Tapping into these old story forms is no accident. By associating themselves with familiar formulas, usually found in fiction, presidential candidates can conceal any number of contradictions — e.g., former governors demonizing government, or former lobbyists trashing lobbying. The mainstream news media — as they do in all elections — play their role in the larger political narrative, overemphasizing polls and reducing elections to two-dimensional tales of “who’s winning/who’s losing.” Obscuring complex issues like immigration, climate change and wealth disparity, horse race narratives are simple stories, enhanced by the proliferation of polls and websites that track polls daily (realclearpolitics.com) and critique polling data (fivethirtyeight.com).

Back in 2008, Clark Hoyt, then public editor of the New York Times, reported that, of the 270 political articles published in the Times during the last few months of the election, “just a little over 10 percent were primarily about policy substance.” Hoyt noted that similar studies at the time also found that among other major news outlets “the vast majority of election stories were about the horse race, political tactics, polls, and the like.”

Today, not much has changed, as Thomas Patterson, Harvard’s Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press, noted this summer. “Too many polls, too much horse race,” Patterson stated at a recent conference. “That problem has only worsened as polling has expanded. Was the measure of Trump’s indictments truly whether they were hurting him in the polls? Are we to judge Harris truly by whether she surges or slips in the polls? Fitness for public office has long been underplayed, as have the issues of the campaign. Issues are not tissues, for disposal at campaign’s end.”

Political pundits like to argue that in politics the winners are those who tell the best story. Many Americans will make final judgments about who they will vote for based on 30-second TV or radio stories that air on local stations, cable channels, national networks and the internet. But note the lack of narrative imagination in this process. Like many 30-second product spots, political ads like the 1976 Carter spot are often romantic tales that associate a candidate (now a product) with wholesome virtues like honesty, patriotism and “family values.”

Candidates today are riding old tractors, wielding hunting rifles, and romancing adoring crowds. But in the end, we don’t learn much about the characters who gave the money for the ad, what their agendas are, and what the candidate’s obligations for financial favors might be.

Another genre, the over-the-top attack ad, also lacks imagination. You’ve seen the spots that scream, “HERE’S WHAT CANDIDATE X DOES NOT WANT YOU TO KNOW ABOUT HIS PAST!” These ads might claim — without evidence — that Candidate A has freed murderers from prison … or supported immigrants who eat their neighbors’ pets. The solution is simple: Vote for Candidate B. Unfortunately, though, we don’t get much information on the candidate’s ideas about how they are going to get a deeply divided and dysfunctional Congress to enact their proposed fixes for crime and immigration.

Local TV stations clean up in election years, especially those in swing states where political ads are lucrative and everywhere. In some cases, these stations quadruple the annual revenue produced in off-election years. Ad costs get jacked up so high that many local advertisers can’t afford to compete for air time. But this substantial ad revenue will dry up over time. As people “cut the cord,” breaking away from cable and broadcast TV, more and more ads will stream to social media and YouTube (with its 2.5 billion users), where advertising is cheaper and can better target audiences.

One hopeful sign: Young voters do not watch much local television. They’ve grown up in an age when fictional narratives have become more complex and sophisticated as dozens of streaming services vie for eyes. Asking young voters to believe 60-second romantic tales about candidates who can save us or dystopian fables about doomsday scenarios (if we choose unwisely) is a stretch.

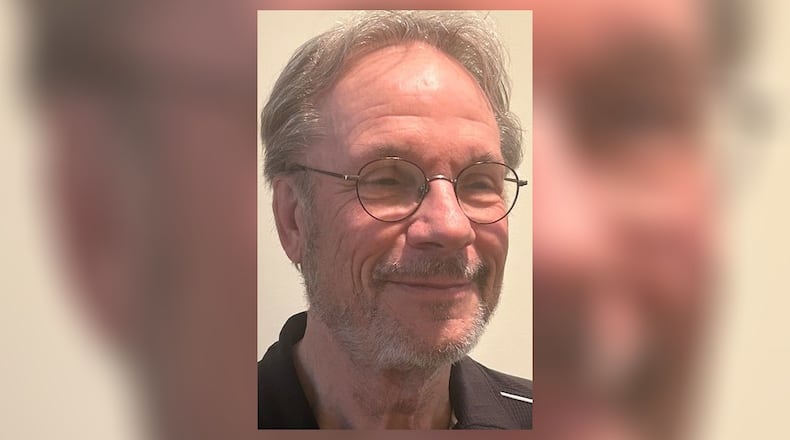

Richard Campbell is professor emeritus of Media, Journalism & Film at Miami University and co-founder of the Oxford Free Press, where this column first appeared.

About the Author