Working a 1-2 count, the fourth pitch from Wright State’s Luke Stofel — a 95 mph fastball that drifted inside — clipped the bill of Kucera’s black helmet and ricocheted, full force, hitting him in the mouth.

Chuck Gerl, an NKU parent who works as a paramedic, rushed out of the stands, and got down in the dirt to hold a towel to Colton’s mouth and try to stem the profuse bleeding.

“It was an extremely scary situation,” said Steve Dintaman, the NKU assistant coach who once led the Sinclair Community College baseball program, still lives in Englewood and had recruited Colton from an Arizona junior college to Northern Kentucky.

In that fearful, unsettled moment, Staci said Gerl looked up and saw “this man standing above him” who said “’I’m a dentist.’ “Chuck said it felt like there was this aura about the man…Like he was an angel out of nowhere.”

Dr. Greg Notestine played baseball at Wright State in the early 1970s and since then has become a semi-regular around the program, watching some games from the Raiders’ dugout as “the unofficial dentist” of WSU baseball, he said.

Running a little late that day, he’d slipped into the back of the dugout just after that May 7 game had begun and saw the commotion at home plate. When he heard someone say “hit in face,” he knew he had to help.

The impact had knocked out Colton’s left front tooth — root and all — and had pushed the other front tooth back into his mouth. There was a hole in his lip and likely microfractures in the bones that once held those teeth in place.

Notestine said they figured the Norse outfielder was suffering a concussion — it would be his third in three seasons of college baseball — when they asked him his name and he answered: “Purple.”

Colton now says remembers seeing the fateful pitch: “It was a two seamer and had a lot of movement, but I never thought it was close to hitting my head.”

He said his next memory also was of a winged figure, but not the one Gerl had sensed: “When I fell to the ground, I had my right arm below me to prop me up so I wasn’t just lying there. That’s when I looked at my left hand and saw about three left hands. It’s one of the most bizarre feelings I’ve ever had.

“I felt like when you watch Tweety Bird (the Looney Tunes character) and he gets hit by a hammer and suddenly you see a bunch of different Tweety Birds.”

After putting on gloves and checking to see the damage to Colton’s mouth, Notestine asked if anyone had found the missing tooth.

Eventually Norse head coach Dizzy Peyton discovered it in the dirt.

“He told me he almost threw up,” Colton now adds with a laugh.

Notestine stressed not touching the tooth too much and had it placed it in a jar filled with Save-A-Tooth preserving solution.

He said they needed to get to the hospital so Colton could have CT scans and suggested Miami Valley because it had a dental clinic.

When the ambulance pulled onto the field, Colton gave a thumbs up as he was lifted inside. Notestine and Norse assistant coach Hunter Losekamp got in with him.

Notestine’s comforting demeanor was the tonic he needed, Colton said:

“He kept me calm through the whole process. In the ambulance and in the emergency room, it was like I knew I was going to be OK.” He said he was further buoyed when he got a text from Stofel: “He wanted to make sure I was alright. He said he was praying for me. It was definitely very cool of him to do that.”

As all this was going on, Staci said she and her husband Ken got a phone call as they sat in their Sun City, Arizona, home waiting to watch the game on their computer.

“I saw the call was my son’s number,” Staci said. “I answered it ‘Hey Buddy, what’s up?’

“But it wasn’t Colton, it was his coach, Dizzy Peyton, and my husband now says I told him, “This isn’t going to be good.’

“He told me what happened, but I wasn’t hearing most of what he said, except the word concussion.”

She discovered there was just one flight later that day from Phoenix to Cincinnati. Although it was full, she put her name on the wait list, hurried to the airport and again through heavenly intervention, she says, one seat suddenly opened.

Back at Miami Valley, after Colton underwent his scans, Notestine said they were told the now privately-owned dental clinic was closed.

He called the woman to whom he’d sold his dental practice in Beavercreek — he now works out of the PedZ Dental office on Far Hills Ave. in Kettering — and she told him to go in and do whatever he needed.

He stitched Colton’s lip and then reset and bonded the teeth so they were fortified.

Although it’s recommended a dislodged tooth gets put back in within 20 minutes, Colton’s had been out close to 90 when Notestine instructed a dental intern at Miami Valley how to do it.

“My understanding is that if it weren’t for Greg, the kid would have lost a tooth or two,” said WSU athletics director Bob Grant.

“The word I use for all this is ‘miraculous,’” said Staci, who was surprised when she finally arrived at her son’s apartment. “Except for a swollen lip, he didn’t look that bad.”

She credited much of that to Notestine:

“I don’t understand how a man like that just happens to show up at this game — at the exact moment he was needed — and then steps on the field and takes charge. And afterward it wasn’t simply ‘Hey, good luck. Bye-bye. Gotta go.’ He stayed with our son for every step.

“But the more I’ve found out about him, the more I realize that’s how he is.

“What a wonderful, altruistic man.”

‘A good soul’

Notestine’s empathy for others, he said, was first developed by his parents, Genevieve and Delmar, as he grew up in East Dayton and then later, when he and his wife endured a tremendous loss of their own.

“As a kid, I remember times coming home and there’d be three extra kids at our dinner table,” he recalled. “My mom would say, ‘Yeah, they’re going to spend the night.’

“It wasn’t until years later that I found out the kids’ dad was in jail and the mom had her own (serious) problems. For my parents, there was always a place in their hearts to do for others.”

Notestine went to Carroll High School and then Wright State, where he joined the Raiders baseball team for the 1971-72 season. But he’d developed arm trouble in high school and at WSU it worsened until he couldn’t throw and he said he only was used as a pinch runner.

He pursued his studies, became a dentist and married Karen Heider, who was also from Carroll.

Initially they had trouble having children and adopted a baby boy at birth they named Andrew. As they’d been searching for a child, Karen became pregnant and son Luke was born six months after they got Andrew.

“Having two little boys, gosh it was so much fun,” Notestine remembered quietly as we sat together in the Nischwitz Stadium the other morning.

But his smile evaporated and his voice wavered as he told about losing Andrew in June of 1983:

“He was 20 months old. We were at the swimming pool and he had been eating some bite-sized pretzels. He got up and ran and sucked them down and choked.

“They got his heart going, but the next day he passed away.”

As he and Karen dealt with the crushing loss, they were contacted about a little girl who was up for adoption. They learned she’d been conceived the week Andrew died and that helped them make their decision.

“I felt like: ‘God, you’re talking to us here,’” he said. “That’s how we got Bethany.”

“Having lived through that traumatic experience taught me the value of life,” Notestine said. “It made me a better parent, a better neighbor, a better co-worker, overall, just a better person. I learned how fragile life can be. I learned to appreciate every day. And I know (Andrew) is in the hands of God and that gives me peace of mind.

“And over the years Karen and I have talked to other couples who lost a child to let them know it isn’t the end of the world. We look at that as a gift we could share with others going through the experience.”

His embrace of life shows in his daily undertakings, Grant said:

“From the very first time I met him, I thought, “Wow, this is a genuinely kind, good-hearted guy. Within five minutes of meeting him, you realize he’s just a good soul. And I think the day that NKU player was hurt, he showed that again.”

It’s also been evident in the decades of volunteer work he’s done at The Good Neighbor House, said its executive director, Michelle Collier.

Located at 627 E. First St. in Dayton — www.goodneighborhouse.org — the nonprofit organization offers medical treatment, dental work and a food pantry to the under-served in the Miami Valley.

Notestine directs the dental clinic and now serves on the board of directors.

His dental work — just as in his private practice, which draws people from across the nation — now centers on aiding tongued-tied people, from infants to adults, so they are able to nurse, eat, speak and sleep better, as well as overcome the stigma that often comes with the condition.

“He is just an amazing man,” Collier said. “He gets the big picture. He knows it’s not about making money. It’s about serving others and making sure that people know there are things that can be fixed in life.”

Back in the batter’s box

In the weeks that followed the accident — as Colton went through concussion protocol and visited dental specialists closer to NKU for everything from root canals to his ongoing Invisalign regimen with clear plastic teeth aligners — he vowed he’d be back playing by the Horizon League Tournament, which began 2 ½ weeks after he was hurt.

He was driven, in part, by the sense of brotherhood he felt with the team he’d just joined that season after two years at Glendale Community College in Arizona.

He’d chosen NKU over Hawaii because of few factors, including the recruitment by Dintaman.

“He reached out to me after seeing me at a junior college all-star game,” Colton said. “The first time we talked over an hour. It felt like I was talking to one of my good friends.”

“What a man!” Staci said. “The things he said about the program have all been true. It’s been a great place for Colton.”

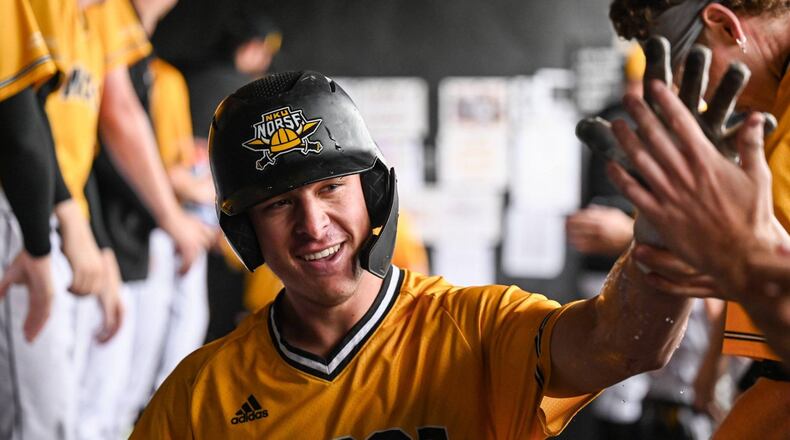

And sure enough, on May 24, there was Colton, at bat for the Norse in their Horizon League Tournament opener, right back at Nischwitz Stadium.

He’d been medically cleared the day before but only if he wore a helmet with a wire cage across the front. It was the first time he’d face live pitching since he’d been hurt.

Staci and Ken were in the crowd and she said she was “scared to death.”

Colton said while it “definitely was a strange feeling” being back at WSU, he pushed away any fears:

“I’ve had thousands of at-bats in my life, so once I stepped in the batter’s box, I never thought about getting hit in the head again.”

He got one hit that day against Purdue Fort Wayne and then smacked two doubles the next day against Oakland. On the third day — NKU’s final game — he added two more hits.

He was named to the All-Tournament team and finished the season as the Horizon League’s batting champ with a .382 average.

Before the tournament began, Staci and Ken surprised Notestine and visited him at his Far Hills office. Then after the first game, Colton met him on the field.

Notestine said he’s been impressed by Colton from the start:

“I never met a nicer kid in a stressful situation. He was polite, courteous, calm. He was as true gentleman.”

Colton is now back at Northern Kentucky, training daily while getting more work done on his teeth — they’ll be as good as before Notestine believes — and he’s working for the Cincinnati Reds.

Just as he liked what he saw in Colton, Notestine has developed a real appreciation of the NKU team.

He told how, after he’d finished taking care of Colton the day of the accident, the Norse team bus pulled up to Fairfield Road dental clinic where they were:

“Every team member got off the bus and they were cheering. They were just one step away from hoisting Colton on their shoulders.

“Their attitude was phenomenal. I remember thinking, ‘This is the Horizon League at its best. These are kids who still want to play. You can see they love each other.’

“Man, that just warmed my heart.”

Colton felt it, too:

“I couldn’t believe it when the bus pulled up. They’d waited for me!

“I probably gave out 40 hugs right outside the bus.”

And although his lip was swollen, he managed to give enough of a smile that you saw his teeth.

Thanks to an angel, you saw all of them.

About the Author