At the time of her initial diagnosis, Matzik’s mother, June Matzik, was advised to take her daughter home and keep her comfortable. But Matzik did not die, and it wasn’t until she was 15 years old that she received the correct diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy type 2. At that time, she had been going to the Alfred I. duPont Rehabilitation Hospital for Children in Delaware for care.

“I had a spinal fusion and that’s when they correctly diagnosed my condition,” Matzik said. “I needed the operation to save my life since I only had about 10% breathing capacity.”

After the surgery, Matzik was put on a ventilator and, with her breathing much improved, her stamina increased. She knew she had many obstacles to overcome, but managed to remain mobile by choosing to live her life in a reclining position.

“When they did the spinal fusion, the curvature of my spine was so bad that they couldn’t fuse one vertebrae and I almost died during the procedure,” Matzik said. “I had the option of going back to surgery or to try to adapt my life to a lying-down position.”

Matzik opted not to undergo such a risky surgery again. She adapted to her life in a reclining wheelchair and started looking for colleges that could accommodate her needs.

“I really didn’t have a lot of thought about it at the time because there wasn’t anyone in my family who had gone to college,” Matzik said. “When I was at duPont, I had a fabulous teacher who convinced me I had the potential to go to college and helped me finish high school and take college entrance exams.”

Matzik wrote to 89 colleges and universities across the country, letting them all know she had a 4.0 GPA in high school, but also describing her disability and her needs in detail. Most of these responded that she was too much of a liability to live on campus.

“Wright State University was the only one that said they could accommodate my needs,” Matzik said. “They said if I could come to Ohio, they would meet with me.”

Matzik’s mother was surprised when her daughter told her about Ohio and had concerns about it being so far from home. But in 1989, Matzik and her two full-time caregivers, along with her mother, drove to Dayton to meet with the director of disability services at Wright State.

“Because of my ventilator and trach, I’m considered skilled care,” Matzik said. “I had some difficulty getting the state of Pennsylvania to fund my education because of the risk involved.”

In the end, Matzik was able to attend Wright State after a year’s delay and started college in 1990. The fight to get this funding marked her first major advocacy campaign as she worked with local politicians to back her cause. Though she continued at Wright State for three years and maintained a 3.8 GPA, funding was pulled during her final year and she went back home to fight once again so she could finish her degree.

“It took five years to get my bachelor’s degree in rehabilitation counseling,” Matzik said.

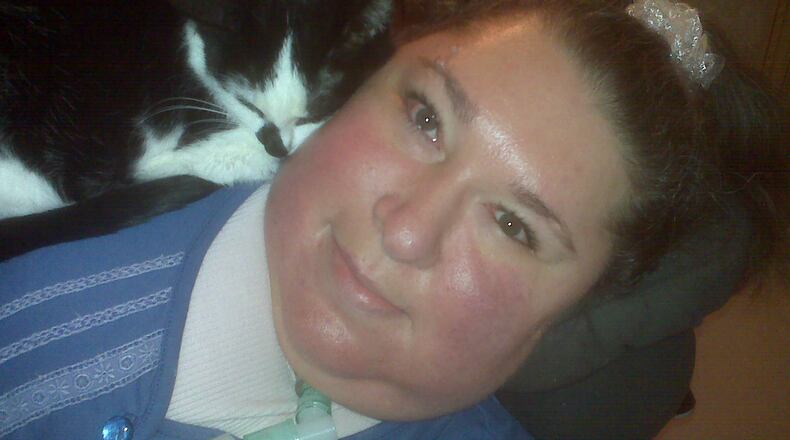

Matzik described her time at Wright State as “amazing.” The university was at that time, and continues to be today, one of the top in the nation for inclusivity and disability services. As a result, she was able to gain her independence and decided to make the Dayton area her home. She and her life partner, Alan Cochrun, have lived together in their home in Fairborn since 1996.

But because of her many fights to gain that independence, Matzik got to know politicians and state officials and realized that her calling was to help other disabled people and advocate for their rights. Today she serves as the education and advocacy specialist for the Access Center for Independent Living (ACIL). She also serves on six state Medicaid committees.

“Accessibility isn’t really a right unless you know it’s your right,” Matzik said. “There are so many loopholes in the law, and you need help understanding it. I think you have to believe that you can do something but for me, it’s also about the people that were placed in my life that helped me see the path I needed. It’s about believing in yourself and knowing how to tap into resources.”

For more information, visit acils.com

Contact this contributing writer at banspach@ymail.com.

About the Author