I also remember how Junior would sometimes twitch between snores, and how my father would go to him when the twitching became shaking, and how Junior would wake up screaming.

My father served in Korea, as did Junior, and they both saw combat. It wasn’t until years later I understood Junior suffered from the effects of the war.

The United States fought in the Korean War between 1950 and 1953. Of the 6.8 million Americans who served, 54,200 died, with 33,700 of those killed in battle, according to the Department of Veteran Affairs.

The veterans who survived and came home suffered from all sorts of mental health issues, but they were poorly diagnosed at the time.

The research paper “Psychiatry in the Korean War: Perils, PIES, and Prisoners of War” details how soldiers were treated based on the WWII principles of “proximity, immediacy expectancy, and simplicity.” In short, these soldiers received psychiatric treatment and rest before going back to the front lines.

When veterans came back, especially the men, they were expected to conform to societal expectations of the 1950s and maintain their stoicism. As a result, research shows few veterans sought treatment for what was then called shell shock, battle fatigue, or soldier’s heart.

Today, we would treat these returning veterans for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

It wasn’t until 1980 that the American Psychiatric Association added PTSD as a mental health disorder, well after my father and Junior came home.

I had no idea what Junior was going through, and as I got older, I wondered if my father’s mental health issues stemmed in part from his service (I’ll never know; he died in 1975 following multiple heart attacks).

But I do know that we should do everything we can to take care of our veterans, and we don’t. The Veteran’s Benefits Administration has a backlog of nearly 300,000 claims, which forces people who fought for and defended this country to wait an inexcusably long time for the benefits they deserve. (The VA defines a backlog as a case pending for more than 125 days).

Some historians believe the first Memorial Day gathering happened on May 1, 1865. That’s when some 10,000 people, mostly the formerly enslaved and abolitionists, placed flowers on the graves of 250 Union Soldiers in Charleston, S.C.

Since then, Memorial Day has become the primary day to honor those who have died in service to America. We owe them a debt we can never repay.

Let’s also remember those who served and came back with life-long trauma that stayed with them until they died.

I don’t remember the last time I saw Junior, how the rest of his life turned out, or how he died. I’ll always remember my small father (5′7 and about 140 pounds) holding this shivering hulk of a man whose outward strength hid his inner turmoil.

On Memorial Day, I’ll remember those who died. But I’ll honor those who remain alive but tormented.

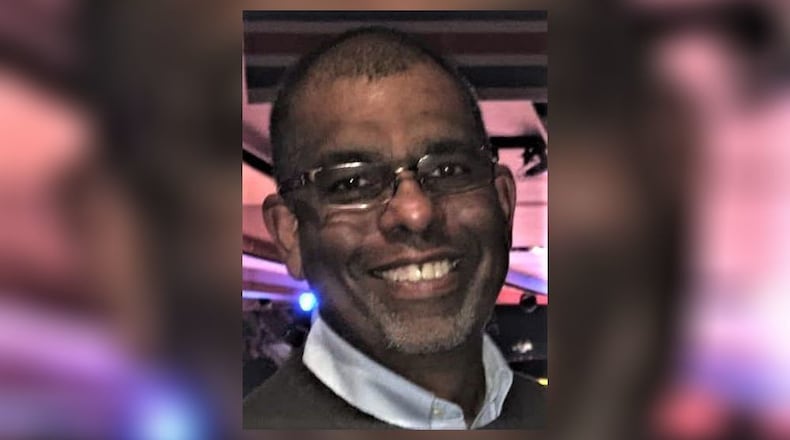

Ray Marcano’s column appears on these pages each Sunday.

About the Author