“Imagine,” Fred Rogers said, “what our real neighborhoods would be like if each of us offered, as a matter of course, just one kind word to another person.”

Now, Congress, at the request of the Trump administration, has withdrawn $1.1B of funding over the next two years to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

The cuts have nothing to do with the value the stations provide. Rather, it’s another act of retribution against perceived liberal bias. “Democratic paper-pushers masquerading as reporters don’t deserve taxpayer subsidies, and NPR and PBS will have to learn to survive on their own,” White House principal deputy press secretary Harrison Fields told Politico.

You know what? He’s partially right. The liberal bias stuff is a nice catch phrase that fires up the base, but is factually inaccurate. In just one of many examples, PBS has done reporting on how U.S. Sen. Mitch McConnell has reshaped the Supreme Court and the federal judiciary.

But Fields is right that public broadcasting needs to figure out how to get along without public money that will become harder to come by as the government grapples with debt.

In 1967, Congress created the Corporation For Public Broadcasting to help fund commercial-free educational programs. If you haven’t read the act, you should, because it’s an example of a well-thought-out piece of bipartisan legislation.

But as time went on, CPB grew — a lot. There were 128 member stations in 1970, and more than 10 times that today (1,500).

This leads to questions that should be the focus of the debate. Did CPB grow too fast? Did some of its stations become too reliant on federal funds? Does the country need 1,500 public media stations?

PBS gets about 15 percent of its money from the feds and NPR, 2 percent, according to the New York Times.

The bigger stations will likely be OK since they can tap into larger donor bases. It’s the smaller stations that could be in trouble. WYSO in Yellow Springs could lose $600,000 over the next two years. Rural stations, often located in Republican strongholds, might have to close.

Public Media Connect, the Cincinnati-Dayton partnership, has a steeper hill to climb as it stands to lose $2.6M annually.

But there’s hope. Donations to stations have increased since the news of the cuts. Look at The Summit FM, the Mahoning Valley nonprofit public radio station that plays only music. It lost $130,000 in federal funding, a big chunk of its $1.4M annual budget. The station took immediate action and did a weekend fundraiser that brought in $165,000 from 400 donors, enough to cover the shortfall.

Summit shows that if people want the content, they’ll pay for it. It’ll be up to the stations to show their value and convince the market to support them. That’s no different than in any other business.

From a selfish perspective, I want public broadcasting to survive because I have friends and family — all excellent, award-winning journalists — working at some of those stations. Their efforts provide investigative and other reporting that can be hard to come by as media resources shrink.

But from a practical perspective, the educational, cultural, and historical content PBS provides is still the best. Our communities, especially in rural areas that lack content options, would be worse off.

Now, CPB must figure out how to provide its service without government help, and that’s not a bad thing. It’ll ensure public broadcasting’s independence from hostile lawmakers and the ability to provide content without looking over its shoulder.

We’ve already seen how the government can crush media that relies on it for funding, as it did to Voice of America. The government has inadvertently done public broadcasting a favor by removing the funding chains.

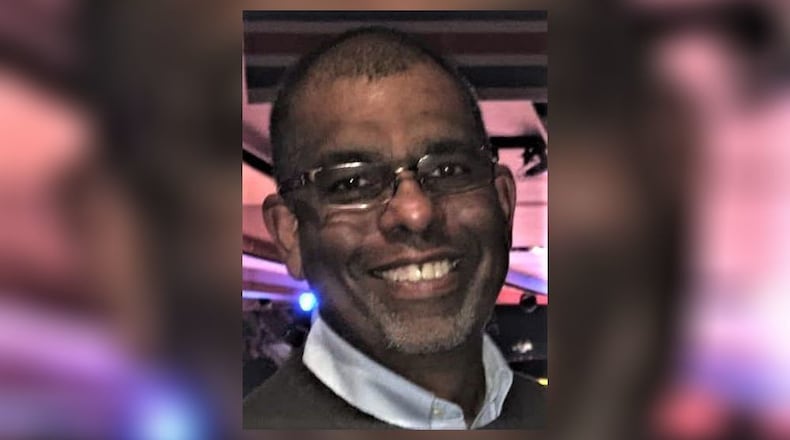

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday.

About the Author