Some considered Bob an oddity, too. A Vietnam veteran, Bob sometimes twitched a little, lost his train of thought, and had bad nightmares. Explosions. Screams. Images he’d never talked about, not in detail, anyway.

I think that’s why he liked laying line for catfish in a creek near his house. We would lay the line with thick, heavy hooks late in the evening, and return to the creek just as the sun came up to collect our haul. Bob didn’t sleep much when we did that. He liked it that way. Nightmares don’t come when you’re awake.

Back at his house, we’d clean the fish his wife would later cook. It was a simple meal that wasn’t due to all the work from getting the catfish from the creek to the plate. Bob always sat at the head of the table. His wife always served him. They prayed before every meal, and Bob saluted the flag that flew in front of his house.

Bob and I fished at least twice a week, sometimes more. The friendship of fishing meant the most to Bob when he could talk about whatever was on his wandering mind. Sometimes he’d discuss his wife and kid, or the difficulty of being poor and surviving on disability payments. A staunch conservative, he ranted about how liberals were killing the country. We need more Reagan, less Carter, he would muse.

After two years in Vinita, I took a newspaper job in Tulsa, some 64 miles southwest. We vowed to stay in touch, and we did.

Then, the bottom fell out.

I covered cops from 4 p.m. to midnight and picked up a 15-hour-a-week job during the day for a little extra cash. Reporters didn’t make much back then.

Bob showed up at my part-time job one day, looking like he had walked through the bad side of hell. He was driving his old, beat-up brown cargo van, the kind with a ladder that went to the roof with smoke spewing out of the tailpipe. He had lost a lot of weight, and his cheekbones protruded through his face. His eyes looked like they bulged out of their sockets. He hadn’t shaved or bathed in lord knows how long.

The van was piled high with trash, and he slept on a filthy twin mattress crammed in the van bed. The stench ripped through the humid Tulsa air like dead fish in a dump.

He was incoherent. He said his wife had thrown him out, tired of the mood swings and demands that she serve him. He had no place to go, no money, or friends. He was utterly, completely lost.

I gave him enough cash to gas up his van and get food. I asked him to return the next day to give me time to find a more permanent way to help him.

He said OK. I shook his hand and patted him on the shoulder.

I never saw him again.

On Memorial Day, we honor those who serve, and we should. But we should also remember the Bobs of the world, veterans who returned home broken and forgotten.

The NIH says up to 16% of veterans returned from Afghanistan and Iraq with a mental health need. Vietnam vets, compared with non-veterans, had more than nine times the risk of PTSD, double the risk for depression, and six times the risk of psychological distress, according to the Department of Veteran Affairs.

Worse, half of the Vietnam veterans never received the mental health care that could have helped them, according to the Department of Veteran Affairs.

These veterans kept us free. We shouldn’t let them fall through the cracks.

We shouldn’t let them become Bob.

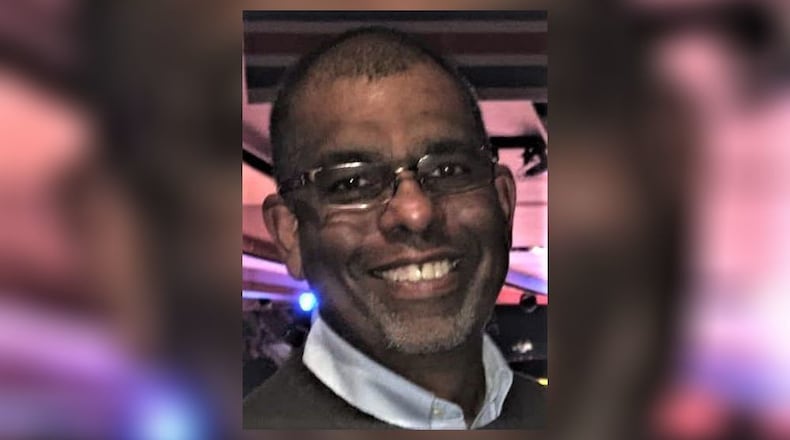

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday. He can be reached at raymarcanoddn@gmail.com.

About the Author