The US/Dayton/Wright-Patterson Air Force Base were essential components to get the Accords signed, and the US may have to get re-involved. Yet, I see it as the people of Bosnia (and the other ex-Yugoslavia Republics) that needs to step up, along with the European Union (which now includes multiple Slavic states) and make things happen.

- Laurel A. Mayer, PhD, Sinclair Community College

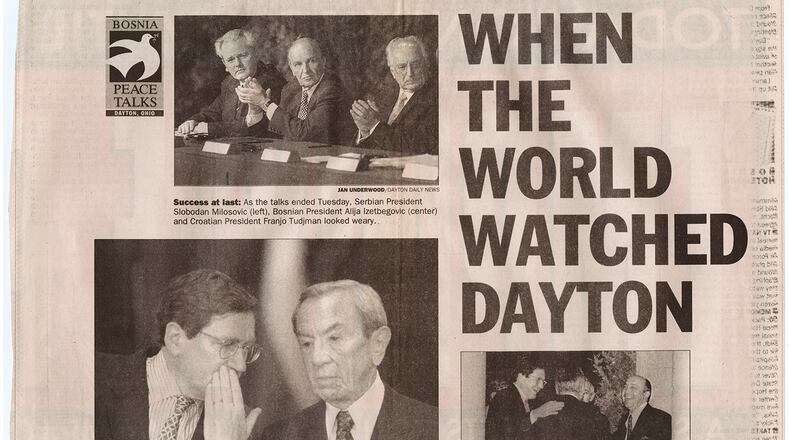

On Nov. 20, Professor Christian Raffensperger of Wittenberg University asked “Why… did the United States help to divide Bosnia based on ethnicity and religion?” He was referring to the settlement of the Bosnian war at a 1995 conference known as “Dayton.”

He said, “Though I have since read multiple books on the subject and talked with experts, I still do not have an answer.”

The answer is that there was no other way. There was a war on. It was entirely about which religious groups would have which pieces of land and which sources of power. The negotiations were about ending the war. The negotiations were – unavoidably – between the warring factions, the people with the guns. To get people to put down their guns required giving them what they were fighting for: territory and power.

Professor Raffensperger would apparently have preferred something more Madisonian, something like the U.S. Constitution, with its rules that are not so much about who would get power, but about how power would be achieved and distributed (checks and balances). That would have been the preference, too, of American Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, the creator and guider of the Bosnia talks. It would have been the preference of all Americans involved. But, unlike the framers of the Constitution, Holbrooke wasn’t dealing with representatives of states at peace. He was dealing with the people with the guns. They weren’t going to give up the power they had. The best that could be hoped was that they would give up their aspirations for more. Getting them to do that was a historic accomplishment.

Nobody had to tell Holbrooke or anybody else that the “Dayton” framework was not a permanent solution. Holbrooke told the Dayton Daily News that, for example, the idea of a three-man presidency for Bosnia – a Muslim, a Serb and a Croat – was simply awful and necessarily temporary. He and others thought the task of building a stable, genuinely democratic Bosnia lay ahead and would be difficult. But in war it would have been impossible.

For Professor Raffensperger to ask, in the context of Bosnia, “why do we encourage division by race and creed in other countries,” is grotesque, a turning of history on its head. The United States was – eventually, belatedly – the indispensable forces against such division. What we encouraged was peace and democracy.

As an employee of this newspaper, I visited Bosnia in 1997 with about 20 other Daytonians; we were the second such group to go. At that point, the word “Dayton” was magic in Bosnia, and attitudes about it were not complex. “Dayton” had simply brought peace.

But, of course, hindrances to lasting peace were clearly visible – in a form perhaps more understandable to Americans of 2021 than 1997.

“Dayton” envisioned elections. Quickly, however, it became clear that people in Bosnia were voting along ethno-religious lines; that is, they voted for a Muslim party, a Croat party or a Serb party. One American instinct was to say, “No, no, no. That’s not how to vote. Voting is supposed to be about philosophies of government, about ideology. Left versus right, and all that.”

Now, however, perhaps we can understand the Bosnians better, as tribalism and hatred of others threaten to take over American politics. And, as our own efforts to handle our diversity look lamer all the time, we can certainly understand the difficulties Bosnia faces, as outlined in the pieces accompanying the Raffensberger piece. I’m not sure we have the answers. I know I don’t.

I can offer one piece of small comfort: President Joe Biden is highly attuned to the Bosnia situation. He was deeply involved there in the days of “Dayton.” He knew the players and they knew him. He was once chosen as the keynote speaker at a post-“Dayton” conference on Bosnia in Dayton.

But his options are limited, especially in this time, when Americans are particularly suspicious of international involvement in internal disputes elsewhere.

In pursuing his options, he must – and does – recognize that problem in the Balkans is not “Dayton” and not the United States. It’s the Balkans.

- Martin Gottlieb, Dayton

About the Author