The Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction currently has 12,272 employees, according to the department. The number includes 6,655 corrections officers, 491 parole officers — and some 2,000 medical workers — who go home every day to their families.

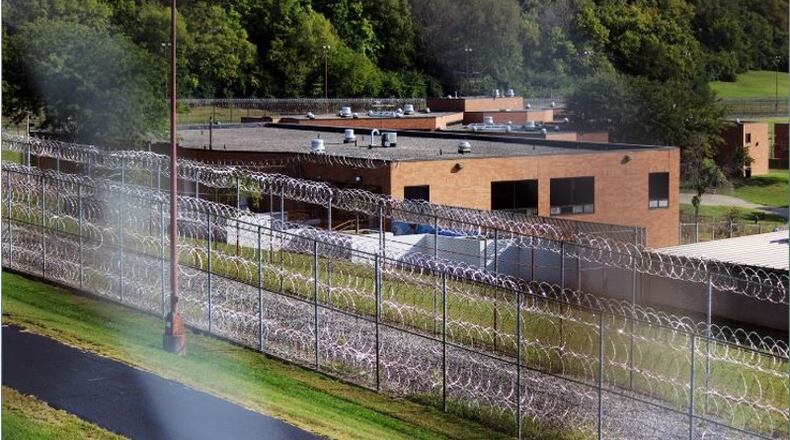

Because of the close-quarters of inmates and the huge workforce that comes and goes daily, outbreaks of COVID-19 in prisons have the potential to spread quickly throughout the populations there and move beyond the walls.

The union that represents prison staff has called for the Ohio National Guard to assist.

“Our members and their families suffer due to the negligence that still exists,” Ohio Civil Service Employees Association President Chris Mabe said in an e-mail to the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction director.

John Dawson, 55, a corrections officer at the Marion Correctional Institution, died of the disease April 8.

Springfield native Charles Viney Jr. was the first Ohio inmate to die of COVID-19. His death was announced Monday by DeWine. By the end of the week, more inmates had died — all at the Pickaway Correctional Institution.

By Friday, 692 inmates and 197 staff had tested positive and 32,018 — 65% — of inmates in Ohio-run prisons were in quarantine as coronavirus radiated through cell blocks, pods and dorms.

Dayton Correctional, a women’s prison, reported its first COVID-19-positive inmate last week.

“We’re all trapped,” Abigail Eberhardt, an inmate at Dayton Correctional Institution told her grandmother Mendy West.

“She said, ‘Grandma, I know I did wrong. I know I’m an addict. I know I keep getting in trouble. But I didn’t sign up for a death sentence,’” West said.

MORE: Coronavirus: First Ohio inmate to die grew up in area

While coronavirus cases are expected to increase inside state prisons, the problem will not spiral out of control, Ohio DRC Director Annette Chambers-Smith said.

• Put more than 32,000 inmates at 21 prisons, including those at Dayton Correctional, Lebanon Correctional and Warren Correctional, into quarantine, which restricts their movements and activities.

• Conducted temperature checks on staff and vendors before they enter any prison.

• Halted visits to all 49,000 inmates as of March 9 but added free phone calls and video visits.

• Switched to two meals a day from three.

• Ordered testing for all inmates in prisons with confirmed coronavirus outbreaks.

• Permitted inmates to wear cloth masks.

Coronavirus: Confused about unemployment? We answer your questions.

But there is little opportunity for social distancing inside prisons, where inmates often sleep together in cells or in some cases large, open rooms with bunk beds just a few feet apart, like where Viney was housed with other inmates at Pickaway Correctional Institution.

Although Viney had been in poor health, his living conditions likely contributed to contracting the virus, said his sister Kim Salah of Dayton.

“He was in a dorm setting,” Salah said. “So there are germs all around anyway. Every time somebody would get a cold it would be serious for him because of the condition he was in.”

Salah said her brother had been sick for about a year and on oxygen for a collapsed lung.

Viney was serving time for murder in Clark County and felonious assault and robbery convictions in Ross County. His expected release date was January 2021.

‘Drop in the bucket’

Ohio’s prison system is designed to hold about 35,000 inmates but currently holds 49,000. Overcrowding is a way of life inside.

Criminal justice reform groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union of Ohio, Ohio Justice & Policy Center, Policy Matters Ohio, Justice Action Network and others, have urged DeWine to take more dramatic steps to release nonviolent prisoners, particularly those with health conditions that put them at high risk for complications from COVID-19.

“What we have here in Ohio is no less than a human rights crisis unfolding before our very eyes,” said Gary Daniels of the ACLU of Ohio. “Mass incarceration is 100% incompatible with COVID-19.”

DETAILS: Stimulus payment problems in region: too much, too little, few answers

Daniels said the release of 10,000 inmates should be a starting point — which would bring the state prisons near what they were built to hold. Similar concerns extend to county jails, immigration detention centers, youth facilities and halfway houses, he said.

DeWine, a former Greene County prosecutor and the state’s top law enforcement officer as attorney general before he was elected governor, said he takes responsibility for release decisions. DeWine commuted the sentences Friday for seven inmates.

RELATED: Coronavirus in nursing homes: 'We are going to see deaths.'

He has used a strict criteria for early release: no violent offenders, no one with serious misconduct reports, no repeat offenders, and must be near the end of his or her sentence or over 60 and have health issues.

“This process will continue. So we would expect to continue to release prisoners — this specific group of prisoners — those with 90 days or less,” said DeWine, a Republican. “When someone enters that 90 day period of time, we will look at that individual to see whether they qualify, and we intend to move forward with those releases.”

The restrictions allow for only a fraction of state inmates to be released.

“While all release recommendations are truly welcome, this is a drop in the bucket of what is needed to mitigate the potential spread of the coronavirus throughout our prison system,” said Jocelyn Rosnick, ACLU of Ohio’s policy director.

READ MORE: Cash flow key to post-crisis economic recovery

That organization along with the Ohio Justice & Policy Center filed a federal class action lawsuit seeking to free prisoners at the low-security Elkton Federal Correctional Institution in eastern Ohio. Six inmates have died there and the Ohio National Guard was sent there to help.

An HIV-positive inmate, Derek R. Lichtenwalter, at the state’s Belmont Correctional Institution asked the Ohio Supreme Court to release him temporarily over health concerns. The suit was dismissed Thursday.

In his concurrence, however, Justice Michael Donnelly, one of two Democrats on the bench, said all branches of state government need to find a way to protect prison staff and medically vulnerable inmates.

DETAILS: Honda closure creates painful ripple effect

“The whole of Ohio’s government needs to take serious, unprecedented steps to prevent the catastrophe of unmitigated spread of COVID-19 to the tens of thousands of prisoners in Ohio, as well as to the tens of thousands of people who are prison employees, along with those living in the households of prison employees,” Donnelly wrote. “It would take broad action to release an adequate number of prisoners to make a difference in the overall prison population and protect those who are medically fragile.”

Donnelly also said proper consideration must be given to each inmate’s detention history, health status, risk of re-offending, as well as victims’ rights and general public safety before releases could occur.”

‘We’re just flying blind’

Ohio is testing all inmates and staff at Franklin Medical Center, Marion Correctional and Pickaway Correctional and pulling in help from other state agencies, such as the Ohio State Highway Patrol. Troopers are helping with perimeter security so more guards can work inside, she said. Staff at about 20 other prisons will also be tested, as well as anyone slated for early release.

“That will inform us on how to move forward,” Chambers-Smith said.

People incarcerated have been put to work making masks, gowns and shields for use inside the prisons and outside, Chambers-Smith said.

Indigent inmates are issued two bars of soap a month for showering and hand washing. Hand sanitizer — long banned because of its alcohol content — is now allowed. Inmates working for Ohio Penal Industries have produced or procured 5,528 gallons of hand sanitizer and distributed 2,112 gallons to prisons so far.

Some corrections officers doubt the steps taken are enough to keep them safe.

“We’re just flying blind,” said one officer at Warren Correctional Institution, who did not want his name used for fear of losing his job.

Coronavirus: Reopening will take place over a period of time, DeWine says

Corrections officers are angry that the DeWine administration isn't paying an $8 per hour premium for the public health emergency, a provision in the Ohio Civil Service Employee Association contract. The union filed a grievance over the hazard pay issue. And many DRC workers are upset that they've been issued masks intended to be one-time use and told to keep using them until further notice.

Meals have been cut from three to two each day in an effort to improve social distancing but corrections officers said little else has changed within most prisons. Inmates are still permitted to play basketball during recreation time, sit together at meals and be together in day rooms, they said.

In quarantined prisons, inmates are kept to their cell block groups for recreation and meals in an attempt to limit the spread, Chambers-Smith said. Recreation options have been changed in quarantined prisons — 20 of 28 as of Friday — so that inmates don’t share equipment. For example, they’re doing calisthenics or walking.

Chambers-Smith on March 29 directed prison with dorm housing to implement “head to toe” sleeping to maximize social distancing.

The union grievance over the $8 hazard pay is out of her control, Chambers-Smith said, but she did use another area of state law to arrange for emergency pay premiums of between 5% and 10%, based on the emergency level designated at each prisons.

“We are trying to keep people informed about what’s going on. With 49,000 people, I’m not going to say that all of them are jumping for joy at any given moment,” she said. “But I have to tell you the people that live in the prisons in Ohio are doing a really good job of trying to be productive and helpful where they can and honestly, I have less incidences of problems right now than when we’re not in this state.”

Counties shed inmates

The area’s county jails have been able to reduce inmate populations faster because they house a higher percentage of non-violent offenders, many typically awaiting trial or booked in on petty crimes.

The Montgomery County sheriff released 300 non-violent inmates. The jail is no longer accepting out-of-county warrants and has requested jurisdictions bring in those arrested for misdemeanors only if other alternatives have been exhausted, according to the county.

READ MORE: Coronavirus slowing Dayton region housing market

The roughly 460 inmates that remain incarcerated are a risk to society, Montgomery County Sheriff Rob Streck said.

“The majority are violent felons and people who the judges, probation and parole believe should not be released,” he said.

Montgomery County had no staff or inmates test positive for COVID-19 as of Friday, according to the county. Two inmates who exhibited symptoms earlier were placed in pressurized cells until tests returned negative. The two remain symptom free, according to Christine Ton, a sheriff’s office spokeswoman.

The jail implemented about 35 changes, including cancelling visitation, doubling the disinfectant schedule and issuing inmates bars of soap.

But the jail is short of hand-held thermometers and masks, Ton said.

“If we begin to have any positive cases, the masks would be critical,” she said.

Greene County reduced its jail population in half, from about 300 inmates to about 140 last week.

“We want to reduce the opportunities for our employees to transmit to, or receive from somebody, the virus,” Greene County Sheriff Gene Fischer said.

One Greene County deputy, who was not in contact with inmates, was hospitalized after testing positive for COVID-19 and is recovering at home.

The inmate population at the Butler County Jail is also down, dropping from 1,033 inmates a month ago to about 752 last week, according to jail records.

One Butler County Jail inmate, a 35-year-old man, tested positive last week for the coronavirus and was moved to another facility along with his cell mate.

‘You don’t have a few days’

Sheressa White of Hamilton said Daniel Hubbard, her partner of more than 25 years and father to their 10-year-old daughter, should be released from the MonDay Community Correctional Institution in Dayton where he has just weeks remaining to serve.

“The stress of COVID-19 is horrible,” White said

David Harris has less than two weeks left at Grafton Correctional Institution on a Greene County burglary sentence, but that time will seem like an eternity, said his girlfriend Kristin Cotterman of Jamestown.

READ MORE: 1.25M Ohioans seek ballots in 1st mail-in only election

“He’s like in a big gymnasium with all these bunk beds that are not even three feet apart,” she said, “He’s so scared that he’s going to contract the virus and then by the time he gets to come home, he’s going to give it to me and everyone else.”

Because he had been in prison before, Harris isn’t eligible under DeWine’s early release plan.

“I get that there are legislators, there are processes — I understand completely. But what I don’t understand is how you can sit there on the outside looking into these prisons and say it’ll be all right, they’ll be OK for right now, we’ve got a few days,” Cotterman said. “No, you don’t have a few days, you don’t even have a few hours. This stuff is spreading so quickly.”