As the U.S. military and its allies assembled in the Middle East in the summer and fall of 1990 – Operation Desert Shield – in response to Iraq President Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, then-Col. Carlton set up the 1,200-bed Air Force 1702nd Contingency Hospital in combination with an Army Combat Support Hospital outside of Muscat, Oman. Yet, as Operation Desert Shield turned to Operation Desert Storm on Jan. 19, 1991, the hospital only took in 42 patients, and those were only from surrounding bases.

“We did not get any war wounded,” said Carlton, who offered beds to the Central Command surgeon to better utilize the facility.

To make the case for his hospital, Carlton traveled to the battlefield to offer assistance.

“I picked up a couple of Air-EVAC missions just to let more people know we existed,” he said. “I told Army commanders to send anyone to us.”

But it soon became apparent the Air Force could not meet the Army’s needs.

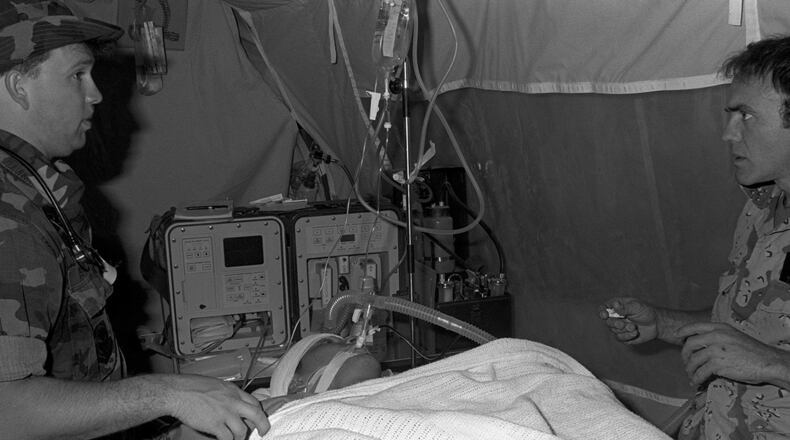

“We could not take people with catheters or tubes, much less needing a ventilator,” Carlton said.

Instead of relying on the Air Force, the Army built large hospitals closer to the front.

“The Army built up just like they did in Vietnam,” Carlton said. “They had a very big footprint.”

AFMS leadership wanted smaller hospitals connecting back to the United States, but to do that, they needed a modern transportation system. Although Carlton and other colleagues had been working on improvements to patient transportation since 1983, air evacuations were still very restrictive. The equipment needed to keep a patient alive was new and untested.

“Modern ventilators blew out lungs all the time,” Carlton explained. “We needed to work the kinks out, and we needed the opportunity to work in the modern battlefield. We needed critical care in the air.”

When the war ended in late February, Carlton and other AFMS officers returned home and brought their CCATT ideas to the Air Training Command.

“The war was not an aberration,” Carlton said. “We had to modernize our theater plans to be able to transport patients.”

Carlton and his colleagues trained three-person crews to work with new and improved ventilation equipment aboard airplanes.

“That was the long pole in the tent,” he explained. “When you take a critical care patient you say, ‘We can ventilate that patient,’ and you better be able to.”

With the new program up and running, the AFMS made CCATT available to the other services.

CCATT gained momentum in 1993 when Carlton and his colleagues traveled to Mogadishu, Somalia, for an after-action brief on the U.S. Army’s “Blackhawk Down” engagement and explained CCATT to the Joint Special Operations Command surgeon. He, in turn, handed Carlton a check and said, “I want that as soon as you can make it.”

The turning point came in 1995 during the Bosnian War, when an American Soldier riding a train to Bosnia was electrocuted by an overhead wire and fell off the train. He was immediately transported to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center, Germany, where doctors wanted him transferred to the burn unit at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas. When Maj. (Dr.) Bill Beninati picked up the patient for the flight to the United States, he was still very unstable. Somewhere over Greenland, the patient went into septic shock and Beniniati and his team resuscitated him. When they touched down in San Antonio, some 12 hours later, the patient was in better shape than when he left.

“That’s when the Army took notice,” Carlton said. “We had convinced them that we could do what we said.”

Soon, the Air Force Surgeon General at the time, Lt. Gen. Alexander Sloan, approved the CCATT concept. Later, with the strong endorsement of Air Force Surgeon General Lt. Gen. Charles Roadman II, CCATT became a formal program.

CCATT proved invaluable in the next conflict, Operation Iraqi Freedom, where casualty evacuation became a vital necessity, as well as in Afghanistan. Carlton is proud of CCATT.

“We have developed a modern transportation system to go along with the modern battlefield for the Army, Navy, and the Marines,” Carlton said.

Today, CCATT is considered a vital component of AFMS, but it took a war to liberate Kuwait some 25 years ago for the military to realize how badly it was needed.

About the Author