She accomplished many firsts for blind people during her lifetime and spent 40 years teaching in Dayton Public Schools, never ceasing to look for more personal knowledge along the way.

Early life

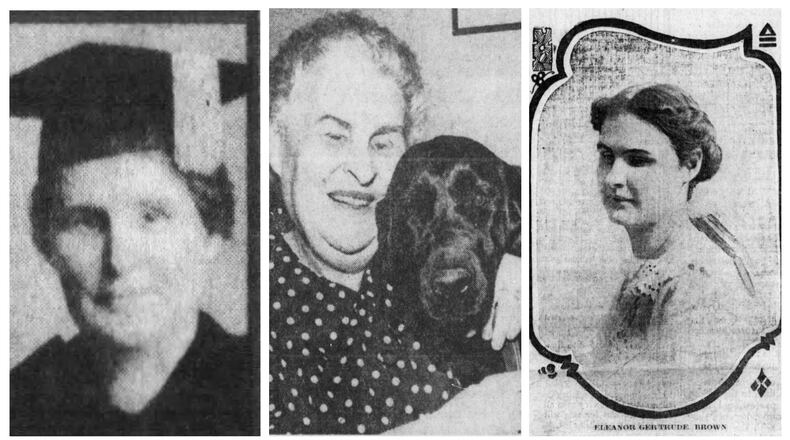

Brown was born in Dayton in 1887. She was partially blind at birth and totally blind by the age of 11.

Brown was versed in the Braille system of reading and writing at a young age, but also learned to type, cook, sew, knit and weave.

She attended the Ohio State School for the Blind in Columbus for 14 years and graduated from there in 1908 at age 20.

Brown then took a job earning an average of $7 a week doing work in a local paper box factory. She saved up $94 and used it to attend Ohio State in 1909.

Credit: Lynch, Gregory

Credit: Lynch, Gregory

She did so well in her first semester that President William Thompson listed her as a beneficiary of a scholarship fund for specially successful and needy students. The story of her success in college reached newspapers, resulting in the Federation of Women’s Clubs of Columbus contributing to her tuition during the remainder of her time there.

Gov. James M. Cox and others helped change a law to provide funding for “readers” who read text books to blind people attending higher education in Ohio. Before that, Brown paid for readers.

She had been warned that no blind person had ever graduated from Ohio State, but that didn’t stop her from getting her Bachelor of Arts degree in 1914, after just 3.5 years.

A decade later, in 1924, Brown went on to earn a master’s degree at Columbia University, where again she was the first blind person to do so.

A Doctor of Philosophy degree followed in 1934, also from Columbia University as the first reported blind person to earn a doctorate degree in the U.S.

She wrote her doctoral dissertation on poet John Milton’s blindness.

Teaching career

Brown was a teacher in the Dayton Public Schools system for 40 years.

“I was confident I could teach the subjects at Steele High, but keeping discipline in classes of obstreperous teenagers — that was the question mark,” she said later. “The answer came in simply being one jump ahead of my students.”

At Steele high school, she taught German, Latin and world and American history for 25 years.

When Steele closed in 1940, she continued at Wilbur Wright High School until retiring in 1952. After retirement she occasionally worked as a substitute and night school teacher.

Some of her former students included Frank Stanton, former head of CBS, former NCR Chairman Robert Oelman and Vic Cassano, founder of the Cassano pizza chain.

Overcoming challenges

In 1938, Brown became the first Dayton resident to use a seeing eye dog.

Before she could receive the dog, she also had to be trained.

In preparation, she went to dancing school in the winter and was walking with several friends to get herself into physical condition for the training. It was necessary for Brown to be able to walk three and a half miles per hour.

Brown then traveled to Morristown, New Jersey in June 1938, to take the training course required before a dog could be released to her.

Brown’s seeing eye guide dogs, of which she had three, were almost as well known as she was. Gillie, being the last, was at her side during her final hospital stay.

She also had Miss Effie until 1960, and before that, Topsy until 1948. Each served Brown about 12 years.

An author

After working on her autobiography for 15 years. “Corridors of light,” was published in 1958.

She also wrote a book of poetry. “Into the Light,” was published in 1946. It was later made into a talking book for the blind.

At the time of her death, she was planning a book on seeing eye dogs.

In “Corridors of Light,” Brown explained what happened when she got her degree at Ohio State: “The placement agent told me, ‘We think you might secure a job as an instructor of basketry or weaving in a school for the blind.’ I was hurt, furious. I came to college to use my mind, not my hands.”

A full life

Brown lived at the Dayton Biltmore hotel for many years.

She was a founder and former president of the Montgomery County Association for the Blind.

In 1960, Brown was unanimously named “Outstanding Woman of the Year” by the Dayton Federation of Women’s Clubs.

She died July 21, 1964 at the age of 76, at Kettering Memorial Hospital.

The words on her headstone at Memorial Park Cemetery included a verse she wrote, which reads, “I could not see the daisy I had found, Yet I was glad I did not need to see it; I traced its petals with my fingertips, And so through touch I made it part of me.

When asked how she made her dreams come true, she said, “I have my own formula. Be true to yourself. Cultivate the best in life — books, friends, ideals. Make use of what you have — don’t waste, don’t ignore. But chiefly: think, work and pray. Are not these things available to all of us?”

About the Author