Jack London State Historic Park

Where: 2400 London Ranch Road, Glen Ellen

Hours: 9:30 a.m.-5 p.m.

Cost: $10 vehicle entry fee

Information: jacklondonpark.com

GLEN ELLEN, Calif.—Rain fell. Nothing major, certainly not on the level of an Old Testament gully washer. Just a steady, spitting splatter of linked hydrogen and hydroxyl ions that turned the ground squishy and made you want to nominate the inventor of Gor-Tex for a Nobel.

This weather, however, apparently was inclement enough to call off a full Saturday of activities — photography classes, tours of ruins, a poetry reading — at Jack London State Historic Park, washing out a small portion of the yearlong celebration marking the centennial of the writer’s death and internment under a large volcanic boulder at his spread in rural Sonoma County.

Perfectly understandable, really. Still, doesn’t it make you wonder what Jack London would’ve thought about letting a little rain spoil your experience?

I mean, c’mon, this was a famously roguish writer whose wanderlust and thirst for adventure sent to him to far-flung locales on the high seas and frozen tundra, champing a cigar, chugging Glenlivit and scribbling down impressions for the reading public. You think London would’ve let a little dampness stop him? Think he cared if his trouser cuffs got wet and his shiny boots sullied? Ha, you don’t know Jack!

I said as much — albeit maybe not so embroidered with mock passion — to Tjiska Van Wyk, executive director of the park, in a subsequent telephone conversation. She merely chuckled, kind of dryly. But she seemed to take the ribbing in the good-natured spirit in which it was intended.

Weather permitting, the park is going all out in 2016 to celebrate all things London. Each month, docents and a passel of nature and historical experts will lead tours and give talks and oversee hands-on activities, not only highlighting London’s productive career (more than 50 books between 1900 and 1916 alone) but featuring his waning years as a writer-slash-gentleman farmer on the 130 acres he purchased as a restorative home base after his peripatetic “Call of the Wild” exploits.

Van Wyk said the events will allow visitors to “delve into London’s legacy” in many ways: nature hikes, wildflower gazing, plein air watercolor painting, alfresco piano concerts, book-group discussions, not to mention the annual summer “Broadway Under the Stars” musical theater series.

“What we’ve been saying is that we want to ‘Bring Jack Back,’” Van Wyk said. “By that, I mean, in the past he always used to be on the required reading list for all school kids. Now he’s on the ‘suggested’ list. We want to keep him prominent. We want to lift his profile not just (as an author), but we find that people don’t know about what he was trying to do here (in Glen Ellen) with sustainable land practices. There’s a lot more to (London) than you’d think.”

The historic park is bisected by two parking lots just past the entrance kiosk. Park in the upper lot, and you can explore the remnants of the work of “Farmer Jack” at what he called “Beauty Ranch.” Park in the lower lot, and you can experience “Literary Jack” — his gravesite, the remains of the grand Wolf House that burned to the ground during construction and his widow’s “House of Happy Walls” that now is a museum chock full of Londonalia.

The upper park is geared mostly for those wanting to explore the outdoors. Check out what’s left of the grain silos, smoke house, stallion barns, manure pits, the winery and distillery and the elaborate “Pig Palace,” a circular feed house attached to 17 pens featuring a roofed sleeping area and fenced outdoor “runs” for London’s porcine boarders. An informational sign says that Sonoma County farmers had great sport in making fun of London’s lavish pig sty, but supporters are quick to note that he was ahead of his time in advocating “free-range” livestock raising.

Venture farther west, slightly more than half a mile, and you’ll come upon London Lake, a 5-acre man-made body of water, with a stone dam, at the base of a 6-mile trek up a winding fire road leading to the 2,463-foot summit of Sonoma Mountain. The first part of the trail is lush and shaded, canopied by Douglas fir, redwood, manzanita and oak. Near the summit lies grassy slopes with the payoff being a gorgeous view down upon what the native Miwok people called “The Valley of the Moon.” (London titled one of his novels, about a proletariat Oaklander going back to the land, “The Valley of the Moon.”)

You don’t have to imagine London tramping through this hilly expanse carved with trails because he wrote fictionalized accounts of it.

This from Chapter 36 of his highly autobiographical, alcohol-soaked 1913 novel, “John Barleycorn”:

“I ride out of my beautiful ranch. Between my legs is a beautiful horse. The air is wine. The grapes on a score of rolling hills are red with autumn flame. Across Sonoma Mountain wisps of sea fog are stealing. The afternoon sun smoulders in the drowsy sky. I have everything to make me glad I am alive.”

It was not all vigorous horseback riding and diligent agrarian chores for London on this side of the property. No, just west of the manure pit lies the cottage where London composed scores of novels from 1911 to 1916 before dying on the front porch that November under circumstances (suicide? overdose? tropical diseases?) still debated by scholars but listed as “gastrointestinal uremic poisoning” in official park literature. What’s not debatable is that London found artistic inspiration at the cottage. He wrote looking out on a massive, gnarled oak tree and, according to some reports, occasionally would sit under the tree with pencil and notepaper poised.

The house is worth seeing, even if it now is mostly a skeletal volcanic-rock frame of one man’s dream. Architect Albert Farr spent years building the four-story, 15,000-square-foot, 26-room house that cost $80,000 to construct. A month before London and second wife Charmian were to move in in 1913, the house was gutted by flame, combusted spontaneously, forensic fire experts believed, from the discarded linseed oil rags of workers. London vowed to rebuild; he died at 40 before workers could even start.

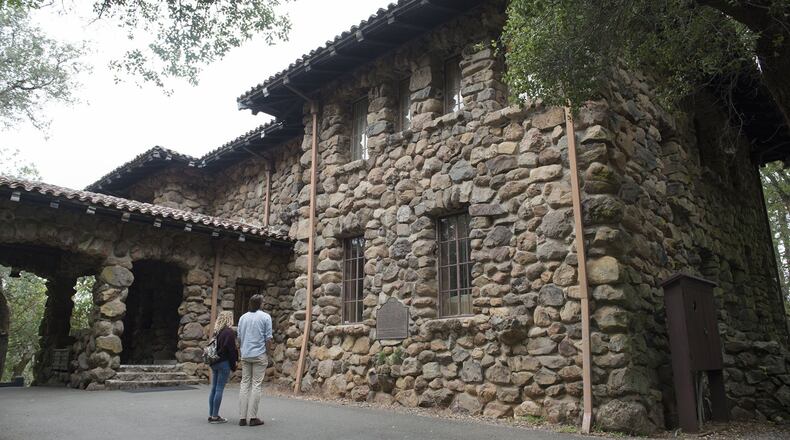

The more interesting part of the lower park, to bookish types, is the museum housed in the House of Happy Walls, which is the fieldstone home with a Spanish tile roof that his widow built after London’s death. Charmian London lovingly preserved all of Jack’s possessions — souvenirs from the Yukon and other journalistic adventures, even his roll-top desk and the Dictaphone he used to plot out his works.

Many of his papers and correspondences are on display. You can read, pre-“Call of the Wild” and “White Fang” fame, examples of the rejection letters London received from San Francisco newspapers. (Example from the Chronicle’s M.H. deYoung: “Owing to a pressure of other matter upon the columns of the Chronicle, I am unable to use the manuscript … ”)

About the Author