Before Fairchild set out on his mission, American agriculture was in a rut, according to Daniel Stone, author of “The Food Explorer: The True Adventures of the Globe-Trotting Botanist Who Transformed What America Eats.” People ate meat, particularly pork, cheese and bread. Fruits and vegetables were rare, and often viewed with suspicion.

Then came Fairchild, who visited more than 50 countries by boat and sent back thousands of seeds and cuttings. Some could not be grown efficiently in American soil, some never found a wide American audience. But an impressive number of others hit their mark.

“You can see his legacy when you walk into a supermarket and you see mangos that are native to the Philippines, when you sleep on sheets that are made of Egyptian cotton that he brought to this country, when you eat types of citrus, oranges and lemons, that are native to China, when you drink American beer, because of the hops that he brought at the end of the 19th century,” Stone said from his home in Washington, D.C.

It’s not just mangos, Egyptian cotton, some varieties of citrus and hops that were better for beer than the types already being grown here. Fairchild also introduced avocados to these shores. And dates. And pistachios. And cashews (they were popular but could not be grown here). And soybeans. And red seedless grapes. And kale. And citron.

The story of how Fairchild came to get the citron cuttings is one of the most dramatic in a book full of dramatic stories. He was just 25 and alone in Corsica, with no official papers and only slight knowledge of French. He was arrested on suspicion of being a spy of some sort — which is kind of what he was. A culinary and agricultural spy.

“He was an economist, he was a botanist, he was a traveler, an adventurer, he was a diplomat. He really combined all those skills to have a transformative effect on the country,” Stone said in a phone interview. Stone will be at Left Bank Books on March 14 to discuss his book and the life of Fairchild.

Fairchild had both the people skills and the knowledge to do the job that he essentially invented. He had to know which plants might be beneficial to Americans, which could possibly be grown here and which might find a receptive audience. He had to know the weaknesses of plants grown in the United States so he could recognize the potential of a different variety grown elsewhere. He had to know how to cajole farmers, most of whom had never seen an American before, into allowing him to take a cutting or send back some seeds.

And he had to have the courage to go into dangerous lands (there was a reason Fiji was called the Cannibal Islands, though the tradition of eating human flesh was dying out by the time Fairchild brought them their first encounter with ice) and to risk disease. He came down with a case of typhoid fever in what was then called Ceylon — just after leaving a boat on which a child had died of cholera — and his mentor, sponsor and frequent traveling companion Barbour Lathrop suffered a near-fatal case of yellow fever.

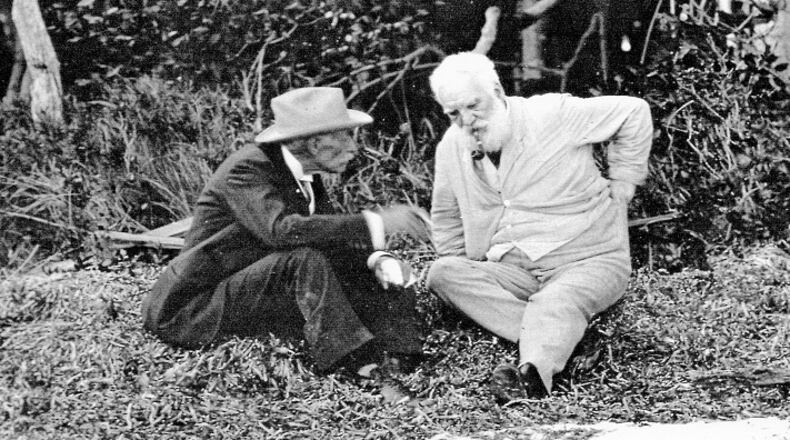

Lathrop, who insistently wends his way throughout the book, is almost as interesting a character as Fairchild. Born into a real estate fortune, he spent most of his days restlessly traveling around the world, telling and embellishing stories of his adventures to anyone who would listen and some who would not.

Lathrop provided the money and companionship for Fairchild’s initial voyages and was easily the most important person in his life until Fairchild met and married his wife — who was, almost inevitably for a life this well-lived, the daughter of Alexander Graham Bell.

Once he was married and had children, Fairchild stopped his incessant traveling. Still, Stone said, “he had even more impact in the second half of his life,” because he recruited a few young men to continue his work, and they sent back even more seeds and cuttings that proved beneficial to American farmers and cooks.

One of these men made his biggest splash with a lemon he was originally told was just ornamental. The man, who had briefly worked at the Missouri Botanical Garden early in his career, tasted it and was amazed by the flavor. It was sweeter than a lemon and more tart than an orange.

The man’s name was Frank Meyer.

About the Author