RELATED: County expresses concern about region’s drinking water quality

Montgomery County purchases water from the city of Dayton’s water treatment system, and distributes it to roughly 250,000 residents of Montgomery and Greene counties. Montgomery County spokeswoman Deb Decker said the city is required to routinely monitor and update the county on PFAS levels.

PFAS are chemicals which can cause adverse health effects if ingested by people. They were first detected in the Dayton system’s drinking water over a year ago, at levels that are considered safe. County officials said they are beginning their own testing because they feel they have not received enough information from the Dayton administration on testing results or progress on preventing more PFAS from entering the region’s largest water system.

At a press conference Friday evening, Dayton Deputy City Manager Tammi Clements said the city has supplied the county with regular information about PFAS testing, which the city previously said is conducted every month.

“We’ve sent them all the reports that we have,” Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley said Saturday. The city has monitoring wells and sends testing information to the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency and the county, she said.

No one from the city could be reached Saturday to confirm when the last time testing was done.

“We just want to have more information and communication,” Lieberman said. “Our staff tells us that hasn’t been happening.”

RELATED: Progress slow in addressing chemicals in local water systems: Here’s what we found

A spokesperson for the county’s environmental services department said there are other concerns beyond PFAS.

“Dayton has been unwilling to sit down and further discuss with us more information about their water quality, or steps to address the deficits at both of their water treatment plants, well-fields, and pump station when it comes to back up power and system redundancy,” said Samantha Elder.

The county sent a letter to the Ohio EPA last week and copied the city, requesting to do its own PFAS testing.

Lieberman did not know how much the testing by the county will cost.

“We’re not saying that the water is unsafe right now,” she said. “The last time we heard numbers they were within the (safe) range.”

RELATED: 'Nearly catastrophic' break a glimpse of vulnerabilities to area's water

Whaley said the water is safe and expressed frustration about the way the county chose to raise their concerns.

PFAS are a group of man-made chemicals that can cause health problems such as developmental issues in children. They can impact fertility, interfere with hormones, cholesterol and the immune system and increase the risk of certain types of cancers.

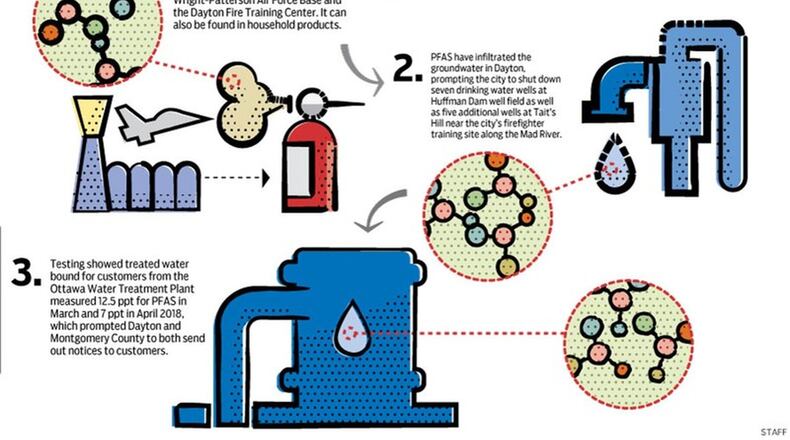

A foam commonly sprayed to put out fires is believed to be the source of PFAS in Dayton’s water. The compounds were used during training at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base and the Dayton Fire Training Center on McFadden Avenue.

PFAS are also in household products like water-repellent fabrics, nonstick products like Teflon, waxes, polishes, and some food packaging, according to the EPA.

RELATED: What you need to know about chemicals in water

Typically, the U.S. EPA sets maximum contaminant levels for the highest amount that any chemical can be present in drinking water, but that has not happened for PFAS. Instead, the federal government set a health advisory level of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) in drinking water in 2016.

The city and county sent out alerts to water customers in March and April of 2018 when PFAS were detected in trace amounts well under that limit — 12.5 parts per trillion and 7 parts per trillion. That was the first time the chemicals were detected in water bound for consumers. Prior to that the chemicals had only been detected in monitoring wells, and the Dayton water system responded by shutting down some production wells.

In March, a Dayton Daily News investigation found the city has taken some steps to ensure the safety of the water, but a lack of federal guidelines on clean-up has hindered the process here and in other cities.

The city has stopped pulling water from several wells in its Tait Hills and Huffman Dam well fields in an attempt to keep the PFAS chemicals from reaching local faucets.

The city declined to provide documentation of water quality testing levels for PFAS at the time of that investigation, but said testing is done monthly.

Following Friday’s press conference, Whaley posted on Facebook assuring Dayton water customers that the water is safe to drink.

“The City of Dayton has been transparent with our residents and customers regarding our concerns about PFAS contamination and has been aggressive in staying ahead of this issue,” she said. “In fact, we sued PFAS manufacturers earlier this year to make sure they are held accountable for any cleanup that may be necessary, and we have worked closely with the federal EPA to advocate for even more aggressive water quality standards for PFAS than currently exist.”

RELATED: Dayton lawsuit seeks damages from makers of firefighting foam

That lawsuit was filed in October and named 3M Company, Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co., Buckeye Fire Equipment Company, Chemguard Inc., Tyco Fire Products L.P., and National Foam Inc. The city hired Paul Napoli, a New York lawyer who has filed similar lawsuits across the country.

It seeks to recover past and future damages for the remediation of PFAS, which Napoli told the Dayton Daily News in November could run as high as $20 million per well. The city has more than 180 wells.

Lieberman said Saturday the county plans to join the city in that lawsuit.

Last year the city and county signed a 20-year agreement establishing a long-term commitment by the county to continue purchasing the city’s water.

INVESTIGATION: Partial pipe replacements may be tainting drinking water

The PFAS contamination concerns have come on top of two recent incidents in which the city’s water plant lost power or pressure, causing county-wide water boil advisories. One hit in February and was caused by the collapse of a major water main. The second occurred on Memorial Day because of power outages caused by the tornadoes that swept through the region that night. The loss of pressure prompted a boil advisory for customers that lasted four days.

In April, U.S. Rep. Mike Turner, R-Dayton, convened a group of local community leaders to evaluate the safety of Dayton’s water supply in response to outage that took place in February. Both Lieberman and Dayton City Manager Shelley Dickstein are on that board which is exploring hiring a national, independent consultant to study the water system.

Lieberman said they did not discuss the PFAS communication issue at the group’s initial meeting.

INVESTIGATION: Aging water infrastructure could cost rate payers billions of dollars

“If you consider we’ve had two major water problems in a three-month time frame and we have had no PFAS testing results, I think you can understand the concern,” said Deb Decker, assistant director of communications for the county.

County Administrator Michael Colbert and Environmental Services Director Pat Turnbull plan to hold a press conference on the matter Monday morning at 10 a.m.

ABOUT THE PATH FORWARD

Like all of you, we care deeply about our community, and want it to be the best it can be. Last year, we formed a team to dig into the most pressing issues facing the Miami Valley. The Path Forward project, with your help and that of a 16-member community advisory board, seeks solutions to issues readers told us they were most concerned about. That includes investigating the security and sustainability of our drinking water, one of our region’s most critical assets.