytics backgrounds. It would seem that a pair of veteran hands like Cashman and Dombrowski, who have been trading with each other for nearly 20 years, would have plenty of reasons to continue doing so.

But one thing has changed in their relationship: Dombrowski is now the president of baseball operations for the Boston Red Sox.

“The Yankees and Red Sox — we don’t do deals,” Cashman said.

When Cashman was reminded that he had consummated one trade with the Red Sox since he became general manager in 1998, he had to be prompted that it was midway through the 2014 season, when he acquired Stephen Drew and cash from the Red Sox for Kelly Johnson.

“Did I get Kelly Johnson from those guys?” he said before being reminded that it was the other way around.

Dombrowski, who has a lengthy history of making bold and creative trades in his 27 years as a general manager in Montreal, Miami and Detroit, conceded that his sixth trade with Cashman — another three-team deal that sent pitcher Shane Greene from New York to Detroit so that Cashman could acquire shortstop Didi Gregorius from Arizona — could be their last for a while.

“I would assume that would affect us some,” said Dombrowski, who was hired by the Red Sox after being fired by the Tigers in August.

It was the same for years when Theo Epstein was the Red Sox’s general manager. Though he and Cashman had an easy relationship, occasionally sharing the stage at baseball symposiums at small colleges in the Northeast, Epstein said that only once, early in his tenure, did they talk about a trade — and it was half-joking at that: Shea Hillenbrand for Nick Johnson.

“But nothing ever came of it,” he said.

Epstein, now the president of baseball operations for the Chicago Cubs, said it was similar to his dealings with his current rival, the St. Louis Cardinals.

“We have less dialogue with the Cardinals probably than any other team, and in Boston we had less dialogue with the Yankees than any other team,” Epstein said. “It’s just common sense. Obviously the key is to focus on what you’re getting back for your club, but it would do a lot of harm to the organization if the deal backfired on you and hurt your own club and helped your rival beat you on the field at the same time. It’s sort of a double penalty, so you have to be pretty fearless to embrace that.”

Baltimore Orioles general manager Dan Duquette said of the perils of trading within the division: “If you’re not right on the transaction, you’ve got to look at your mistake for 18 games a year.”

Some places, though, are more perilous than others. The American League West seems to be an especially welcoming place, with the teams separated by great distances and the fan bases and media markets not so rabid. Jerry Dipoto, recently hired as the Seattle Mariners’ general manager, made trades with every division rival in his three and a half years as the Los Angeles Angels’ general manager.

“In the Northeast, in the major media markets, when you’re making trades, one of the elements you’re looking at a little more is risk,” Dipoto said. “You take note of it.”

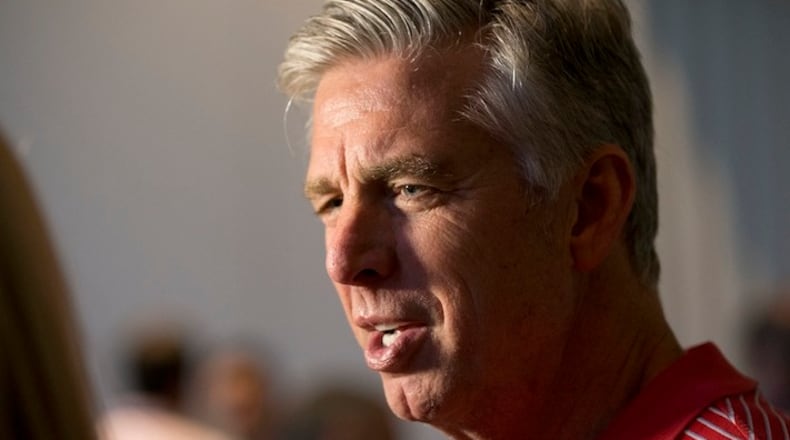

It was easy, then, to take note that when each team’s baseball executives were made available to the news media on Tuesday and Wednesday, Cashman and Dombrowski were among the most popular figures.

At this time last year, Cashman was desperately seeking Gregorius, the shortstop the Yankees had targeted to replace Derek Jeter. But after two months, he could not find a match with the Diamondbacks, so he called Dombrowski, who had told him he liked Greene.

“I said, if you can get me Didi, I’ll give you Shane,” Cashman said. “I don’t want to do it, but I’ve got no choice. I don’t have a shortstop and this is the one I want. So, within 48 hours, Dave called me back and said, ‘I’ve got him.’”

While the trade looks to have worked out more favorably for Cashman, some others have not gone that way. Dombrowski landed the future Cy Young Award winner Max Scherzer and center fielder Austin Jackson in the deal for Granderson, and picked up Carlos Pena and Jeremy Bonderman in a three-way deal with Oakland that sent Jeff Weaver to the Yankees.

And in what Cashman once termed his greatest regret, he sent third baseman Mike Lowell to the Marlins for three prospects who never panned out.

“In Brian’s case, we’ve known each other for a long time,” Dombrowski said. “It’s very easy for me to pick up the phone. He’s very direct, he’s very open — the same thing for me. There’s a comfort zone there.”

Cashman said that type of rapport was important.

“What makes the world go round is definitely relationships,” he said. “That’s why big politicians that are running big governments are always trying to develop good relationships, especially with states they haven’t typically gotten along with over the years, just trying to cultivate better atmosphere to find good will.”

In a Yankees-Red Sox rivalry that has, at times, been defined by ill will, with executives portraying it as good versus evil, the longstanding relationship between Cashman and Dombrowski should ensure some degree of civility — perhaps even a continuing dialogue.

Just don’t expect them to hammer out any trade agreements.

About the Author