“My parents sacrificed to send us to Catholic school, and they said, ‘If you’re going to go to college, you’ll have to pay for that on your own.’ They couldn’t afford it.

“I worked a lot of jobs coming up. I had a paper route when I was 10 years old, and I worked as a janitor at my grade school when I was in the seventh and eighth grade.”

When he was a high school senior, he worked as a janitor at UD Arena.

“My supervisor was Herb Dintaman; he was the Director of Facilities at the Arena,” Courtney said. “He was tough on us when we worked there, and he demanded a lot. In the summertime I remember being out in that blacktop parking lot picking weeds out of the cracks for days.”

Back then he had no idea who Dintaman really was or what he had done.

“To me he was kind of just this old rough, gruff guy,” Courtney said with a chuckle. “But he did seem to be fair and loyal to us.”

Courtney had applied to schools like Marquette, Dayton, and St. Johns, because his parents had met at the Queens college when they were students there.

Since he’d been a manager for Joe Petrocelli’s basketball teams at Alter, Courtney, on a bit of a whim, applied for the scholarship that used to be given to the lone manager on Don Donoher’s Flyers’ team in those days.

He said a lot of people sought that scholarship, but in looking at the applications, Donoher noticed Courtney worked for his friend Dintaman at the Arena.

Although Courtney wouldn’t find out until years later, Donoher had called Dintaman, who told him:

“Hire him! He’s a good kid.”

Donoher did just that and from 1981 to 1985 Courtney had the experience of a lifetime as the team’s student manager.

As a freshman he tended to a powerful UD team ― detoured by Kevin Conrad’s February bout with mononucleosis and a late-season loss at Canisius — that just missed the NCAA Tournament, but made a splash in the NIT, beating Connecticut at home and Illinois at Assembly Hall, before losing at Oklahoma.

Two seasons later he was part of the Roosevelt Chapman-led Flyers who made a run to the Elite Eight.

Senior year he aided the UD team that made another NCAA Tournament and lost by two points — in a first-round game at UD Arena — to Villanova, the eventual national champions.

Along the way he met prominent opposing figures he really liked — guys like DePaul’s legendary coach Ray Meyer and Oklahoma All-American Wayman Tisdale — and he was there for big regular-season victories over rivals Notre Dame and Marquette and nationally-ranked teams like Maryland and DePaul.

Courtney went on to get a grad assistantship at UD, got his master’s degree and then fashioned a three-decade career in software IT sales. He and his wife Jennifer have two daughters in college, Catherine and Reagan.

Over the years, he tried his hand at stand-up comedy, donated a kidney to his brother, and wrote a children’s book about Rudy Flyer that included Don Donoher in the tale.

He said he happened to be back at UD about 15 years ago and was dismayed to find out the basketball managers — today the team is tended to by several — no longer are on scholarship. They’re all volunteers.

Accompanied by former Flyer Rory Dahlinghaus, he said he visited with Donoher and talked about that:

“He told me how Tom Blackburn had told him that the Marianist priests and brothers who ran the university back then wanted to make sure there was fairness and justice in all things, and they felt managers should get scholarships, too.

“I don’t know if it was Father Roesch (the UD president at the time) or who, but Blackburn and Donoher were told they got 12 scholarships for varsity, 12 for freshmen when there was a freshman team, and one scholarship was for the manager.

“Donoher honored that, like Blackburn had, but the practice stopped in the Jim O’Brien era.”

As they talked, Donoher told him he’d gotten his scholarship thanks to Dintaman, who had gone to bat for him.

“I hadn’t known that,” Courtney said.

He said he never realized the weight Herb Dintaman carried, nor the softness and goodness he had under that gruff exterior:

“I do know if I hadn’t gotten that scholarship I might not have gone to college or, at least, I wouldn’t have gone to UD.”

After leaving Donoher, Courtney decided to do what he could to bring back the Marianist way as far as UD managers were concerned.

He wanted to get a scholarship for them again and, in the process, he hoped to honor Herb Dintaman.

Once he knew Dintaman’s whole story — from his heroism in World War II to his many achievements at Dayton, as well as the way he once was scapegoated at the school and yet how he forever remained loyal and committed to all things Flyers — he realized he was someone that never should be forgotten at UD.

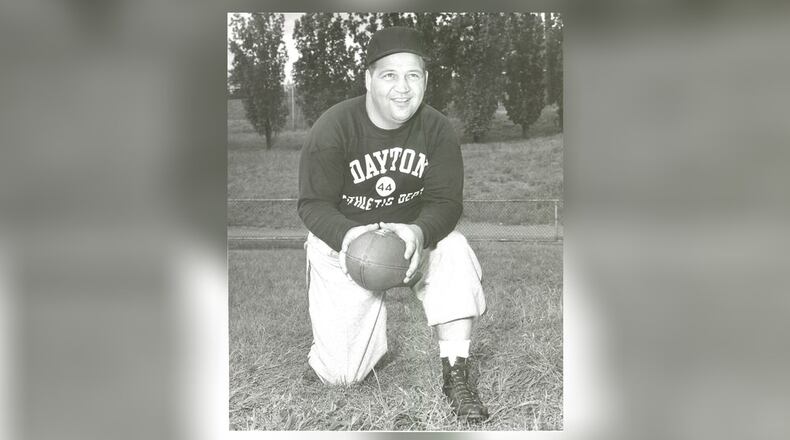

A coach at UD

Dintaman, who grew up in Tamaqua, Pennsylvania, knew hardship from an early age.

His mother died when he was a youngster. As a kid he earned 50 cents a day doing back-breaking work as he followed a plow and pulled potatoes from the dirt.

After standing out as a football player at Hazelton High School, he got a scholarship to St. Bonaventure. But his collegiate career was interrupted by World War II, and he served in China, Burma, and India.

While he was in China, Japanese aircraft strafed the airfield he was at, and two US fliers were trapped in their burning plane until Dintaman ran out and pulled them to safety.

The effort won him the Bronze Star.

Back at St. Bonaventure he became captain of the 1947 football team, then began coaching at his alma mater before being recalled to service, and sent to Germany.

After returning stateside, he coached at New York University and in 1954 joined new UD coach Hugh Devore, the Notre Dame product who had coached the Green Bay Packers the previous season.

“When we first came to UD we lived in the Army barracks on campus,” said Margaret Gantt, Dintaman’s oldest daughter, who eventually would enroll at UD in the fall of 1968, then opt out for a career as an American Airlines attendant before returning for a long career in UD Arena ticket office.

“In those early days they had army barracks in the parking lot by St. Mary’s Hall,” Gantt said. “A lot of professors lived there — like Sandy King and Erving Beauregard.

“The place was the pits, but they made it like a family atmosphere. It didn’t matter where you worked on campus, you were part of the family. At night they’d go out and turn the car lights on and play croquet and stuff.”

Dintaman was hired by Blackburn to coach the freshman basketball team. Later he coached baseball, as well.

He guided what was one of the greatest collections of UD basketball players ever — the 1960-61 freshman team — that featured Roger Brown, Bill Chmielewski, Chuck Izor, Gordy Hatton and Jim Powers and made it to the National AAU semifinals as it amassed a 36-4-1 record.

‘He loved UD’

When Brown was unfairly targeted in an NCAA gambling probe — he was never charged with any infraction and wasn’t found to have any connection to gambler activities during his UD days — the Flyers star was exiled from the university and all of college basketball.

Dintaman was especially upset by the treatment of Brown and talked about it later in his life:

“Roger was robbed. Nothing was ever proven on him. The decision at the school came down fast and from higher up than I knew. Roger was a good person who got a bad deal.”

So did Dintaman. When the NCAA focused on another issue at UD, the school — in an effort to buy favor with the sanctioning body — unfairly singled out Dintaman for not monitoring the Roger Brown situation.

“Herb took the fall for the Roger Brown situation and that was an absolute tragedy for both Roger Brown and Herb Dintaman,” Courtney said. “Herb got demoted and that was wrong.”

When Blackburn hired a top assistant, he took Don Donoher over Dintaman.

“During my visit that time with Coach Donoher, he told me how Herb had every reason to hate him because he’d taken his spot,” Courtney said. “But he said Herb was his best friend all those years at UD and he helped him a lot.

“Herb remained loyal to UD until the day he died.”

“That’s just the way my dad was,” Gantt said. “One of his best friends was Don Donoher.

“You could step on him countless times and it wouldn’t matter — he loved UD. He cared about the school and would do whatever he could for it.”

After his coaching positions ended at UD, Dintaman became the school’s Director of Intramurals from 1963 to 1971.

After that, until he retired in 1990, he was UD’s Director of Athletic Facilities and oversaw the UD Fieldhouse, Baujan Field and the baseball field.

“My dad would take us over to Baujan Field after football games and he’d say, ‘We can’t pay people to clean up, so you you guys go under the stands and clean everything up. And any change you find, you can keep,’” Gantt said with a laugh.

“All we ever found were pennies or maybe some nickels.”

Dintaman also supervised maintenance and planned events at UD Arena.

In reference to the Arena, Donoher spoke to Dayton Daily News writer Bucky Albers about Dintaman when he retired:

“Stop and think what he put into this building. He was a slave to it. He typifies why the place is what it is.

“We’d come over for a Sunday evening practice and the floor would be so slick (following another event) that we couldn’t practice. I’d call Herbie and he’d be over in 15 minutes and wet mop it. That happened time after time.”

Gantt said her dad never shied away from the more challenging tasks:

“He’d never ask any of the kids to do something he wouldn’t do himself.

“He’d go to the top of the rafters and put a bucket up there for a leak or he’d plow snow from the parking lot.

“He did whatever it took because he loved UD so much.”

Seven years after he retired — in 1997 — Herb Dintaman was inducted into the UD Athletics Hall of Fame.

He died in 2002 — at age 82 — and is buried in Section 229 at Calvary Cemetery.

In the two decades since his passing — especially with a new generation of UD coaches, players, students, and fans — Dintaman and his story are mostly unknown around the school.

Courtney wants to change that.

‘I think he’d love it’

After he decided to launch a scholarship fund that could aid basketball managers and remember Dintaman, Courtney said it took a long time to make it financially viable:

“I’m not a personally wealthy person, so I worked quietly and anonymously and little by little I put money in and then I got a few other guys to kick money in, too.

“But we still didn’t have a lot — not enough to create an endowment — so it kind of stalled.”

Eventually he sent out a plea, via social media, to many in the Donoher basketball fraternity and got enough funds to start the scholarship on modest terms.

The first two recipients of the Herb Dintaman Endowed Scholarship for managers will be announced Wednesday when the Flyers team from this past season meets at an entertainment center in West Chester for its end-of-the-year dinner and awards presentation followed by some fun.

Courtney will be there and share some thoughts on Dintaman with the team.

Anyone wishing to donate to the Dintaman scholarship fund can contact the UD Office of Advancement at 937-229-2912 or Rory Dahlinghaus, Director of Development for UD, at 937-229-3089.

Courtney is proud that they’ve been able to revive a Marianist tradition and will give a pair of managers — chosen by the Flyers coaches — some financial assistance.

Just as importantly it will bring Herb Dintaman and his unwavering love for UD to the fore once again.

“My dad didn’t like attention, but I think underneath he’d be so honored by this,” Gantt said.

“I think he’d love it.”

The “rough, gruff” exterior would give way to his big heart and loyal embrace.

Once again — all these years later — he would be helping UD students.

About the Author