A couple of hours before we talked, she had had a light workout in an outdoor ring set up in the middle of Fourth Street in downtown Louisville. The moment she slipped through the ropes, the large crowd that had gathered began to serenade her with a chant from the past.

“Ali bomaye ! … Ali bomaye!”

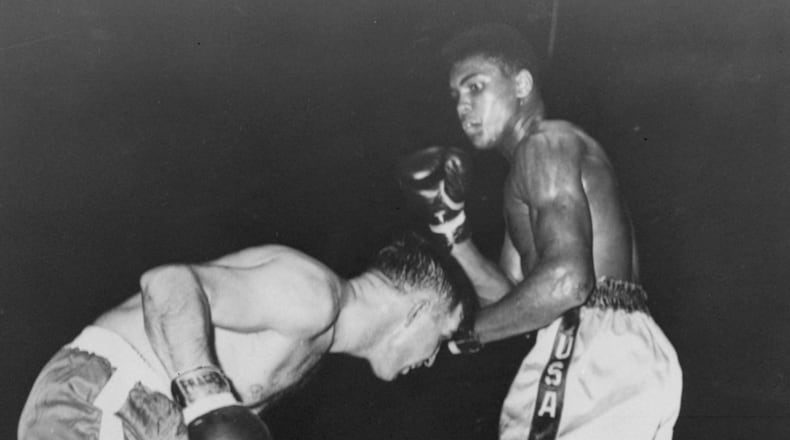

That’s the cry that echoed through the streets of Zaire in 1974 as her dad prepared to meet the seemingly indestructible George Foreman. Buoyed by the love and belief of the African people, Ali then dismantled Foreman in eight rounds.

“I didn’t know people here would be so proud to be from the same town Muhammad Ali is from,” Laila told me that July day in 2004. “They really have a special kind of love for me because they love my dad so much and what he stood for.”

She started to laugh: “I get Muhammad Ali stories everywhere I go, but especially here — women he dated here, they come up and say, ‘You know, your daddy really wanted to marry me.’ ”

- TOM ARCHDEACON: Ali's gift was elevating us all | VIDEO: Arch and his relationship with Muhammad Ali |

- CONTINUING COVERAGE: When Muhammad Ali saved 15 hostages in Iraq

- D.L. STEWART: Remembering a different Muhammad Ali

- Locals who knew The Champ: "He was a great friend."

And that brings me to my favorite Louisville story about Ali, who was known as Cassius Clay when he was growing up on Grand Avenue in the city’s West End and attended Central High School, the only black school in the then-segregated town.

Though not as well-known as many of the tales being told this week, it is pretty remarkable. It’s about the day “The Greatest” got stretched out cold after taking one on the kisser.

It was during their junior year at Central that Arethea Swint and Cassius began to date.

His teasing and braggadocious ways were a cover for his early shyness around girls and it took Cassius nearly a month until he had the courage to ask her for a goodnight smooch.

“On the night he did, it was late,” Arethea once recalled in a newspaper memoir. “It must have been around 12:30 or 1. We were being quiet because my mother had said there was no company after 12, and he didn’t have any business being up that late because he was in training.

“I was the first girl he had ever kissed and he didn’t know how, so I had to teach him. … When I did, he fainted. Really, he just did.

“He was always joking, so I thought he was playing, but he fell so hard. I ran upstairs to get a cold cloth.

“When you live in the projects, a lot of times mother would wash and lay the towels on the radiator to dry. So I looked for one and got some cold water on it and ran back down the stairs.”

She patted his face and when he finally came to, she asked, “Are you OK?”

“I’m fine,” he said, “but nobody will ever believe this.”

Gold lost, not tossed

Ali died at a Phoenix-area hospital where he had been treated for respiratory problems brought on by the Parkinson’s disease he’d battled for over 30 years.

He will be memorialized in two services in Louisville later this week

Thursday there will be an Islamic Prayer Service at the KFC Yum! Center.

Friday, following a procession through town, part of it going along Muhammad Ali Boulevard, there will be a communal celebration at the Yum! Center attended by the likes of King Abdullah II of Jordan and Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan and will include addresses by former president Bill Clinton, comedian Billy Crystal and broadcaster Bryant Gumbel.

Over the next few days you’ll hear plenty of Louisville stories about Ali.

Some are well known, like how, as a 12-year-old, his beloved Schwinn bike was stolen at a street fair. In tears, he told policeman Joe Martin, who happened to train amateur boxers, that if he could find the thief, he was gonna “whup” him.

Martin’s comeback — as Ali once recalled — launched a career: “Don’t you think you better learn to fight before you start fightin’?”

Other stories you’ll hear will not be true. Ali did not throw the Olympic gold medal he won in Rome into the Ohio River after he was denied service in a Louisville restaurant. He lost it.

Laila told me a story that involved her grandmother, Odessa Clay, who she remembered visiting as a child.

She said her grandmother told her how she was lying on the bed with her infant son and he innocently swung out his arm and caught her in the mouth. The punch loosened a tooth that she eventually lost.

As a young teen, Clay was effervescent, lovable, sometimes silly and always earnest, but he did have some quirky ways.

Although he ended up winning 131 of 138 amateur fights, two national Golden Gloves titles and two national AAU titles, he almost didn’t make the 1960 trip to Rome.

He was afraid to fly and was close to grounding his entire Olympic dream.

As Joe Martin’s son once explained to a Louisville reporter:

“My dad took him to Central Park and talked to him for hours. He finally agreed to fly, but then he went to an army surplus store and bought a parachute and actually wore it on the plane.

“It was a pretty rough flight, and he was down in the aisle, praying with his parachute on.”

Man of principle

Ali never needed that parachute … then or after.

He always managed to soar, even — if you look at it a certain way — when he was reviled by a segment of the population for converting to Islam, changing his name and then, on the moral convictions of his religion, refusing to join the military fight in Vietnam.

Much of the public eventually came around on him because he forever remained a man of principle. He spoke out for what he believed and took the repercussions that followed. In his case, he was stripped of the title and banned four years from boxing.

Such a stand is all but unheard of among today’s high-profile, endorsement-conscious athletes.

Long before Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, Ali ended up the most famous man on the planet. He was embraced because he always showed backbone, a big heart and an unflappable resilience.

And the latter brings me to the last of my favorite Louisville stories

Before the Rome Olympics, he would get up before dawn each day, put on his sweats and steel-toed work boots and run through the city streets.

As first light came, he’d race the school bus and come shadowboxing past the guys beginning to congregate on the street corners — especially those around a peanut vendor at 10th and Walnut — and he’d tell anyone who’d listen:

“I’m going to be the next heavyweight champ. I am the greatest.”

As Lawrence McKinley once told Sports Illustrated’s William Nack: “Cassius Clay used to come up the street acting like he was hitting people. Shadowboxing and throwing punches in his heavy shoes. Nobody ever dreamed he’d be world champ.”

One morning McKinley said one of the regulars, Gene Pearson, got tired of all the yapping and the next time Clay came past, he stepped out and “WHAM!” he hit him with a hard right to the kisser.

It was shades of Arethea Swint all over again — only with a different result.

“Clay liked to go all the way down,” McKinley said. “He went to his knees, just like he was gonna fall, and he stopped himself and looked up at Gene, and he stretched his eyes real wide and he came up and — whew! — he must have hit Gene 15 or 20 times, so fast you could hardly see the punches.

“Gene started saying, ‘Get him off me! Get him off me! Yeah, you’re gonna be the champ.’ And Cassius went right on running up the street. Never said nothin’.

“The next time Cassius came by, one of the guys said, ‘Are you gonna hit him again?’

“And Gene said, ‘Hey, champ!’ “

About the Author