Credit: DaytonDailyNews

The Dayton Daily News last week obtained law enforcement records showing police were at Takoda’s home more than 10 times since his father brought him here, including during the period of time his father is now accused of abusing him.

Records show a February 2016 call from Montgomery County Children Services about Takoda’s then-9-year-old brother. “(Children Services) received a call that he has a black eye and possible child neglect/father refused for school or Children Services to see the child,” a Montgomery County dispatch log says.

A Dayton police officer found no one home and wrote: “No ans (sic) at door. Spoke w (Children Services) worker who advised that when home, father evasive and will never allow workers to enter home to check conditions. Suggested having school call to investigate issue further on alleged/possible abuse.”

Less than a month later, Dayton police visited the same home on a complaint that the boys’ father Al McLean was drunk and refusing to leave. The caller was Amanda Hinze, McLean’s girlfriend who is also criminally charged in connection to alleged abuse. She called again in May 2016 saying McLean hit her, records show.

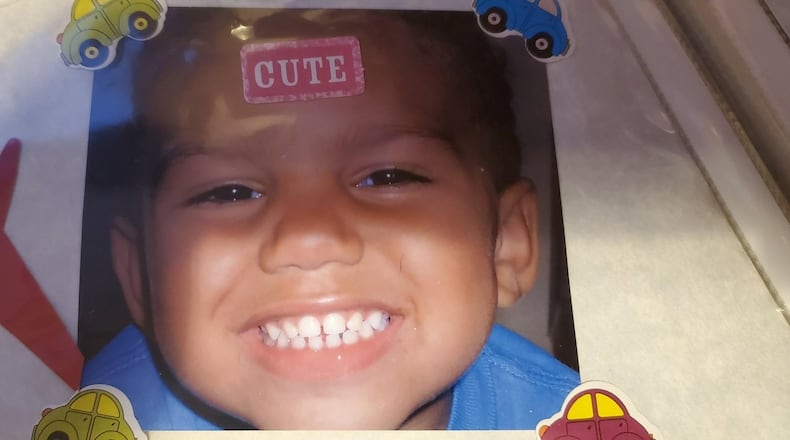

Timeline: The tragic life and death of Takoda Collins

Dayton police didn’t have full knowledge of the allegations of abuse at the home, the Dayton Daily News found. Databases used by officers in the field wouldn’t have told them that Dayton Public Schools employees were repeatedly calling Montgomery County with concerns that Takoda was being abused or neglected.

Meanwhile Montgomery County Children Services asked for police assistance twice, once for Takoda and once for his brother. Both times officers went to the house and found no one home.

Seven months before Takoda died, his mother called police to say she suspected he was being abused. Officers did not refer the incident to Children Services, records show. This occurred last year months after Ohio law changed and mandated that police officers report abuse if they suspect it.

Whatever action Children Services did take, they did not appear to involve the courts. Montgomery County Children Services officials say there wasn’t an open case on Takoda when he died. Montgomery County Juvenile Court officials say there is no record of a court case involving Takoda or his brother - a move that would have been required if the county had attempted to remove from them from home or get the family placed under a court-sanctioned case plan.

DDN Investigates: County children services fail state standards as abuse claims rise

Dayton Police Chief Richard Biehl said in a statement to the Dayton Daily News that his staff is examining how police, Children Services and other agencies communicate abuse complaints to each other.

“While more information needs to be known about organizational communication across the multiple entities that may have a role in the welfare of children, there are undoubtedly possibilities for improved communication, coordination and response to claims of child neglect/abuse across the various organizations that touch the lives of children,” Biehl wrote.

Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley told WHIO-TV: “I don’t think Dayton Police obviously did everything they could in their purview, but now the question needs to be broader: what can (the) county and city do to connect, to really make sure that something like this never happens again?”

Red flags started in Wisconsin

In addition to lack of communication locally, Takoda’s death revealed communication problems across state lines.

Takoda was born in Wisconsin. Before his first birthday, his mother Robin Collins was charged with abusing him and later went to prison for violating her probation with drugs.

Three days after a Wisconsin court granted his father, Al McLean, permanent custody of Takoda, McLean was accused of beating his fiance Amanda Hinze bloody with a pipe. Hinze, while covered with bruises and blood, denied the incident and became combative with officers, police records say. Felony charges against McLean were dropped by the prosecutor.

McLean got permission from Wisconsin to take Takoda to Pennsylvania despite claims by his mother, Robin Collins, that the boy was being abused. McLean instead moved to Dayton with Hinze, records show, and courts threw out Collins’ attempts to compel McLean to bring the child back.

Robin Collins said in an interview she has many regrets and admits she didn’t do everything in her power to keep Takoda safe. She now thinks she should have committed a crime to do that.

“I feel like I could have brought him back home and he would still be alive,” she said. “I also had the option of kidnapping him and I really regret not doing so. I feel like I could have come down here and took him. And he’d tell me ‘Mom he’s doing these things to me’ and we could go to the police station and I’d be like no we’re not going back there.”

Wisconsin officials won’t comment on how the case was handled there, citing confidentiality laws. Gina Paige, spokeswoman for the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families, said there are ways a child welfare agency in one state can communicate case information to another state, but the state would need to know to request that information. There is no national child welfare database.

Mom convicted of abuse

Child support filings show Collins first became pregnant with her son Takoda in Cumberland County, North Carolina. Collins said in an interview it was an unplanned pregnancy. Collins said when she came up with Takoda’s name she wanted his initials to be THC, after the active ingredient in marijuana.

Eleven months after Takoda was born, Wisconsin court records show Madison police assisted with a child abuse investigation and spoke to Collins after seeing photographs of Takoda with large bruises on his backside.

“This is all my fault,” Collins told police, according to court records that say she claimed Takoda started crying and she couldn’t get him to stop.

“I couldn’t take it anymore. I was afraid I would hurt him. I didn’t want him anymore. I couldn’t be with him. I got frustrated. I couldn’t take it, I couldn’t. He wouldn’t stop crying. I hit him. I hurt him. I’m sorry,” records quote Collins as saying.

Collins was sentenced to probation, then went to prison when she violated that probation; she said she slipped up by doing drugs.

Collins told the Dayton Daily News she didn’t hit Takoda, but was charged after her boyfriend hit her while she was holding the baby.

Collins’ mother attempted to get custody of Takoda, she says, but Wisconsin officials determined she already had her hands full with other children in her family she was raising.

Dad accused of violence early on

As McLean sought permanent custody of Takoda, he also built a criminal record. In April 2012, he assaulted a man who he accused of finding his cell phone in a parking lot. Police records say McLean choked the man unconscious and punched him in the face. McLean pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct, as well as bail jumping, in the case.

After receiving temporary custody of Takoda, McLean gained full custody on Oct. 23, 2013.

During the custody process, Collins wrote to the judge pleading for McLean to not be allowed to move Takoda out of Wisconsin. She made multiple claims that she said were being investigated.

“My son’s father was accused of choking my son. Other things include being beat with a belt, allowed to drink,” she wrote. “Takoda’s clothes are small for him and during my visits he smells and states he doesn’t brush his teeth.”

“Even though I went to prison, I wrote Takoda 1 letter everyday. I made him things and video taped myself reading books. He also came to see me. I have tried to keep a bond with my son, even through our separation.”

Three days after McLean got custody of Takoda, police in Madison, Wisc., responded to the alleged assault on Hinze.

Records state a witness said McLean crashed into Hinze’s car, then hit her over the head with a pipe when she got out of the car, then dragged her by the hair, punching her in the face, before throwing her into his car and slamming her legs in the door. Prior to the assault, the witness said, Hinze mentioned wanting to break up with McLean.

Police responded and found Hinze sitting in a car covered in bruises and blood. She denied getting into an altercation with McLean and accused witnesses of lying.

Takoda taken to Dayton

In June 2014, McLean filed with Wisconsin courts his intent to move to Pennsylvania. Collins signed a notarized letter agreeing to the move, then wrote a hand-written letter days later saying she was bullied and pressured into signing the first letter.

The court granted McLean permission to move to Pennsylvania. Two months later in December 2014, Hinze purchased the house on Kensington Drive in Dayton. Takoda was enrolled in Horace Mann Elementary School.

Dayton Public Schools officials say they reported abuse and neglect concerns to Montgomery County Children Services beginning his first year there.

Dayton Public Schools Superintendent Elizabeth Lolli estimates the number of reports at 15. She will not provide any records of those reports, however, citing privacy laws. There are no records of school staff calling police to the school to investigate suspected abuse.

The first call to Dayton police involving McLean was the February 2016 report about Takoda’s brother. They would be called to that house nine more times that year, including twice from Hinze calling complaining about McLean; once when McLean and a neighbor fought; once for an assault report; and when deputies serve a civil protection order against McLean from a woman who says he assaulted her.

In August 2016, Takoda’s brother ran away. Police found him at a nearby Taco Bell. The boy told officers he was forced to do squats while holding a heavy backpack as punishment for misbehaving at school. Police contacted Children Services and were told a referral was made. Police attempted to search the home but couldn’t access some parts because of pit bulls.

Officers noticed cameras inside and outside the house, but McLean told them the cameras didn’t record and were only present for show. A month later, however, when McLean called police saying someone had broken into his house and threatened his family at gunpoint, McLean provided officers with video recordings from his house.

What cops knew

If there was an open abuse or neglect investigation regarding Takoda at the home, Dayton police would have no way of knowing when they arrived on the scene.

Dayton police have computer terminals in their vehicles that give them access to several databases. One is LEADS, which includes state and national criminal history records, missing persons reports, protection orders, information on stolen guns, gang information, stolen vehicle reports, immigration violators and other information. It is searched by person or object, and wouldn’t include police interactions that did not result in an arrest.

“LEADS does not included records from Children Services on abuse and neglect complaints,” wrote Lt. Craig Cvetan, public affairs commander for the Ohio Department of Public Safety, in response to questions from the Dayton Daily News.

The other database is the Ohio Law Enforcement Gateway (OHLEG). It is also searched by name, not address. And it also wouldn’t include open or prior investigations that didn’t lead to a criminal complaint or indictment.

“OHLEG would not house Children Services matters,” said Steve Irwin, spokesman for the Ohio Attorney General’s Office, which runs the program. “The only way an officer would know about potential abuse is if there is a pending criminal matter in a court or if that person had been arrested.”

Police can also access the county dispatch system, which would allow them to look up previous calls to the address. The system doesn’t flag whether there are any open or recent child abuse cases, though it does allow them to see previous reports to dispatch.

Abuse claims regarding Takoda

The first time Dayton police responded to a call regarding Takoda was May 2018 after calls from both a Dayton Public Schools worker and Children Services expressing concerns the boy was being abused. Records show no one answered the door; this was reported to children services.

Shortly after that call, Takoda was taken out of school. The next year he was signed up for homeschooling. He was never seen again by school staff.

The child endangering charges against McLean extend back to November 2018, a month where Dayton police were at the house twice and once had Takoda in the back of a cruiser.

On Nov. 14, 2018, Dayton police responded to a complaint about a fight between residents at the house about someone letting a friend park in front of the house. Police records contain no mention of Takoda.

Four days later, Hinze and McLean called police saying Takoda was being “unruly” and they wanted him taken to the Juvenile Justice Center. But after Takoda was cuffed and placed in the back seat of the cruiser, McLean changed his mind and said he would take the boy “to Kettering Hospital to get evaluated for behavioral analysis.”

Takoda was never taken to any Kettering Health Network facilities, according to hospital network spokeswoman Liz Long.

“We do not have a record of Takoda Collins ever coming to any of our facilities,” she said.

Officials from Premier Health said they need permission from Takoda’s parents or guardians before confirming whether he was ever taken to one of their facilities.

Officials from Dayton Children’s Hospital say they can’t confirm whether Takoda was treated there before he died because his final visit there involved allegations of child abuse.

Mom finds Takoda, calls police to no avail

During this time, Takoda’s mother says she had no idea where Takoda and McLean were. In 2019 she found a drunk driving arrest that told her McLean was in Dayton. She filed a contempt complaint in Wisconsin court on May 6, 2019.

“McLean has never brought Takoda to see me since he has left the state. I have spoken to him once on the phone in 4 years,” Collins wrote in the filing.

The Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office served a notice to McLean of the filing on May 8. But on May 13, the court in Wisconsin threw out the case saying if Takoda has lived in Ohio for more than six months, Wisconsin no longer has jurisdiction.

The next Day, Collins called Dayton police. The call went to Montgomery County Regional Dispatch.

“I need to speak with somebody about doing a welfare check on my son, who I believe is in danger,” Collins told a dispatcher, according to an audio recording of the call. “I don’t know how you guys do things or how it works or anything, but I believe that his father is abusing him and hurting him.”

“Continuous problems w/child’s mother, Robin Collins (redacted)” the police record says. “McLean was cooperative w/us & explained that Takoda has behavioral issues & Collins continues to makes promises to Takoda she never follow through w/. Takoda was good health.”

Dispatch records say they tried to call Collins back but there was no answer.

There’s no indication that officers spoke to Takoda alone, as Collins requested. Nor was Montgomery County Children Services notified, according to a statement from Dayton police.

Last year, Ohio became the last state in the U.S. to make police officers mandated reporters, meaning law enforcement agencies now face potential penalties for not reporting a reasonable suspicion of abuse or neglect to their county Children Services agencies.

“The officers attempted to make contact with Robin Collins, but were unable to reach her. After evaluating the information they had at the time of the call, the officers did not suspect any physical abuse, mental abuse or neglect had occurred,” Dayton police spokeswoman Cara Zinski-Neace wrote last week in response to questions from the Dayton Daily News.

Lawmaker: Let’s close these gaps

The next time Dayton police went to the home, Takoda was dying.

“My son is unresponsive right now,” McLean can be heard in a 911 call made Dec. 13.

“He’s a child with a lot of medical issues,” he says, adding that Takoda ate his own feces and played in his own urine.

Takoda was rushed to Dayton Children’s Hospital, where he died. The Montgomery County Coroners Office has not released a cause of death.

McLean is charged with rape, assault and endangering children. Hinze and her sister Jennifer Ebert are charged with endangering children as well.

State Rep. Phil Plummer, R-Butler Twp., is calling for an independent review of how this case was handled to look for possible reforms to prevent such a thing from happening again. In addition to improving oversight of Children Services —possibly including increasing public access to agency records — he said this should include reviewing how agencies communicate with each other.

“I think we’re all going to agree there are communication gaps,” he said. “So we all should sit down and see how we can close these gaps.”